The Better Radio Experiences project has now ended, so I'm wrapping it up with a post on what we produced and what we expect to happen next.

Better Radio Experiences was a project to expand our ideas of what radio might become. The point was not to build products to use right now, but to map some of the territory of potentially thousands of new radio and sound-related applications that could exist.

As Kate has described, we started by undertaking in-depth research about the lives of a small number of young people in order to understand the role of sound in their lives. We built five prototypes to address some of their high-level needs using technologies made in R&D. We made a further four prototypes in a two-day hack event with our colleagues.

We wanted to select some good paths through the new territory. We did this by asking people to tell us what they thought of our ideas by showing them physical objects representing new features.

This last part needs a bit more explanation.

A frustration for designers is that if you show an app to someone to get their opinion and it looks like it's finished, they will critique the appearance and not the functionality. In this particular project, we were not interested in whether a button on a screen should be a certain colour, but whether the underlying feature is worth putting more time and effort into.

We wanted to explore the finding that a typical experience of listening to music for our group was to keep one large playlist on their phone and skip the songs they didn't want to listen to right now as they came up. The idea of skipping parts of audio in an Object-Based Media world is a very rich one - you could skip songs, but also topics, segments of shows or particular people speaking. Or all speaking but keep the music. Or everything above a certain tempo. And so on.

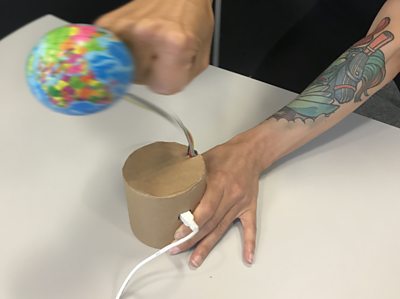

So, we made the Everything Avoider.

To avoid something, you (gently) punch the ball at the top. A robot voice explains what it's doing and the next track (or segment) plays.

Making a physical device like the Everything Avoider serves three distinct purposes.

Firstly, instead of inviting comments on the colour of "avoid" button, it abstracts up a level, to invite comments about how we might use it and whether we would. It does this by being very obviously a prototype (made of cardboard) and by refusing to even consider the question of button-colour, because it's not on a screen.

Secondly, it makes people want to explore and use it. It's fun to play with and does something interesting. Fun things give us better feedback. People are more interested. Their responses are more authentic.

Finally, because it only has one thing you can do with it, it made us think hard about how to make it obvious what's possible (skipping parts of the audio), how to make it simple to use (punch the ball), and how to make it useful (deciding what should be skipped). It made us think in-depth about the feature we wanted to describe.

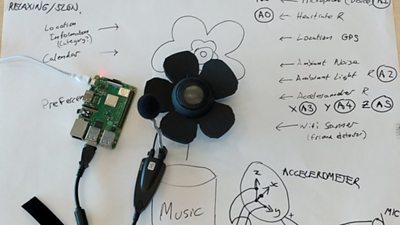

Many of these advantages of having a physical device can also be achieved using "design fictions", objects that represent a feature but don't do anything. Making a working device also pushed us to extend the technology that could make this real one day. We used technology from R&D - in this case from the Content Analysis Toolkit (transcription and segmentation), and researched machine-generated continuity announcements for personalised continuous streams of audio. To quickly make the prototypes themselves, we developed an which runs on a and uses .

- Â鶹ԼÅÄ R&D - Unexpected Ideas by Bringing User Research To Life

- Â鶹ԼÅÄ R&D - What Do Young People Want From a Radio Player?

Here are the other prototypes we made, each with a few notes about why we made it.

The Enloudinator is the first prototype we built. The young people we spoke to talked about the importance of being able to hear the different parts of the music, to increase the music's resonance with their feelings.

"I think the most important part of music for me is quality, really, because I have to be able to hear exactly what’s going on in the song so that I can attach my emotions to it or attach my mood to it."

The Enloudinator increases the audio volume when the background noise increases, using the WebAudio API and work from the Audio Research team in R&D. The "sail" on top gives an indication of how loud the background noise is.

The young people in our study frequently mentioned wanting to hear and understand a specific component of the music, the lyrics.

"I think lyrics are equally as important to the actual tune of the song itself."

"Always, when I listen to music, I subconsciously tend to learn the lyrics and I like listening to the lyrics to figure out, kind of, what a song means or whatever, because I feel like I enjoy it more if I know what the person's talking about, rather than just listening to music."

Emoji Parade addresses this by translating the lyrics to emojis and displaying them on a small screen, synchronising them with the music.

The Peeps prototype was inspired by the observation that the young people we spoke with were interested in artists' lives as well as their music, at least for certain artists, such as the "Lil' Peeps" - a loose grouping of artists posting heavily on social media, Soundcloud and YouTube.

For those interested in groups of artists like these, we developed an application that collects all the social media it can find for a select group, until it's "full" and then can be turned over to play a personalised, auto-generated collection of robotically-voiced posts and music.

Finally for this first round, we used some of the audio from the Cook-Along Kitchen Experience (CAKE) project in order to experiment with the idea of broadcast as an addition to "my music".

