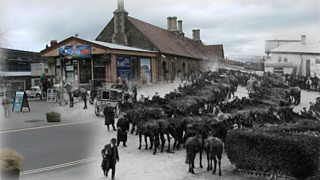

Taunton, Somerset: The Christmas Truce

The significance of the Christmas truce for Somerset

The singing, the handshakes, and the worldβs most unlikely football match; many people know what happened during the Christmas truce on the Western Front in December 1914. Well despite the legend which surrounds the event, there is a darker side to the day, which is often overlooked.

Earlier in the month Pope Benedict XV had suggested that fighting should officially cease as a way of marking Christmas. However his plea fell on deaf ears as the warring nations refused to stop hostilities. But in battle what the Generals want may not always be the desire of the private soldier; and so it was on the first Christmas Eve of the war. Itβs well chronicled that troops in the British trenches heard the enemy singing across the lines and returned the compliment with their own Christmas carols. The next day, after persuasion by the Germans and a great deal of hesitation, Tommies at certain points ventured in to no manβs land. Unarmed and filled with a spirit of goodwill, they greeted each other, shared cigarettes and swapped small gifts.

A century on, debate still rages about where the fabled football match took place or if, in fact, there was more than one game played between the lines that extraordinary Christmas Day. But whatever the details; the fact that a match took place that day means it has become part of our national folklore.

Less well known is a more sombre act which took place between men who had been mortal enemies just hours before; the retrieval and exchange of the bodies of fallen comrades.

Among those whose remains were returned to the British trenches was Captain Charles Carus Maud DSO of βBβ Company of the Somerset Light Infantry. The Sudan and Boer War veteran had been killed six days earlier as he led his men on an attack on a section of the German line β nicknamed he Birdcage β on account of the amount of barbed wire surrounding it. He was killed by a bullet to the stomach and died where he fell.

The curator of the Somerset Military Museum, Mike Motum, says Maud was an impressive soldier: βHe was pretty physically fit, single minded, able to manage men, make tough decisions and when the chips were down he could leadβ.

As his body was handed over to his regiment, a German officer who had witnessed the action remarked that Maud had been βthe bravest of the braveβ. Shortly afterwards he was buried and the simple temporary wooden cross which marked his grave eventually came home with the Somersets. Today it has pride of place in the Somerset Military Museum at Taunton Castle.

Wellington-based author, Suzie Grogan, has studied death, grieving and trauma in World War One in her book βShell Shocked Britainβ. She says the return of Maudβs remains would have been a pivotal moment: βFor families at home, to find the body of a loved one was critical for the mourning process. In modern terminology we would call it closure. For the men he commanded, retrieving him and giving him a decent burial would have helped restore order and disciplineβ.

Charles Maud was far from being the only fallen soldier to be returned to his comrades on 25 December 1914. But his story and the grave marker which bears his name ensure that future generations will forever be aware that the famous Christmas truce was about more than just some βfagsβ and a football match.

Location: Somerset Military Museum, Museum of Somerset, Taunton Castle, Castle Green, Taunton TA1 4AA

Image: Captain Charles Maud in 1913, courtesy of the Somerset Military Museum Trust

Duration:

This clip is from

Featured in...

![]()

ΒιΆΉΤΌΕΔ Somerset—World War One At ΒιΆΉΤΌΕΔ

Places in Somerset that tell a story of World War One

![]()

Memory—World War One At ΒιΆΉΤΌΕΔ

Memorials and the commemoration of wartime lives

More clips from World War One At ΒιΆΉΤΌΕΔ

-

![]()

The loss of HMY Iolaire

Duration: 18:52

-

![]()

Scotland, Slamannan and the Argylls

Duration: 07:55

-

![]()

Scotland Museum of Edinburgh mourning dress

Duration: 06:17

-

![]()

Scotland Montrose 'GI Brides'

Duration: 06:41