Sheku Kanneh-Mason and Isata Kanneh-Mason

Sunday 6 September, 5.30pm–c7.00pm

(Βι¶ΉΤΌΕΔ Radio 3)

Friday 11 September, 8.00pm–c9.30pm

(Βι¶ΉΤΌΕΔ Four)

Ludwig van Beethoven

Cello Sonata No. 4 in C major, Op. 102 No. 1 15’

Samuel Barber

Cello Sonata, Op. 6 20’

Frank Bridge

Mélodie 5’

Sergey Rachmaninov

Cello Sonata in G minor, Op. 19 35’

Sheku Kanneh-Mason cello

Isata Kanneh-Mason piano

This concert is broadcast on Βι¶ΉΤΌΕΔ Radio 3 on Sunday 6 September at 5.30pm and on Βι¶ΉΤΌΕΔ Four on Friday 11 September at 8.00pm. You can listen to any of the 2020 Proms concerts on Βι¶ΉΤΌΕΔ Sounds or watch on Βι¶ΉΤΌΕΔ iPlayer until Monday 12 October.

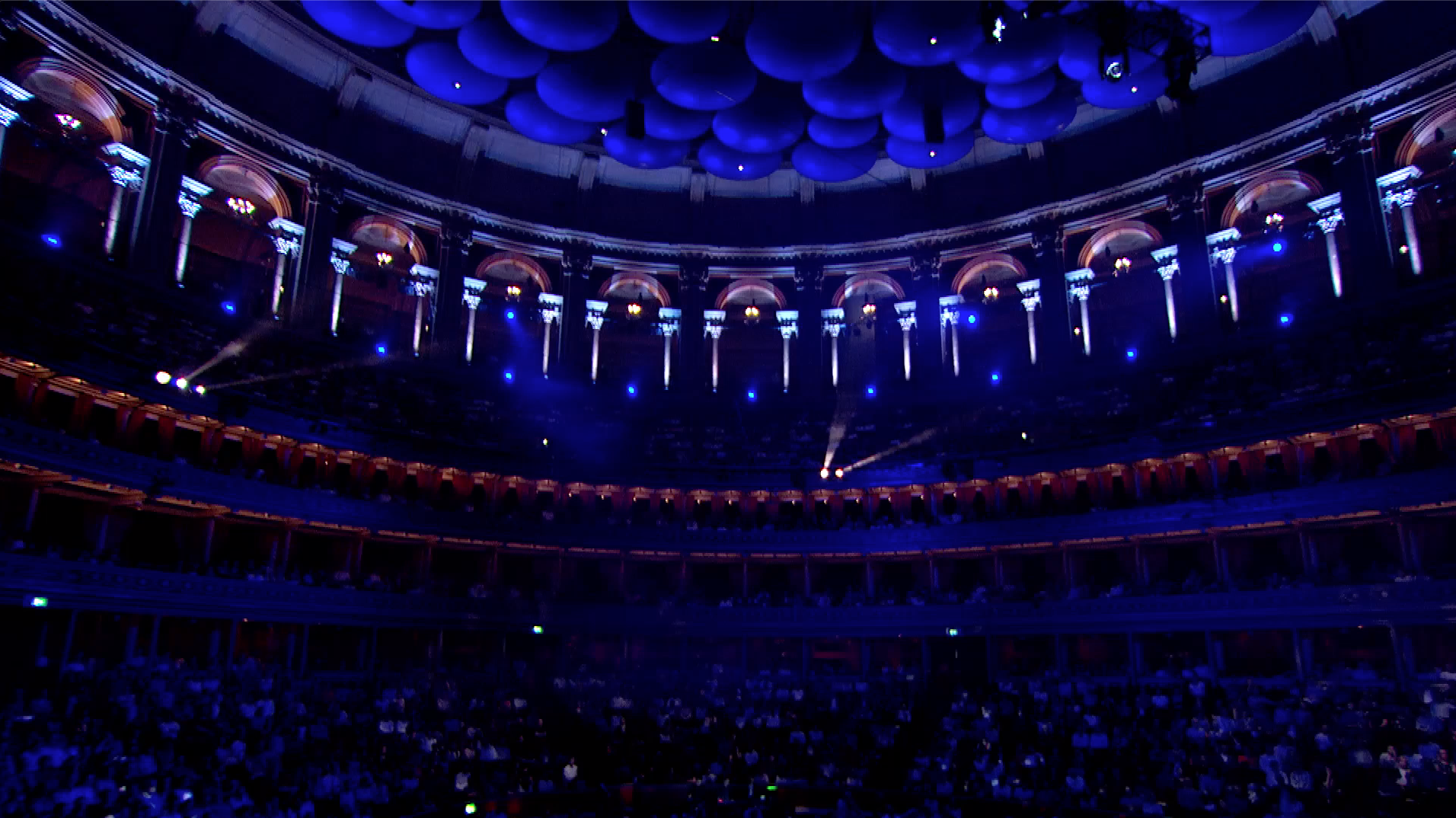

Welcome to today’s Prom

At only 21, cellist Sheku Kanneh-Mason is already sought-after internationally, having won Βι¶ΉΤΌΕΔ Young Musician in 2016 and performed two years later to a worldwide audience of over 35 million at the wedding of Prince Harry and Megan Markle.

For this specially pre-recorded Proms recital he is joined by 24-year-old Isata Kanneh-Mason, the eldest of the family’s seven musical siblings, who released her first solo CD last year to great acclaim.

Continuing our 250th-anniversary celebrations of Beethoven’s birth, his C major Cello Sonata reflects the concentration of expression and form typical of his late period. By contrast, Barber’s sonata, though written in 1932, looks backwards, its drama and lyricism rooted in the Romantic era.

After Bridge’s passionate, youthful and lightly Impressionistic Mélodie comes Rachmaninov’s post-Romantic sonata, a full-blooded cornerstone of the cello/piano repertoire whose macabre scherzo movement and joyously ebullient finale contrast with a slow movement of melting bittersweet indulgence.

Welcome to today’s Prom

At only 21, cellist Sheku Kanneh-Mason is already sought-after internationally, having won Βι¶ΉΤΌΕΔ Young Musician in 2016 and performed two years later to a worldwide audience of over 35 million at the wedding of Prince Harry and Megan Markle.

For this specially pre-recorded Proms recital he is joined by 24-year-old Isata Kanneh-Mason, the eldest of the family’s seven musical siblings, who released her first solo CD last year to great acclaim.

Continuing our 250th-anniversary celebrations of Beethoven’s birth, his C major Cello Sonata reflects the concentration of expression and form typical of his late period. By contrast, Barber’s sonata, though written in 1932, looks backwards, its drama and lyricism rooted in the Romantic era.

