Mexican Codex Map

Neil MacGregor explores the overlapping of faiths across the globe around 400 years ago. Today, he is with a map that shows what happened after Catholic Spain's conquest of Mexico.

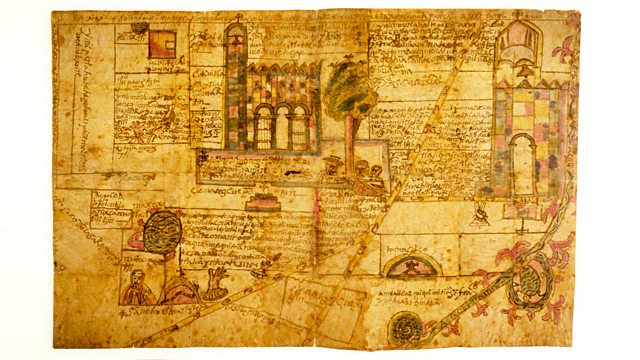

The history of humanity as told through one hundred objects from the British Museum in London. This week Neil MacGregor is looking at the co-existence of faiths - peaceful or otherwise - across the globe around 400 years ago. Today he is with a document that shows what happened after Catholic Spain's conquest of Mexico - it's an old map, or codex, that was made at the height of the Spanish church building boom in Mexico. Neil uses the object to consider the nature of the Spanish conquest and to explore what happened when Catholic beliefs were assimilated alongside older pagan beliefs. The historian Samuel Edgerton offers an interpretation of the map that shows churches alongside older temples, and the Mexican born historian Fernando Cervantes considers the ongoing legacy of the great Christian conversion.

Producer: Anthony Denselow

Last on

![]()

More programmes from A History of the World in 100 Objects related to leaders & government

About this object

Location: Mexico

Culture: Aztec, Maya and Central America

Period: Late 16th century

Material: Paper

Μύ

This Mexican map was made 50 years after the Spanish conquered the Aztecs in AD 1521. It is a property plan illustrating the foundation of two towns in the region of Tlaxcala, Mexico. Each town is represented by its newly built church - Santa Barbara Tamasolco (left) and Santa Ana (right). The script is written in an adapted form of the local language with an imported European alphabet. A list of the names of the main landowners on the map reveals that several Spanish settlers have intermarried with native aristocrats.

How did the Spanish convert native Mexicans to Christianity?

The Spanish justified their conquest of Mexico by arguing that it was their duty to convert the native population to Christianity. The people of Tlaxcala were not conquered but fought with the Spanish against the Aztecs. They were also supposedly the frst Mexican Indians to be baptised and become Christians. To attract converts missionaries often combined existing Mexican and Christian rituals. Aztec ancestor worship was merged with All Saints Day to create the Day of the Dead, still celebrated in Mexico today.

Did you know?

- Tlaxcala means 'the place where tortillas are made'. In Mexico, Tortillas have a symbolic association with human flesh.

Mexican identity and Religion

By Fernando Cervantes, historian

Μύ

I think, as any visitor to Mexico would realise, you can’t really get away from Catholicism, it’s everywhere, it’s pretty overwhelming. The problem with the question [of] Mexican identity, is that you can’t really get away from notions of nations, nationalism and nation building. Here you come across a very vigorous, a very strong nationalistic ideology which has very often been very worried about the church, very anti-religion in some senses because they see the church and Catholicism as part and parcel of the colonialist mind, in other words part of the imposition of the various structures that nationalism is trying to reject, the colonialism, the aggressive colonialism of the West.

It’s a very ambivalent type of thing because you will have heard that even the most atheistic Mexicans will never deny they’re devoted to the Virgin of Guadalupe, for instance. It very often comes up, that despite their unbelief, despite their qualms about the whole of the Christian tradition in Mexico and the negative effects that they claim it has had, they still are very keen to be Guadalupents, to be part of the folkloric Catholicism as it were. This is where the kind of Catholic substratum comes through very strongly, that you can’t really square the circle of being Mexican and not being in some senses Catholic.

I think this is where you can see how strong the early evangelisation was and how alive it still is nowadays.

New churches

By Samuel Edgerton, professor of art history

Μύ

Santa Barbara Tamasolco has in front of it a large courtyard. Now this courtyard is interesting because it’s what is today called an atrio or patio and this was a kind of innovation that the friars introduced to the buildings of these churches in Mexico because in the beginning the churches were often small and you could not crowd all the Indians who were being brought in here to be converted. And so you had them stand in this large courtyard or patio (as the original language or at least the earlier documents refer to them) and there they were preached to from an open chapel.

A friar would stand in an open chapel, some kind of an arched framework around him, and then preach to the Indians and then convert them, sprinkle them with holy water and over time as the churches got bigger the congregation could go inside the churches. But in the beginning this interesting atrio or patio is a peculiar characteristic of Mexican churches and you may see many of them in churches of this day.

These churches – many of them could be compared to some of the great medieval churches in Europe. Certainly in size and grandeur and I think that’s one of the great splendours of colonial Mexico which has somewhat been overlooked in modern times.

Transcript

Broadcasts

- Thu 30 Sep 2010 09:45Βι¶ΉΤΌΕΔ Radio 4 FM

- Thu 30 Sep 2010 19:45Βι¶ΉΤΌΕΔ Radio 4

- Fri 1 Oct 2010 00:30Βι¶ΉΤΌΕΔ Radio 4

- Thu 9 Sep 2021 13:45Βι¶ΉΤΌΕΔ Radio 4

Featured in...

![]()

Mapping the World

A collection of programmes relating to maps.

![]()

Leaders and Government—A History of the World in 100 Objects

More programmes from A History of the World in 100 Objects related to leaders & government

Podcast

-

![]()

A History of the World in 100 Objects

Director of the British Museum, Neil MacGregor, retells humanity's history through objects