What's so great about Stravinsky?

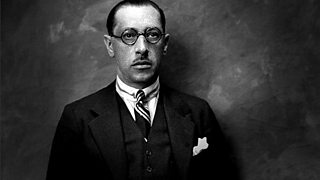

Prof Jonathan Cross captures the multi-faceted genius of the mercurial Igor Stravinsky.

What's so great about Stravinsky? Well, The Rite of Spring. Obviously. If you know only one work by Igor Stravinsky, then it’s likely to be this. A landmark of modernism as world changing as Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, Joyce’s Ulysses, Chanel’s Little Black Dress, or the Ford Model T. More than a hundred years since its premiere it still has the power to shock.

Choreographers keep returning to it to speak of their own time, from the unforgettable feminist reading of Pina Bausch, to Seeta Patel’s reworking in classical Indian dance forms, and Akram Khan’s extraordinary reinvention iTMOi ("in the mind of Igor").

Premiered in 1913 on the eve of the First World War, its elemental rhythms, strident harmonies and haunting folk-like melodies produce a work that is simultaneously ancient (pagan ritual) and modern (of the machine age).

It’s easy to forget it’s a ballet about mob rule and human sacrifice. But maybe that’s precisely why its power is undiminished in our troubled world, where armed thugs storm the Capitol, where a superpower brutally persecutes its Uyghur Muslim minority, and where the innocent of Myanmar and Hong Kong are mown down for peaceful protest. It confronts us with the inhuman side of human nature. The Rite is more than just a dance.

But Stravinsky, too, is more than just The Rite. In part the richness of his music is to be found in its variety, registering a life touched by war, revolution, loss and death, a life lived mainly as an émigré.

His early years were spent in St Petersburg in the shadow of his teacher Rimsky-Korsakov, crowned by his first international success The Firebird. This ground-breaking ballet score revealed Stravinsky’s innate theatrical sense, which subsequently manifested itself in all manner of colourful stage works such as Mavra, Oedipus Rex, Persephone and The Rake’s Progress.

In exile in Switzerland during the war years Stravinsky produced some of his most overtly Russian works, Renard and Les Noces among them, drawing nostalgically on the traditions of a native land now lost to him. In France between the wars he remade himself as a Western European, looking back to the 17th and 18th centuries, rebuilding his musical language out of the ruins of war.

Stravinsky’s music speaks of its time in all its contradictions, and it continues to speak to us now.

Apollo, for instance, espouses classical order and French chic, echoing the new Art Deco style around him in Paris. It also marks the beginning proper of the most fruitful professional relationship with choreographer George Balanchine, with whom he went on to make the landmark ballets Orpheus and Agon.

Settling in the USA after 1939, Stravinsky continued to refine his style, culminating in some beautiful late (and too frequently overlooked) works like Canticum Sacrum and the Requiem Canticles.

In real life, Igor Stravinsky was not a great man. He was a liar and a cheat, he could be mean and spiteful, he treated his first wife shamefully, he spouted anti-Semitic filth, he was obsessed with money.

But maybe because of, rather than in spite of, the fact that he was a flawed individual, his music appears to speak with an authentic voice from behind its many masks.

Yes, it’s often playful, but equally it can be deeply spiritual and profoundly moving – extraordinary from a composer who once claimed that music is "essentially powerless to express anything at all." Stravinsky’s music speaks of its time in all its contradictions, and it continues to speak to us now. It is ultimately in this very complexity, simply and directly expressed, that Stravinsky’s enduring legacy is to be found.

Jonathan Cross joined Oxford University Faculty of Music in 2003, where he is Professor of Musicology, and Student and Tutor in Music at Christ Church. He has written, lectured and broadcast widely on issues in 20th-century and contemporary music, and in theory and analysis. His publications include the highly acclaimed The Stravinsky Legacy (Cambridge University Press, 1998); a comprehensive study of the work of Harrison Birtwistle (Faber and Faber, 2000); and an edited companion to the music of Stravinsky (Cambridge, 2003).

-

![]()

What's so great about Stravinsky

Programmes and features on Radio 3 marking the 50th anniversary of the death of Igor Stravinsky, "the father of 20th-century music".

-

![]()

Composer of the Week: Stravinsky

Donald Macleod provides the latest thinking as he explores the life and work of Igor Stravinsky.

-

![]()

Stravinsky and the Diaghilev era

Donald Macleod explores Igor Stravinsky's life and work up to the end of World War I.

-

![]()

Discovering Stravinsky

Listen to programmes examining the life and works of Igor Stravinsky.

-

![]()

Discovering Music: The Firebird

Stephen Johnson and the Βι¶ΉΤΌΕΔ SSO explore the 1945 version of Stravinsky's Firebird suite.