After Bridge’s passionate, youthful and lightly Impressionistic Mélodie comes Rachmaninov’s post-Romantic sonata, a full-blooded cornerstone of the cello/piano repertoire whose macabre scherzo movement and joyously ebullient finale contrast with a slow movement of melting bittersweet indulgence.

Ludwig van Beethoven (1770–1827)

Cello Sonata No. 4 in C major,

Op. 102 No. 1

(1815)

1 Andante –

Allegro vivace

2 Adagio – Tempo d’Andante –

Allegro vivace

Beethoven wrote two cello sonatas in 1815, both with the opus number 102. They could hardly be more different. Op. 102 No. 2 is a classic Beethoven journey from light, down into inkiest darkness, returning tentatively, then resolutely to light at the end. Op. 102 No. 1, however, is much more playful, quirky, teasing, like the Beethoven we sometimes meet in letters to his closest friends – Beethoven the verbal prankster, the lover of excruciating puns. And, while Op. 102 No. 2 is clearly divided into three weighty movements, No. 1 is much more fluid, at times seeming to delight in defying our expectations.

The opening Andante is a close, affectionate conversation between the cello and the piano. After a climactic flourish for the piano it comes to a pause – but we’ve hardly time to get used to this before the second section, marked Allegro vivace, springs off like a greyhound released from the trap. This sounds a lot more like the passionate, stormy Beethoven of legend, but it’s striking how carefully Beethoven balances the two instruments so that the much more powerful piano never overwhelms the cello.

At home with the Kanneh-Masons: the seven-sibling supergroup (with pianist Isata and cellist Sheku furthest right) captured for the Βι¶ΉΤΌΕΔ’s imagine… arts series, broadcast in July (Swan Films/Βι¶ΉΤΌΕΔ)

The Kanneh-Masons at home (with pianist Isata and cellist Sheku furthest right) (Swan Films/Βι¶ΉΤΌΕΔ)

At first the Adagio that follows seems to promise a profound slow meditation, but it isn’t long before the theme of the first movement drifts back in on the piano as though nothing had happened since we last heard it. This also comes to a pause, then piano and cello play with a tiny four-note rising figure, as though they were trying it out. Another Allegro vivace, the finale, grows from this, but this one is wonderfully upbeat and full of subversive fun – at a couple of points the cello softly imitates bagpipe drones while the piano snaps at it impatiently. But at the very end the two instruments are splendidly, joyously united.

