AI Macular Degeneration Detection; New Money For Blind Sport

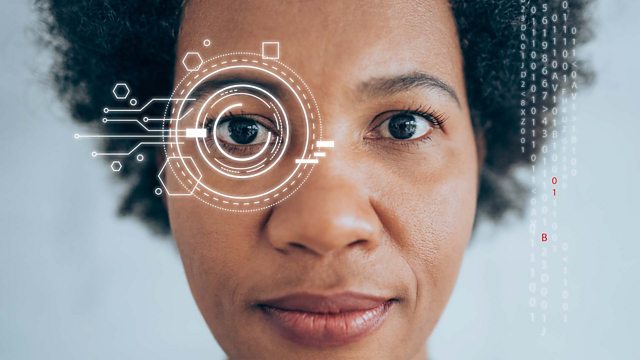

Moorfields Eye Hospital have created an algorithm, for use with artificial intelligence, that is claimed to detect signs of Dry Age Related Macular Degeneration in under 30 seconds

It can be a common occurrence to hear your doctor say 'if only we'd caught this sooner'. Well, the reading department at Moorfields Eye Hospital have created a way to detect signs of one of the most common causes of blindness, all in under 30 seconds. They've done this using artificial intelligence technology and it can detect Dry Age Related Macular Degeneration, or AMD. There is currently no treatment for this condition, unlike the 'wet' form of the disorder, but it is an exciting development in AI medicine. We speak with Dr Konstantinos Balaskas about how it all works and with Cathy Yelf from the Macular Society about potential future treatment for the condition.

Sport England have dedicated £1 million to get visually impaired people more active. It will be delivered through a three year campaign called See Sport Differently. It comes as new figures show that blind and partially sighted people are twice as likely to be completely inactive as people without a vision impairment, with more than half of people with a vision impairment doing less than 30 minutes of physical activity a week.

Paralympics GB medal winners Chris Skelly and Libby Clegg have launched the campaign, we will be speaking with Libby about it, her sporting career and what she plans to do now she's announced her retirement.

Last on

More episodes

In Touch transcript: 28/09/21

Downloaded from www.bbc.co.uk/radio4

Ìý

THE ATTACHED TRANSCRIPT WAS TYPED FROM A RECORDING AND NOT COPIED FROM AN ORIGINAL SCRIPT.Ìý BECAUSE OF THE RISK OF MISHEARING AND THE DIFFICULTY IN SOME CASES OF IDENTIFYING INDIVIDUAL SPEAKERS, THE Â鶹ԼÅÄ CANNOT VOUCH FOR ITS COMPLETE ACCURACY.

Ìý

Ìý

IN TOUCH – AI Macular Degeneration Detection; New Money for Blind Sport

TX:Ìý 28.09.2021Ìý 2040-2100

PRESENTER:Ìý ÌýÌýÌýÌýÌýÌýÌýÌý PETER WHITE

Ìý

PRODUCER:Ìý ÌýÌýÌýÌýÌýÌýÌýÌýÌý BETH HEMMINGS

Ìý

Ìý

Ìý

White

Good evening.Ìý Tonight, diagnosis in the blink of an eye – how artificial intelligence could massively speed up the spotting of potential causes of blindness.Ìý And new money for blind sport – what could a £1 million do for getting more of us out of our armchairs and taking exercise?

Ìý

Clip

It’s about inspiring that next generation and I’d love to continue to support athletes on all levels – grass roots right the way up to elite level – in their sporting journey.

Ìý

White

Double Paralympic sprint champion Libby Clegg, we’ll be hearing more from Libby a little later.

Ìý

But first, how often have we heard a doctor say – if only we could have caught this earlier, there’s more we could have done?Ìý Well, now, it’s being suggested that with the use of artificial intelligence some forms of potential eye disease could be spotted in a matter of seconds.Ìý Conditions which, in the past, would have taken much longer to identify by an individual doctor.Ìý The algorithm making this possible has been developed at Moorfields Eye Hospital and is starting to be used to see early signs of a form of macular disease.

Ìý

Dr Konstantinos Balaskas heads the reading centre at Moorfields where this has all been developed.Ìý Dr Balaskas, first of all, tell us about the condition you’re now able to detect more quickly – it’s called Geographic Atrophy, what is it?

Ìý

Balaskas

Geographic Atrophy is one of the forms of Age-Related Macular Degeneration or for short, AMD, which is the most common cause of sight loss in the United Kingdom, that accounts for more than 50% of certifications of visual impairment.Ìý And AMD has a number of forms and a number of stages of severity.Ìý Geographic Atrophy is one of the advanced stages of AMD.Ìý Your audience may be familiar, also, with a distinction between Wet and Dry AMD and Geographic Atrophy falls under the umbrella of Dry AMD, it’s one of the advanced forms that can cause sight loss.