Although our participants sometimes listened to radio, they much preferred their own music:

"...the radio it’s a bit hit-and-miss really, because if you don’t like the song that’s come on, you can’t skip it and then you’re there, sort of, forever changing between stations to try and find a song that you want, whereas on your playlist you know you’re going to potentially like all the songs that come on it."

In Radio-CAKE, a programme with time-dependent components (like making a recipe) or with time-dependent social components (like keeping in touch with the news) breaks through into my music at the appropriate time. "My music" becomes the default sound but broadcast audio appears intermittently as needed.

Hack event

Andrew and Dan developed the software side of the these prototypes, while also building and documenting an to enable others to make similar experiences easily, by using the .

The hack event we held with colleagues in the Â鶹ԼÅÄ surprised us by its success; veterans of a few hackdays ourselves, we did not expect four working physical prototypes to come out of a two-day event. A big part of that success was the work Dan and Andrew put into making the software and , and designing it to support tinkering-based development: you can write some code, copy/paste it onto the device, and easily poke around with the Web Inspector to see what's happening. Another huge part was the expertise we had available in electronics and design (from ) and cardboard prototyping (from ).

Throughout the two days, Kate's focus on the user research meant we never lost touch with the needs of the young people we had spoken to.

Here are the four prototypes made at the event.

Soundtrack to my life was inspired by comments from the young people we spoke to about hating silence:

"I like having background noise. I can’t sit in silence. I find it awkward. It’s horrible.... at work, it kind of makes us go slower, and just music, or someone talking, or anything, helps the time go by a little bit."

Soundtrack to my life is a wearable device that plays music according to your geographical position, the speed you are moving at and your heart rate, finding a piece of music that suits you right now.

The young people we talked to frequently used music to manage or medicate their mood.

"I would go on the [Spotify] app, and then I’d play a song and test it, and be like, 'Is this making me feel like I want to feel?' If not, I will pick something a bit different."

"Because I’m in a bad mood as I’ve just had a massive, petty argument with my Mum and Dad... Definitely, it's calming me down and distracting me from how angry I am."

Moodulator addresses that need by allowing you to find music to modulate your mood by turning a dial. Mood is identifiable by colour, happy (red) to sad (blue). It then then plays a stream of related music.

The participants in our research told us how vividly music and sound summoned memories of people and events, and how important these memories were to them.

"[This music] makes me feel so, so happy because I have amazing memories linked with this song."

"I have this really weird thing with whenever I listen to songs that I haven’t listened to in months and months, when I listen to it, I’ll think of that time when I was listening to it, so I find that really strange."

Two prototypes addressed this need in different ways. Gignmix is a multi-part device that allows friends to control the components of a music track together, re-experiencing the memory of having heard it at a gig.

Object Based Media is a store of your memories related to objects - for example gig tickets, tshirts, or in this case, a candle, a set of panpipes and a cap. When the object is lifted off the platform, it plays the music or sound associated with it.

Evaluation

We demonstrated eight of the nine prototypes with sixteen 15-year-old pupils at , who gave us definite steers about the direction of the work. For example, Emoji Parade, a prototype I'm very fond of, was seen as being childish - they would prefer to see the real lyrics. Peeps was seen as superfluous for music ("you'd just look on social media") but might be useful for sport or news.

The initially surprising overall result of the evaluation was that the hack event prototypes were much more enthusiastically received than the others. We attribute this to the careful attention to user needs, design, and functionality during the two days, coupled with the enthusiasm and commitment of our colleagues.

What next?

Our plan is to describe the map of radio and sound possibilities we've been making, and explore it further ourselves. We have made and opened up the . There is lots more to explore, which we're going to do by working with artists and more directly with young people.

We would like to develop our further. It's a very powerful tool, because it combines the ease of use, large talent pool and huge number of libraries (Javascript / HTML), with a powerful, cheap and flexible device, and large community of the Raspberry Pi.

Finally, we think that we have invented a new process, as exemplified by our manifesto below, which we plan to document further and apply to different domains.

BRE Manifesto

First, we start with people - using in-depth interviews, diary studies and workshops first to try and work out what people are really trying to do when they listen to the radio or music. We're using their experiences as a springboard for ideas. We always have a voice on the team for those users as we develop prototypes.

Second, we make things. Ideas are cheap, but figuring out what to build is hard. Ideas embodied as physical objects give us the best, most engaged evidence about which to work with further and which to discard.

Third, we evaluate many ideas. Whole branches of potential might be curtailed if we polish our ideas too soon and bet on one branch.

Fourth, we get different opinions. Showing the results to people like ourselves doesn't tell us anything we don't already know.

Photo credits: Joanna Rusznica / Andrew Wood / David Man; Vicky Barlow

-

Internet Research and Future Services section

The Internet Research and Future Services section is an interdisciplinary team of researchers, technologists, designers, and data scientists who carry out original research to solve problems for the Â鶹ԼÅÄ. Our work focuses on the intersection of audience needs and public service values, with digital media and machine learning. We develop research insights, prototypes and systems using experimental approaches and emerging technologies.