Samuel Barber (1910–81)

Cello Sonata, Op. 6

(1932)

First performance at the Proms

1 Allegro ma non troppo

2 Adagio

3 Allegro appassionato

The American composer Samuel Barber was just 22 when he wrote his Cello Sonata, at which time he was still a student at the Curtis Institute of Music in Philadelphia. Barber himself gave the premiere in 1933 (he was a fine pianist) with his friend Orlando Cole playing the cello. It was a huge success, winning Barber both a Pulitzer Travel Stipend and a Prize from the American Academy in Rome, which enabled him to study for a year at the Academy. It was during that important formative year that he composed what was to become his famous Adagio for Strings.

Something of that Adagio’s deep melancholy can be heard in the Cello Sonata too, but here there are much wider contrasts, stylistically and emotionally. Barber studied Brahms’s two classic cello sonatas thoroughly before writing his own, and there are echoes of these in Barber’s sonata. He also worked closely with Orlando Cole to make sure his ideas were really suited to the cello. But, for all Brahms’s and Cole’s input, the result is pure Barber, in its sustained, warmly expressive melodic writing, and in the way the sonata balances ripe, impassioned late-Romanticism with an utterly 20th-century attitude to rhythm – especially in the last of the three movements, where rapid switches in metre (the number of beats to a bar) constantly throw the listener off balance. (Try counting along and you’ll soon get lost.)

The central movement also springs a surprise in the way it morphs from slow lyricism to a quick-fire Presto and then back again. At every stage, though, Barber remembers that this is a sonata for cello and piano: lively or passionate dialogue between the instruments is as important here as in the duo sonatas of Beethoven’s time.

Frank Bridge (1879–1941)

Mélodie

(1911)

First performance at the Proms

Frank Bridge first came to maturity in Edwardian England, when the big name in British music was Edward Elgar. But Elgarian imperial ‘Pomp and Circumstance’ did not appeal to this sensitive, troubled man. The First World War horrified him and in later years he turned to Continental modernist figures such as Alban Berg to provide him with a language to express his intense pacifist feelings. The Mélodie for cello (or violin) and piano was written in 1911, when Bridge was still very much a Romantic at heart, but it shows his remarkable ability to condense strong, ardent feeling into a short, elegantly shaped musical span. Bridge was a fine string-player, as you can probably tell from the way he brings out the cello’s expressive power and tender delicacy.

Sergey Rachmaninov (1873–1943)

Cello Sonata in G minor, Op. 19

(1901)

1 Lento – Allegro moderato

2 Allegro scherzando

3 Andante

4 Allegro mosso

A religious procession in front of the Cathedral of the Assumption in Moscow’s Kremlin, c1901 – around the time Rachmaninov composed his Cello Sonata (Granger/Bridgeman Images)

The Cathedral of the Assumption in Moscow’s Kremlin, c1901 – around the time Rachmaninov composed his Cello Sonata (Granger/Bridgeman Images)

In 1897 the 23-year-old Rachmaninov suffered one of the most catastrophic humiliations ever endured by a composer of genius. The first performance of his audacious First Symphony went badly enough in itself; then, to cap it all, the critics were merciless. Shattered by the experience, Rachmaninov was unable to compose for three years. But then someone had the idea of sending him to a noted (and very musical) hypnotherapist, Dr Nikolay Dahl. The treatment worked: by the summer of 1901 Rachmaninov was able to complete what was to become one of his most popular works, the Second Piano Concerto. Soon afterwards, he was at work on another major piece, his Cello Sonata. The piano concerto was such a success that it completely eclipsed the cello sonata (so often the fate of chamber works), but the sonata is a wonderful work in its own right, recalling the concerto in the sweep of its melodies and in the brilliance of its writing – particularly for Rachmaninov’s own instrument, the piano.

Still, this is very much a duo sonata, which partly reflects Rachmaninov’s own close relationship with the cellist for whom he wrote it, the outstandingly gifted player Anatoly Brandukov. Although Brandukov was significantly older than the composer, the two became such close friends (they often gave concerts together) that Rachmaninov chose him as his best man at his wedding the following year.