Ìý

White

And that, of course, is the form of AMD which has, so far, proved very resistant to treatment.Ìý So, what does this change in a way?Ìý Okay, you can diagnose quickly but what does that mean you can do about it?

Ìý

Balaskas

That’s a great question.Ìý Perhaps it would be useful to take a step back and talk about how we detect and diagnose this condition and how we monitor it.Ìý

Ìý

So, we use eye scans, they’re called Optical Coherence Tomography scans.Ìý These are very commonly used and they give very detailed pictures of the back of the eye and they help us not just detect AMD but also distinguish the different forms, that I mentioned before, and that is important because not all forms require the same management.Ìý Wet AMD, for example, that is urgent, needs to be detected early and for which we have effective treatments.Ìý Our ability to prevent sight loss are much greater.Ìý With Geographic Atrophy, which is advanced Dry AMD, the situation is slightly different.Ìý This is a form of AMD that progresses slowly over time.Ìý And early detection is important but even more important is to be able to monitor how this condition grows, progresses, slowly over time.Ìý And these changes can be subtle and require careful inspection by clinicians.Ìý And this is where our AI system can prove extremely useful, by helping clinicians detect these slow changes over time and identify patients that are more likely to progress faster.

Ìý

White

So, does that mean that really people should have very regular eye tests because if you’re going to detect it early people won’t know that they’ve got it just by observation will they?

Ìý

Balaskas

In this particular case of Geographic Atrophy, as you correctly mentioned before, we don’t, as yet, have effective treatments as opposed to Wet AMD.Ìý However, there is good reason for optimism.Ìý There are a number of treatments in advanced stages of clinical trials that show great promise.

Ìý

White

Are these mainly drug treatments?

Ìý

Balaskas

Yes, these are in the form of eye injections.Ìý And the way these treatments will act is by slowing down the progression of these areas of wear and tear that we call Geographic Atrophy.Ìý So, in Dry AMD what happens is parts of the tissue at the back of the eye that contains the cells that are sensitive to light and help us see, they degenerate over time and that slowly progresses.Ìý With this AI system the very exciting thing about it is it can help us detect, not only detect, but also monitor how these areas change over time and once these treatments become available it can help us assess how well our patients respond to our treatment.

Ìý

White

Just a couple of quick questions about the AI method.Ìý I mean just how quickly can they actually reach a conclusion about your eye?

Ìý

Balaskas

That is probably the most exciting element of all.Ìý On average it took our experts in the reading centre who were grading the images, 46 minutes to carefully analyse every scan.Ìý It now takes the AI system 2.04 seconds to do the same task.Ìý And so, that can have a transformative effect on clinical practice.

Ìý

White

Just stay there a moment, I’d like to bring in Cathy Yelf, who’s CEO of the Macular Society, which offers support to people with a whole range of macular disease.Ìý Cathy, you talk to people at the sharp end of these problems every day, what’s your reaction to this development?Ìý Clearly the scientists are excited, is it premature for individuals to be excited?

Ìý

Yelf

No, I don’t think so, I think this is a tremendous achievement and I do congratulate Konstantinos and all the people at Moorfields who’ve done this, it is an amazing piece of work.Ìý It might be that right now patients with Dry AMD, right this minute, won’t know or get direct benefit from it but, as we’ve heard, there are some treatments now for Dry AMD, Geographic Atrophy, in late-stage clinical trials and they will be moving forward to get regulatory approval soon, we hope, and they may be coming into clinical practice in the next few years.Ìý Now, if that happens that will be wonderful but we know, for example, the clinics are full, the clinics are full of people with Wet AMD at the moment and we don’t have enough capacity in clinics to treat the people who need treating fully now.Ìý So, if we double the number of patients that we could treat with intravitreal injections into the eye, then the NHS will buckle, it will absolutely buckle.Ìý And we’ve also got the massive covid backlog as well.Ìý

Ìý

So, there’s a huge amount of innovation going on in the NHS to improve the speed at which patients can be seen in clinic and to improve the speed of treatment.Ìý So, the fact that this is becoming available now and I’m sure the testing with continue, if it’s ready for when these new patients come into the system, that will make an enormous difference to the NHS’ ability to treat it.

Ìý

White

So, how do you balance the excitement that surrounds this kind of development with the inevitable caveat that it always takes time for this to translate into successful treatment?Ìý And, as you said, it takes money, it takes beds, it takes staff.

