Domesday Reloaded

Historian Michael Wood surveys the rise, fall, and rehabilitation of the most ambitious digital survey ever carried out.

Historian Michael Wood surveys the rise, fall, and rehabilitation of the most ambitious digital survey, ever carried out. The project took the name of William the Conqueror's Domesday book and was completed in time for the 900th anniversary of its namesake,

The anniversary prompted Βι¶ΉΤΌΕΔ TV producer Peter Armstrong to propose an equally ambitious project. Using money left over from the successful country wide roll-out of the Βι¶ΉΤΌΕΔ Micro computer to schools, he hit upon the idea of compiling something similar to the Domesday Book. He wanted to collect pictures and text, gathered by children everywhere, in a digital format, and ultimately deliver a computer resource for every library and school.

The country was divided into 3x4 km blocks, and for two years community groups from schools, Scout & Guide troops, Women's Institutes and Tourist Information Centres, were corralled into diligently gathering information about local life in the 1980s. After a huge press launch over a million people took part in the survey, and their stories were astonishingly diverse. 14,000 schools took up the challenge and approached the project in many different ways. From the small Scottish school who undertook a full census of the wildlife on their island, to the (newly) ex-miners' children who wrote poetry about their hopes for a non-coal powered future.

The stories and photographs were eventually loaded onto the Domesday machine and the technology was demonstrated to at the highest level, from the Queen, to the then Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher and to President Mitterand.

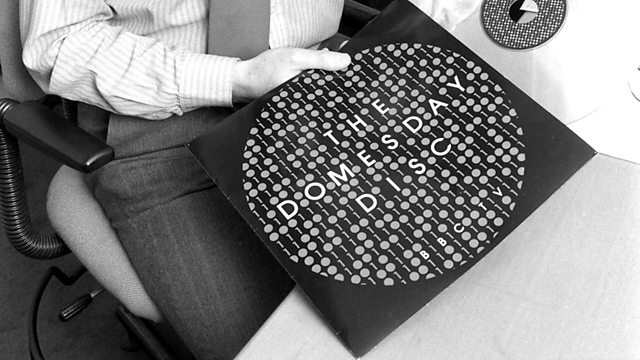

However, when the final machine - a slightly Heath-Robinson combination of a Βι¶ΉΤΌΕΔ Master, a tracker-ball pointer (this was pre-mouse) and a large 12 inch video disc player (this was pre-CD Rom) - was unveiled in November 1986, it was frustratingly expensive. At almost Β£5,000, the machines were outside the price range of nearly all libraries and schools. So most of the people involved in gathering the data and snapping the photos never even saw the fruits of their labour.

As time went by, the Βι¶ΉΤΌΕΔ scrapped its interest in interactivity, and the project decayed. All the data so painstakingly collected was locked up in obsolete technology - a good example of the Digital Dark ages of the 1980s.

By 2002 the hidden Domesday data started to gain cult status and was a treasure trove for digital archaeologists, many of whom have laboriously excavated the data from the disintegrating discs. Now, 25 years after the original project, that digital archaeology is resurrecting a history of Britain never seen before and data from the 1986 Domesday project is now being made available via the internet at www.bbc.co.uk/domesday.

Last on

More episodes

Broadcasts

- Sat 14 May 2011 20:00Βι¶ΉΤΌΕΔ Radio 4

- Mon 16 May 2011 15:00Βι¶ΉΤΌΕΔ Radio 4