Harry Thorntonβs death provokes riots.

John Humphrys reports on the escalating violence following the death of Harry Thornton who was shot by a soldier when his engine backfired outside a police station in west Belfast.

John Humphrys reports on the escalating violence following the death of Harry Thornton who was shot by a soldier when his engine backfired outside a police station in west Belfast.

The report begins with footage of an army vehicle removing the burning remains of a car used to barricade Leeson Street and leaving it near Clonard Cinema on the Falls Road. John Humphreys then delivers his report to camera from the area. He says the armyβs war against the gunman has not yet been won. The previous night, Saturday 7 August, βwas the worst night for guns in Belfast since the outbreaks of 1969.β At least 120 shots were fired at soldiers who returned fire but didnβt hit anyone. The riots started on Saturday evening in response to the death of Harry Thornton, 28, a married labourer from Crossmaglen in Co Armagh who was shot dead while he drove his grey Morris A55 van past Springfield Road RUC (Royal Ulster Constabulary) station at 7.35 in the morning. The paratrooper who fired the fatal shot mistook his engine backfiring for gunfire.

Humphrys then shows to camera the new weapon rioters are throwing at the army. It is believed to be samples from concrete castings. We then see night shots of men, women and children praying at a candle lit shrine erected on the spot were Thornton was killed.

The report then moves to the Ardoyne district of North Belfast where there were riots between Catholics and Protestants. The army used CS gas and rubber bullets to disperse the rioters. The latest form of harassment against the army is the so-called petticoat patrol; groups of women who stand on street corners and whistle at soldiers as they pass by. The tactic is used to warn others as soldiers move from street to street in the area. During last nightβs riot, a gelignite bomb thrown from a passing car missed its army target and exploded in a Co-operative grocery store on the edge of the riot area.

Context

In the early hours of Monday morning, 9 August 1971, the Army and police set off in a widespread series of arrest operations in towns around Northern Ireland. During the first morning of βOperation Demetriusβ, 342 people were arrested; just over a hundred of them were released two days later. The detainees were imprisoned in Crumlin Road Prison and on the Maidstone, a soldiersβ billet turned into a prison ship, at Belfast docks.

The Prime Minister, Brian Faulkner, had been facing mounting criticism of his security policies from within his own party, and felt that his only option was to introduce internment without trial to counteract IRA attacks. It was a tactic that he had used successfully against the IRA during the late 1950s; but in 1971, it proved a serious security and political blunder. This time the security forces were operating on out-dated RUC intelligence. In addition, internment intensified the violence. In the three days following the introduction of internment 25 people were killed, the majority shot by the Army. The Parachute Regiment was responsible for 11 deaths in the Springfield area in Belfast alone, including Father Hugh Mullan, shot while administering the last rites to an injured man and Joan Connolly a mother of eight; about 240 houses in Ardoyne were destroyed by fire; a member of the UDR was shot dead in Co Tyrone; and Londonderry experienced protracted rioting as more than 30 barricades were put up in the Creggan and the Bogside.

Most of the new leadership of the IRA escaped the army raids, and β with the exception of two Protestant civil rights activists, Ronnie Bunting and John McGuffin β the measure was used exclusively against the Catholic community. The fact that no loyalists were arrested increased the Catholic communityβs sense of grievance. Subsequent allegations of torture against the people arrested led to an upsurge in recruitment to the IRA and an increase in sympathy and finance for the IRA at home and abroad, particularly from some among the substantial Irish-American community in the United States.

Up to 9 August, 34 people had died in the violence that year. Only three days after the introduction of internment, 25 more people had been killed. Among the dead was Winston Donnell, the first member of the Ulster Defence Regiment to be killed. Thousands of people had been forced to leave their homes in Belfast because of sectarian attacks and many Belfast Catholics left the city for refugee camps across the border.

In the first six months of internment, nearly 2,400 people were arrested; of these 1,600 were released after interrogation. The Army admitted years later that internment was a major mistake.

Duration:

This clip is from

More clips from ΒιΆΉΤΌΕΔ Weekend News

-

![]()

Omagh bomb victims in hospital—16/08/1998

Duration: 02:48

-

![]()

Political reaction to Omagh bomb—16/08/1998

Duration: 02:17

-

![]()

Omagh bomb—15/08/1998

Duration: 03:04

-

![]()

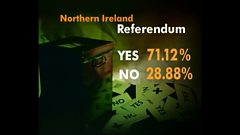

Northern Ireland votes yes to Good Friday Agreement—23/05/1998

Duration: 04:31