Ìý

Yelf

It does but this isn’t the only reason why this is useful.Ìý The other really important thing for this kind of technology and this kind of understanding of disease is for research.Ìý So, we know that we have a marvellous treatment for Wet AMD that has made a difference to a huge number of people’s lives and similar treatments, we hope, will be coming through but they’re not the complete solution.Ìý And in all these conditions we’re treating disease really when sight is already affected and it’s quite difficult to turn the clock back then.Ìý What we really want to do is to understand disease and be able to design clinical trials for early stages of AMD before people start to lose their vision.Ìý And it is artificial intelligence, deep learning, machine learning, whatever you want to call it, that is helping us to understand the disease processes and how this disease progresses from the very earliest stages through to the very late point of sight loss.Ìý Because Geographic Atrophy, Dry AMD, is a very long-term condition, it starts very slowly, we know that perhaps a quarter of people over 60 have some form of early or intermediate AMD, but we don’t know who is going to go on and lose their vision and we don’t know why and designing clinical trials, at the moment, the only way we can measure the success of a clinical trial is whether somebody’s sight get worse or not.Ìý And that’s not a really ideal solution if we want to treat disease early, we’ve got to understand the early points of the disease where we can say yes this is definitely progressing now.Ìý And that way you can test interventions earlier in the disease process and possibly get to a point where nobody ever has to lose their vision.

Ìý

White

That is perhaps a long way away but an exciting idea.Ìý

Ìý

Dr Balaskas, is there any danger that this development could sort of erode the personal relationship between ophthalmologist and patient?Ìý After all examination of the eye is also when some of the talking gets done between patient and doctor, patients can ask important questions, is this new AI detection now the standard or will it be the standard?

Ìý

Balaskas

Concerns of that type have been expressed and it is important to take them quite seriously.Ìý In this particular case, it would probably lead to quite the opposite result – it would allow more time for interaction between clinicians and patients.Ìý In essence, it would lead to less time for a doctor spending looking at the screen and trying to interpret these complex scans.Ìý And so, it would liberate clinicians to interact more meaningfully with patients.Ìý AI has the potential to offer the gift of time to clinicians and patients.

Ìý

White

Dr Konstantinos Balaskas, Cathy Yelf, thank you both very much indeed.

Ìý

Now, as the Paralympics amply demonstrated, lack of vision doesn’t have to mean lack of participation in sport.Ìý Still, we can’t all be sporting champions and recent research, by the RNIB, showed that over half of visually impaired people interviewed did less than half an hour of physical exercise a week, way less than the NHS recommendations of 150 minutes.Ìý Now, though, Sport England has come up with a £1 million specifically to help stimulate sporting activity amongst visually impaired people in a three-year campaign run by the RNIB and British Blind Sport.Ìý

Ìý

David Clarke is the RNIB’s Director of Services and a former Paralympics GB footballer himself.

Ìý

David, how are you going to translate this money into actual sporting action?

Ìý

Clarke

Well, thank you Peter, I mean look the statistics you gave are maybe a little shocking but, of course, there’s lots and lots of reasons why that is the case.Ìý And we believe that there are a number of barriers that exist.Ìý Around 48% of those people surveyed said they think that that barrier is their sight loss but 53% of people said there were other barriers that exist as well.Ìý And, most importantly, eight of 10 people we surveyed, said they really would like to do more sport and physical activity.

Ìý

So, the way we’re going to do this is amplify the existing opportunities that exist and organisations and our partners, British Blind Sport and lots of local associations, do a wonderful job of doing this already, we want to amplify that and also increase those opportunities.Ìý We want it to be an expectation of people in sporting venues and sporting facilities that blind and partially sighted people will want to come and do sport.Ìý And, of course, the final tranche is to educate people across the sporting workforce and to ensure that venues and even things like sports equipment and even down to sports broadcasting is accessible.

Ìý

White

But that’s an interesting point, isn’t there a danger that this money which, with the best will in the world, only amounts to 50 pence per visually impaired person, might just be spent on raising awareness, which is a rather vague concept, as opposed to real action?

Ìý

Clarke

This is not just about raising the opportunities with people, as I mentioned, or indeed the expectations, this is about demonstrating to people that it’s absolutely part of their everyday activity to provide opportunities for blind and partially sighted people to play sport and do physical activity like anyone else.Ìý And one of the things I was struck by was that about a third of the people we surveyed said there were sports they’d love to do but they haven’t done, such as things like horse-riding, for example.Ìý So, no, it’s not just about raising expectations, that’s not good enough, it’s actually about changing hearts and minds and getting more and more blind and partially sighted people active.

