Swindon, Wiltshire: Hospital Trains

The mind behind innovative medical trains made in Swindon

Frank Marillier is a name passed over by history. But his contribution to the war effort earned him the thanks of the nation, and the suggestion that his work helped bring the war to an earlier end.

Sandra Gittins is the author of βThe Great Western Railway in the First World Warβ. She says that the idea of using trains to transport wounded back from the front was first thought of in the South African War (1899-1902). With the prospect of a European war looming, the suggestion surfaced again.

The Government circulated plans to the countryβs railway companies, Great Western Railway (GWR) among them, asking if they would be able to build ambulance trains, if needed. The trains would be used in Britain, transporting casualties back from the coastal ports, or in France bring them back from the front to the channel ports.

The answer was βyesβ, and so by August 1914, orders for 12 trains had been placed with the railway companies. Initially, two were built by GWR at its works in Swindon.

The ambulance trains were actually converted carriages, with much of the necessary conversion work at GWR falling to the carriage works department. Its manager was Frank Marillier. A Bristol man by birth, heβd moved to Swindon in 1876, where he was first appointed as a draughtsman.

As war progressed, he also became chair of the βSub Committee for Ambulance Trains for the Continentβ. It was this group which decided on what features should be included in the ambulance trains.

It became clear to Frank Marillier that the original plans for beds in the carriages could be improved, both in terms of comfort of the patients and the number which could be carried.

βWhen the ambulance trains were first designed, they did come across one problemβ, says Sandra. βMost of them were designed for sitting cases. That was a problem with long distances. Say a ship docked at Dover or Southampton and was taking casualties to, say Liverpool; that was a long journey. The patients couldnβt remain seated all that time but to have patients lying down all the time was a potential waste of space.β

Frank Marillierβs committee came up with an ingenious, yet simple solution.

Instead of two cots on each wall of a carriage, he put up three cots. Whilst this sounds like it would make conditions more cramped and uncomfortable, what it actually did was to create greater flexibility for patients and increased comfort too.

The uppermost cot would always be for a lying patient but the mid and lower cot could be used to accommodate sitting patients. The mid cot would be swung down to meet the lower, forming a backrest against which to relax.

The mid cot could always be swung up for a lying patient, with another below on the lower cot. With the change in configuration taking a matter of minutes, medical staff could respond quickly to the changing needs of individuals, or a new intake of patients.

Sandra says the system was a breakthrough: βIt could be converted from three layers of lying patients to one layer above and the bottom tier to seated soldiers. It gave flexibility, meaning that people could lie down when they wanted, or sit down. On a normal carriage, you could only have seated patients, or lying down patients. It also meant that you could carry a third more patients on one carriage than you could normally.β

The innovations did not end there. The cot system provided for stretchers being placed directly on them, which saved soldiers a possibly painful transition from stretcher to bed.

Frank Marillier received formal recognition for his efforts with an OBE and a CBE.

A letter from the War Office in 1920 thanked the Sub Committee for Ambulance Trains for the Continent, saying that its work βundoubtedly helped in a marked degree towards the successful termination of the late warβ.

Edwardian verbosity aside, the Government of the day evidently looked upon the work of the committee, led by Frank Marillier, as having made a significant contribution to ending the war.

βThis was no small thing to sayβ, agrees Sandra. βThey obviously thought the work of Frankβs committee to be very important to the war effort, as it was.β

By warβs end, the GWR had built 12 ambulance trains but the companyβs contribution extended beyond that. Elaine Arthurs is one of the curators at STEAM, the Museum of the Great Western Railway, on the site of the former works in Swindon. βThe kind of work they did was incredible reallyβ, she says. βThe GWR had the right staff, skills and workforce to manufacture military vehicles, carriages, guns and general munitions.β

As for Frank Marillier, he retired from the GWR in 1920. He died on 14 June 1928, aged 72.

Location: STEAM: Museums of the GWR (former site of the GWR works), Fire Fly Ave, Swindon SN2 2EY

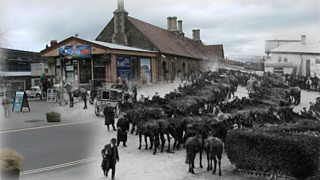

Image shows Frank Marillierβs committeeβs triple bed design, which increased patient capacity on ambulance trains. Photograph courtesy of STEAM: Museum of the GWR

Duration:

This clip is from

Featured in...

![]()

ΒιΆΉΤΌΕΔ Wiltshire—World War One At ΒιΆΉΤΌΕΔ

Places in Wiltshire that tell a story of World War One

![]()

Medicine—World War One At ΒιΆΉΤΌΕΔ

Hospitals, medical pioneers and the nursing contribution

More clips from World War One At ΒιΆΉΤΌΕΔ

-

![]()

The loss of HMY Iolaire

Duration: 18:52

-

![]()

Scotland, Slamannan and the Argylls

Duration: 07:55

-

![]()

Scotland Museum of Edinburgh mourning dress

Duration: 06:17

-

![]()

Scotland Montrose 'GI Brides'

Duration: 06:41