Kenilworth, Warwickshire: Kenilworthβs Got Mail

Graphic descriptions of trench life by a postman serving on the front line

In 1914, Kenilworth was just a small town with a population of just over 5,500 people. But it had all the necessities: a butcher, a baker and a post office. The post office became crucial in keeping the 836 men at the front in touch with their families at home.

Kenilworth Advertiser, 12 September 1914: βThe extraordinary flocking of young men to the colours, wonderful enthusiasm pervaded the town during last week, probably two out of every three single men of suitable age and physical standard joined the forces.β

The post office building is still here, although it is only a sorting office on the High Street. Just inside, there is a handwritten scroll commemorating the 12 members of staff who served in the war, one of those men was Private James Harris.

Susan Tall is a local author who has extensively researched the men who fought from Kenilworth: βJames Harris was a Kenilworth postman and a reservist with the British Expeditionary Force. At the outbreak of war he was sent to France, arriving on an adapted cattle boat. James wrote many letters home to his wife which were published and shared with those in the town.β

Without phones, email and text messages, letters were vital for keeping in touch with loved ones. Letters were often short and to the point, they were used much like text messages today. The postal system was incredibly efficient, in some places was taken up to 12 times a day. The post office became a thoroughfare for many letters to and from Kenilworth soldiers at the front.

Some excerpts from soldiersβ letters:

βWe are having rotten weather here, walking about in mud up to our kneesβ¦β

βI should call it hell upon earth. The rifle bullets whistled over the trenches. At night the bursting of the shells could be seen in every direction. . . we had to bob down whenever they came. We were like rabbits bobbing up and down.β

The war started in August 1914 and it wasnβt long before the first fatalities from Kenilworth were reported in October.

Only seven weeks after his marriage, Private Henry Barnett was the first Kenilworth Reservist killed in action. He left on 8 October 1914. His wife only received one letter in which he told her not to worry, that heβd be alright and asked her to send some cigarettes. Private Harris has no known grave. His name is recorded on the famous Menin Gate in Ypres, Belgium.

And the letters were not only written on paper; one was written on a paper serviette following an exchange of Christmas cake with the Germans during the infamous Christmas Day truce of 1914, reading:

βI daresay you will be surprised at me writing a letter on such paper as this, but you will be more surprised when I tell you that it contained cake given to one of our men by a German officer on Christmas Day, and I was given some of it. We had not been in the trenches very long on Christmas Eve before we were shouting and wishing one another a merry Christmas. Then we invited them to come over, so they shouted βNo Shootβ and we said the same. We met half way. We were able to bury our dead, some of whom had been lying there for six weeks or more.β

But the war continued and got worse: more muddy, more treacherous and the letters became more graphic:

βThe longest day of my life was a week last Sunday. We marched all day and night and it rained like hell. We got going, and overcame their lightsβ¦my word it grew hot; we were only 80 yards from their trenchesβ¦I got my dose of gas β the devils dropped their stinkers right on top of us.β

Meanwhile the post office was itself changing with more and more men joining the forces their places had to be taken by women and girls especially when in 1916, conscription was introduced. Initially only single men deemed fit enough to fight were called up but soon married men followed.

Susan continues: βKenilworthβs local butcher, who, despite being able to seek exemption, had closed down his business to do his bit. He died, the town felt great sadness. And three Kenilworth girls, Alice Reeve, Beatrice Peck and Edith Aitken became telegraph messengers, to fill in the gaps that the men who went to war left.β

The letters from postman James Harris continued throughout the war. For many soldiers letters helped maintain their connection and thoughts of home in difficult circumstances.

Of the 836 people from Kenilworth who went to war; 697 survived and 139 died.

Location: Kenilworth Post Office, Kenilworth CV8 1AA

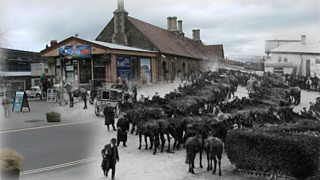

Image shows three Kenilworth girls who became telegraph messengers during the war.

Presented by Marian McNamee and letters narrated by Mark Frampton and Andrew Wooley

Duration:

This clip is from

Featured in...

![]()

Children—World War One At ΒιΆΉΤΌΕΔ

Experiences of children across the UK

![]()

ΒιΆΉΤΌΕΔ Coventry & Warwickshire—World War One At ΒιΆΉΤΌΕΔ

Places in Coventry & Warwickshire that tell a story of World War One

![]()

War at ΒιΆΉΤΌΕΔ

Refugees, internment, training and protest.

More clips from World War One At ΒιΆΉΤΌΕΔ

-

![]()

The loss of HMY Iolaire

Duration: 18:52

-

![]()

Scotland, Slamannan and the Argylls

Duration: 07:55

-

![]()

Scotland Museum of Edinburgh mourning dress

Duration: 06:17

-

![]()

Scotland Montrose 'GI Brides'

Duration: 06:41