Ìý

White

Well, someone who’s lending her support to this See Sport Differently campaign is sprinter Libby Clegg, one of our most successful athletes for more than the past decade, peaking with two golds in Rio in 2016.Ìý Libby, welcome back to In Touch, first, tell me, how would you like to see this money spent?

Ìý

Clegg

I would love it to be spent educating people in leisure centres and clubs and making them more aware.Ìý That extra bit of training, for me, is one of the biggest barriers that people face, is that customer service, so that reception desk where they don’t necessarily know how to deal with a visually impaired or blind person.Ìý And, for me, that would be really beneficial to upscale the workforces because sometimes it’s not about adapting the equipment, it’s also about that human touch, that connection with another person that can make all the difference in an environment.

Ìý

White

Because the first contact, if that’s not successful, that can frighten away people for good, can’t it?

Ìý

Clegg

Massively.Ìý I mean I’ve experienced it myself, where not even just in a sporting situation but even going to a café, if I have a really negative experience I won’t go back again and that would be no different than me going to a gym.Ìý Having a negative experience, I’m going to feel uncomfortable, it’s going to heighten my anxiety.Ìý And it’s not just about the visual being in an unknown environment, it’s all the different sounds, different people and it can be really disorientating and it can be quite a scary environment for a blind person anyway.Ìý So, add in that then negative experience just as an additional reason not to go back.Ìý So, if that initial interaction’s really positive you’re more likely to get involved and continue to go.

Ìý

White

How did you get started, how did you develop an interest in sport yourself?

Ìý

Clegg

So, I was always quite competitive, I loved sports day in school and I’d taken dance classes when I was really little.Ìý And I just went along to my local athletics club when I was nine and I’d just got diagnosed at the same time and I was very, very lucky that I had a really supportive club.Ìý I also linked up with British Blind Sport, actually, who are a working partnership with the RNIB, and they really supported me in just – not only just the athletics element of it but I also got to meet lots of other children that had visual impairments and it kind of normalised my disability for me and also showed me how I could participate in sport.

Ìý

White

Just on a more personal note, you announced your retirement at the end of these recent Paralympics, what are you going to do now and how are you going to stay fit?

Ìý

Clegg

I’m potentially looking at going into cycling but I’ve never cycled before, so I mean I’ve been on a bike but I’ve not ever been in a velodrome or anything.Ìý So, I’m going to give that a little go.Ìý But, you know, for me, it’s about inspiring that next generation and I’d love to continue to support athletes on all levels – grass roots right the way up to elite level – in their sporting journey because I’ve got lots of experience that I’d like to pass on.

Ìý

White

David Clarke, finally, can people apply for some of this money?Ìý I mean are you looking to – up for ideas on projects from people?

Ìý

Clarke

So, what the initial research did was to give us a basepoint to work from and now we’re in the process of formulating what that programme will be.Ìý We know, for example, that one of the big things we’re going to be doing towards the back end of next year is a mass participation event.Ìý But we are absolutely open to ideas and they can be shared with us.Ìý I would encourage people to go to the See Sport Differently section of the RNIB website, there’s lots of brilliant tools there which British Blind Sport have shared with us around activities.Ìý This is about getting more and more people active and making it easier.Ìý And I was really struck by something that Libby said there – I was lucky enough to have a supportive club.Ìý It shouldn’t be about luck and we intend to make it that way.

Ìý

White

David Clarke, Libby Clegg, thank you very much indeed.Ìý

Ìý

And if you’ve got ideas you might like to tell us about them.Ìý Also, tell us how you keep fit or what’s stopping you.Ìý And with all the talk about social care, over the last few years, just another topic we’d like to hear from you about, we want to hear from people who are newly losing their sight and need help with relearning daily living skills – are you getting the help you need and how long is it taking?Ìý You can email us at intouch@bbc.co.uk.Ìý You can leave a voice message on 0161 8361338 or visit bbc.co.uk/intouch where you can get more information and download tonight’s and previous editions of the programme.

Ìý

From me, Peter White, producer Beth Hemmings, studio managers Mike Smith and Sue Stonestreet, goodbye.

Ìý

Ìý

Ìý

Broadcast

- Tue 28 Sep 2021 20:40Â鶹ԼÅÄ Radio 4

Download this programme

Listen anytime or anywhere. Subscribe to this programme or download individual episodes.

Podcast

-

![]()

In Touch

News, views and information for people who are blind or partially sighted