Indus Seal

Neil MacGregor arrives at the great Indus Valley civilisation and examines 4,500-year-old stone stamps from a city building boom of the period.

The ancient city of Harappa lies around 150 miles north of Lahore in Pakistan. It was once one of the great centres of a civilisation that has largely disappeared, one with vast trade connections and boasting several of the world's first cities. At a time when another great civilisation was being forged along the banks of the river Nile in Egypt, Neil MacGregor investigates this much less well-known civilisation on the banks of the Indus Valley.

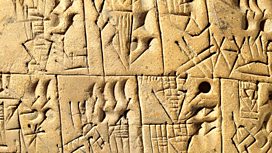

He introduces us to a series of little stone seals that are four-and-a-half thousand years old, covered in carved images of animals and probably used in trade. The civilisation built over 100 cities, some with sophisticated sanitation systems, big scale architecture and even designed around a modern grid layout. The great modern architect Sir Richard Rogers considers the urban planning of the Indus Valley, while the historian Nayanjot Lahiri looks at how this lost civilisation is remembered - by both modern India and Pakistan.

Last on

![]()

Discover more programmes from A History of the World in 100 Objects about communication

About this object

Location: Indus Valley (Pakistan, India)

Culture: Ancient South Asia

Period: About 2550-2000 BC

Material: Stone

Μύ

This seal was found in the 1870s and led to the discovery of an ancient civilisation in the Indus Valley. It was probably used to close documents and mark packages of goods. This suggests that the Indus civilisation was part of an extensive long-distance trading network. The animal on this seal was originally mistaken for a unicorn but is now thought to be a bull. The seals carry the oldest writing in South Asia. It has yet to be deciphered.

What was the Indus Civilisation?

The earliest civilisation in South Asia developed along the Indus river and India's western coast. The Indus civilisation produced writing, built large cities and controlled food production through a central government. Unlike Egypt and Mesopotamia, the Indus civilisation was not dominated by powerful religious elites. No temples were built and no images of state gods or kings have been found. Deforestation, climate change and a series of invasions all contributed to the Indus civilisation's decline in 1500 BC.

Did you know?

- The Indus civilisation had complex sanitation systems and there is even evidence that houses had bathrooms.

Legacy of the Indus Valley civilisation

By Nayanjot Lahiri, Professor of History, University of Delhi

Μύ

In 1924 when the civilisation was discovered, India was colonised. So to begin with there was a great sense of national pride and a sense that we were equal if not better than our colonisers and considering this that the British should actually leave India. This is the exact sentiment that was expressed in the Larkana Gazette – Larkana is the district where Mohenjodaro is located.

After independence, the newly created state of India was left with just one Indus site, in Gujarat and a couple of other sites towards the north, so there was an urgency to discover more Indus sites in India. This has been among the big achievements of Indian archaeology post-independence – that hundreds of Indus sites today are known, not only in Gujarat but also in Rajasthan, in Punjab, in Haryana, and even in Utter Pradesh.

The great cities of Harappa and Mohenjodaro, which were first excavated, are in Pakistan, and subsequently one of the most important pieces of work on the Indus civilisation was done by a Pakistan archaeologist – Rafique Mughal (presently a professor at Boston University) who discovered nearly 200 sites in Pakistan and Cholistan. But my own sense is that on the whole the state of Pakistan has been much more interested, not exclusively but significantly, in its Islamic heritage so I think there is a greater interest in India as compared to Pakistan.

There is not a competition but a certain kind of poignant sentiment that I have when I think of India, Pakistan and the Indus civilisation, for no other reason than that the great remains - the artefacts, the pottery, the beads etc that were found at these sites - are actually divided between the two states. Some of the most important objects were actually divided right down the middle – like the famous girdle from Mohenjodaro. It’s no longer one object, it’s really two parts that have been sundered like pre-independent India into India and Pakistan - these objects have met with a similar fate.

A spiritual legacy

By Nayanjot Lahiri, Professor of History, University of Delhi

Μύ

The Indus civilisation has a legacy which would resonate with any Indian who walks through the Harappan Gallery of the National Museum. There are so many objects there that you feel a complete affinity with.

For example you see a lot of shell bangles that are still worn by women, especially married women, in many parts of India. You see particular kinds of pictures inscribed on seals which show tree worship, and tree worship can be seen anywhere in India, including in urban Delhi. You can see figures in what appear to be in yogic postures, figures in meditation surrounded by animals, things you feel familiar with.

Similarly, in the Harappan gallery there is this extraordinary miniature terracotta phallic emblem which is actually set in what looks like to any Indian a Yoni. Somebody who is not politically correct as historians tend to be – just an ordinary Indian – he would tell you that this is a Shiva linga.

You think of the great bath of Mohenjodaro, you think of the extravagant use of water - there was a well for every 3/5 houses - then you think how finicky Indians are about their personal hygiene and how important water is to us. It doesn’t appear alien just because it belongs to the third millennium BC.

Now I am not trying to say that we can trace modern Hinduism from the Indus civilisation but there are things about the Indus civilisation which become a part of later Hinduism.

Transcript

Broadcasts

- Wed 3 Feb 2010 09:45Βι¶ΉΤΌΕΔ Radio 4 FM

- Wed 3 Feb 2010 19:45Βι¶ΉΤΌΕΔ Radio 4

- Thu 4 Feb 2010 00:30Βι¶ΉΤΌΕΔ Radio 4

- Wed 6 May 2020 13:45Βι¶ΉΤΌΕΔ Radio 4

Featured in...

![]()

Communication—A History of the World in 100 Objects

A History of the World in 100 Objects - objects related to communication.

Podcast

-

![]()

A History of the World in 100 Objects

Director of the British Museum, Neil MacGregor, retells humanity's history through objects