Chard, Somerset: The Only VAD Amputee Hospital

Prejudice attitudes towards disfigured servicemen

Images of wounded and disabled servicemen and women are commonplace today. A modern twenty-hour hour media industry with its fascination for human angles and personal stories almost guarantees coverage of those who have been injured in the line of duty.

But during World War One public attitudes could not have been more different. Then the mere thought of badly maimed and disfigured men returning from the battlefields was abhorrent to many people. The sight of soldiers, sailors and airmen with limbs missing due to injury or amputation was a shock; it wasn’t unusual for people to cross the road to avoid passing a so-called ‘invalid’ or for parents to shield their children’s eyes.

At the start of the war there was also a shortage of artificial limbs (prostheses), a woefully small number of trained surgical fitters and virtually no programme of rehabilitation for limbless servicemen. Whether through oversight, shame, embarrassment or prejudice; the neglect and exclusion of the most severely injured was an unpalatable truth of war.

It would be heartening to think that the establishment of the only specialist VAD (Voluntary Aid Detachment) hospital to care for and rehabilitate amputees was an act of benevolence from the War Office or a gesture of gratitude from the armed services. However, the truth lies not in officialdom but in the dedication of volunteer nurses and an accident of geography.

Monmouth House, a Georgian building which today makes up part of Chard School, became a VAD hospital in 1915. Nearby, off Chard High Street, were the premises of a remarkable and innovative man called James Gillingham and his son, Sydney.

Gillingham Senior had turned his family boot-making business in to one which produced bespoke artificial limbs. The transformation from footwear to prosthetics came about after an unfortunate accident at the town’s celebrations of the wedding of the Prince of Wales (later King Edward VII) to Princess Alexandra of Denmark in 1863. A gamekeeper called William Singleton had been loading a cannon when it was fired prematurely. Singleton’s right arm was so badly damaged it had to be taken off at the shoulder and when he was told that it was impossible to attach an artificial limb to the stump, Gillingham offered to make him one for free.

Fifty-two years later, this public spirit and generosity would appear to be the driving force behind the establishment of the amputee hospital.

The surroundings for the patients were in complete contrast to the deafening noise and insufferable mud of the Western Front. The main school building next door was a sixteenth century town house and became a Grammar School in 1671. The men were looked after in a two-storey annex to Monmouth House known as the ‘ballroom’ and built sometime before the war began. It had French windows and a glass conservatory where handrails had been fitted and pace-lengths marked on the floor.

In an era when most artificial limbs were ‘off the shelf’ and made of wood, Chard was a place of relative indulgence. Each limb was made to order using moulded leather, they were expertly fitted by the Gillinghams and then each patient was shown how to make the best use of their new arm, leg or hand.

By the end of the war; 1, 051 men had been fitted with new limbs and trained to use them at Monmouth House.

In the 1920s the building became part of Chard School which today is an independent day school and nursery. It’s run by staff and governors who know and cherish the school’s long and eventful history. It’s thanks to them that the story of the World War One amputee hospital, and the men whose lives it changed, will never be forgotten.

Location: Chard School, Fore Street, Chard, Somerset TA20 1QA

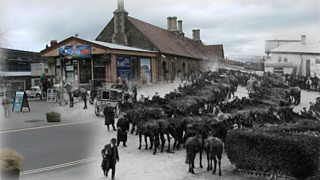

Image: VAD nurses and patients, courtesy of Chard Museum

Duration:

This clip is from

Featured in...

![]()

Â鶹ԼÅÄ Somerset—World War One At Â鶹ԼÅÄ

Places in Somerset that tell a story of World War One

More clips from World War One At Â鶹ԼÅÄ

-

![]()

The loss of HMY Iolaire

Duration: 18:52

-

![]()

Scotland, Slamannan and the Argylls

Duration: 07:55

-

![]()

Scotland Museum of Edinburgh mourning dress

Duration: 06:17

-

![]()

Scotland Montrose 'GI Brides'

Duration: 06:41