It’s clear from this sonata that Rachmaninov paid close attention when Brandukov was playing. Throughout the four movements the piano often presents the themes first, with the cello picking them up and elaborating on them, yet the cello always changes the character of the music when it takes up the leading ideas, and there’s no question of the pianist being the ‘star’. After this, Rachmaninov wrote no more chamber music. It’s hard to complain when you consider what he did go on to create – not least, two more piano concertos, the Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini for piano and orchestra, and the orchestral Symphonic Dances – yet this Cello Sonata remains a fascinating pointer to a path not taken.

Programme notes © Stephen Johnson Stephen Johnson is the author of books on Bruckner, Mahler, Shostakovich and Wagner, and a regular contributor to ‘Βι¶ΉΤΌΕΔ Music Magazine’. For 14 years he was a presenter of Βι¶ΉΤΌΕΔ Radio 3’s ‘Discovering Music’. He now works both as a freelance writer and as a composer.

Biographies

Sheku Kanneh-Mason cello

Sheku Kanneh-Mason (Jake Turney)

Sheku Kanneh-Mason (Jake Turney)

Winner of the 2016 Βι¶ΉΤΌΕΔ Young Musician competition, Sheku Kanneh-Mason became a household name in May 2018 after performing at the wedding of the Duke and Duchess of Sussex at Windsor Castle.

He began learning the cello aged 6 before entering the Junior Department of the Royal Academy of Music, where he currently studies full-time with Hannah Roberts. He has also worked in masterclasses with Alexander Baillie, Guy Johnston, Julian Lloyd Webber, Miklós Perényi and Rafael Wallfisch.

He has appeared with the Atlanta, Baltimore, Frankfurt Radio and Seattle Symphony orchestras, the Βι¶ΉΤΌΕΔ, Japan, London and Royal Philharmonic orchestras and the Netherlands Chamber Orchestra. Current plans include performances with the Βι¶ΉΤΌΕΔ, Βι¶ΉΤΌΕΔ Scottish, City of Birmingham and Toronto Symphony orchestras.

A keen chamber musician, he performs with his pianist sister Isata and violinist brother Braimah as a member of the Kanneh-Mason Trio. In recital he has appeared across Europe and on a tour of North America, including his Carnegie Hall debut.

During the Covid-19 lockdown, he and his siblings gave live-streamed performances from their family home in Nottingham and appeared on an edition of the Βι¶ΉΤΌΕΔ’s imagine... documentary series.

His second album, featuring Elgar’s Cello Concerto with the London Symphony Orchestra under Sir Simon Rattle, was released in January, reaching No. 8 in the UK Official Album Chart. This made him the youngest classical instrumentalist, and the first cellist, ever to reach the Top 10.

Sheku Kanneh-Mason is an ambassador for JDFR – the children’s Type 1 diabetes charity – as for London Music Masters and Future Talent, and was appointed MBE in this year’s New Year Honours list.

Isata Kanneh-Mason piano

Proms Debut Artist

Isata Kanneh-Mason (Robin Clewley)

Isata Kanneh-Mason (Robin Clewley)

Isata Kanneh-Mason reached the Keyboard final of the 2014 Βι¶ΉΤΌΕΔ Young Musician competition and went on to study as an Elton John Scholar at the Royal Academy of Music, performing with Sir Elton in 2013 in Los Angeles. She has since embarked on a busy career, giving concerto appearances, solo recitals and chamber concerts throughout the UK and abroad.

She also continues to perform with her siblings, including regular duo recitals with her cellist brother Sheku. Together, they have recently appeared across Europe and in a 10-city US tour. In recital she has appeared in the Portland Piano Series, Oregon, the Barbican Centre’s Sound Unbound festival, the Colour of Music festival in South Carolina, at the Bath, Cheltenham and Edinburgh festivals, Snape Proms, Musikfestspiele Saar (Saarland, Germany), and in venues from Antigua and the Cayman Islands to Perth (Scotland).

Her debut album, Romance, featuring works by Clara Schumann in the composer’s 200th-anniversary year, was released last July to widespread acclaim, reaching No. 1 in the UK Classical Album Chart.

Isata’s lockdown performance of the first movement of Beethoven’s Piano Concerto No. 3, accompanied by a chamber ensemble comprising her siblings, received over one million views online.

Future projects include concertos with the Gothenburg Symphony, Hallé, Johannesburg and KwaZulu Natal Philharmonic orchestras and Sarasota Orchestra. Next season she is Young Artist in Residence with the Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra.

We hope you enjoyed tonight’s performance

For full details of Βι¶ΉΤΌΕΔ Proms 2020 concerts and broadcasts, visit bbc.co.uk/proms

Online programme produced by Βι¶ΉΤΌΕΔ Proms Publications