What do the Taliban believe?

It is 20 years since the fundamental Islamist organisation, the Taliban, were removed from power in Afghanistan by the US-led military coalition.

But with the recent withdrawal of foreign forces begins a new era of Taliban rule, labelled by some as “'Taliban 2.0”.

The eyes of the world are now fixed on how they will govern their “Islamic Emirate”.

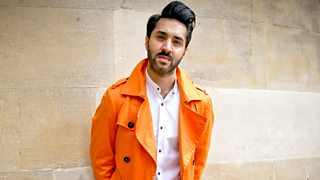

In Radio 4's Beyond Belief, Mobeen Azhar and guests explore what the Taliban believe, how they have justified their actions theologically and whether any of those core beliefs are likely to change.

The Taliban’s roots are in the Deobandi movement

Deobandism began as a seminary in the town of Deoband in India (from which it takes its name) around 150 years ago. John Mohammed Butt, an Islamic scholar, broadcaster and the first Westerner to graduate from the Darul Uloom Deoband in India, explains how it was founded as a reaction to the 1857 uprising against the British that was cruelly crushed by the ruling forces. In the face of this onslaught, Indian Muslims wanted to take steps to protect themselves, their culture and their religion. It was set up on pacifist grounds, explains John: “They thought it would be a fortress of Islamic learning in which Western thought would not encroach.”

However, the influence of the Afghani Taliban is from Pakistani Deobandism, which is much more political, explains the scholar. “In Pakistan, it was an Islamic state, it was created in the name of Islam, so obviously the Deobandi ulama [guardians] who were there thought there should be an Islamic system. And that’s really where the Afghan Taliban derive their inspiration.”

Notably, the new leadership of the Taliban are predominantly made up of graduates of the Deobandi seminaries in Pakistan.

What do Deobandis believe?

The Deobandi school of thought is neither Reformist nor Salafist, explains Dr Sayed Hassan Akhlaq, an Afghan-Iranian philosopher at Coppin State University. “Salafist people are saying let’s return to the earlier Muslim, and Reformist and Modernist Muslims are saying let’s find a way to combine Islam with new developments in science and sociology and politics.

“But Deobandi are a school that’s saying let’s keep the history of Islam alive, particularly the traditional Islam… They just want to revive and give a new life to the tradition of Islam.”

Reliance on pre-modern texts

Fundamentally, the Deobandi understand Islam in the context of a limited number of texts – exclusively and uncritically – that have their roots in a pre-modern context, explains Dr Haroun Rahimi, Assistant Professor of Law at the American University of Afghanistan.

“That’s what makes them traditionalist, backward looking, and that also makes it harder for them to embrace the advances, the changes, the evolution that have happened in society – Muslim society and outside.”

For example, if asked whether or not women can hold leadership positions in society, a Deobandi scholar would consult a limited number of classical texts, most of which date back to Moghul India and, as a result, answer no.

"There is detailed opinion (for a different context) within Deobandi texts that limit the public participation of women."

There is detailed opinion (for a different context) within these texts that limit the public participation of women.

A Modernist, in contrast, would argue that Islam is not limited to text but that Islamic Fiqh (or jurisprudence) is a discourse, an open debate that continues, and that yes, women can take a prominent position in society.

But not all of the Taliban’s beliefs are rooted in scholarship and scripture...

Pashtun culture

A large influence on the Taliban belief system is Pashtun culture, an ancient way of life native to North-western Pakistan and Southern Afghanistan.

It is “extremely conservative”, says John. For example, Pashtuns in Afghanistan, especially rural areas, generally don’t send their girls to school. If they do, they might send them only to Quran class. In traditional Pashtun culture, girls are expected to get married between the ages of around 16 and 18.

Sayed agrees that this cultural influence often overrides religious guidance. In Hanafi jurisprudence (one of the four Sunni schools of religious law), women can act as a judge. “But look at the Taliban,” says Sayed. “They claim they are Hanafi but they are not practicing Hanafi Fiqh, they are just practicing the Pashtun culture.”

Political agenda

As well as the religious and cultural driving forces, there is the factor of politics, says Haroun. The Taliban use Deobandi, but they also do many things that would violate the Deobandi world view to achieve their other political objectives.

“I don’t think there is a sophisticated thinking in terms of systemic implementation of Deobandi world view with regards to Taliban,” he says. For example, during their rule in the 1990s, they were collecting religious tax from the trade in opium. “No self-respecting scholar who was not invested in an insurgency would give sanction to profiting from trade in opium.”

Muddling religious guidance with law

John believes the Taliban get mixed up between law and Fatwa (non-binding legal opinion on a point of Islamic law). “The problem with the Taliban now is they’re making laws,” he states.

They’re mixing religious edicts with laws that can be implemented on the street.

"In things like music, the Taliban get mixed up between law and fatwah [advice]"

There are ways in which music is allowed within Islamic jurisprudence...

For example, although music should not distract you from your worship and your devotion, there are ways in which it is allowed within Islamic jurisprudence. For instance, the Holy Prophet allowed music to be played to publicise a marriage. But the Taliban enforced a blanket ban, based on a legal and literal interpretation of some Islamic texts. “It’s giving a legal context to something which should be a fatwah,” says John. “A fatwah is not legally binding, it’s advice.”

What does the Taliban belief system mean for those living under their rule?

Dr Weeda Mehran is a lecturer at the Department of Politics at the University of Exeter. She grew up in Afghanistan in the 1990s and was fifteen years old when the Taliban took over her city. “I was a school girl, full of dreams about things that I wanted to do in life, and it all changed over night,” she recalls.

Under Taliban rule she couldn’t go to school. As a girl, she wasn’t even allowed out of the house without being accompanied by a male member of the family. Women could not work. There was also a strict dress code. “Women and men had to wear certain dresses and outfits in public.” Music, watching television and taking pictures were all prohibited. “Paintings were not allowed,” says Weeda. “If you had a painting of an animal or a human being, they would tear it apart.”

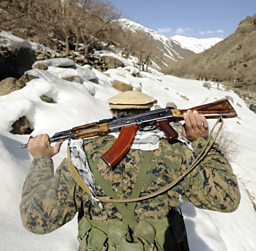

For those who ignored the rules, the consequences could be brutal. The Taliban would humiliate, imprison and beat and those who didn’t toe the line. Public executions were common. Ethnic and religious minorities were targeted and killed.

Will things be different under Taliban 2.0?

There is some evidence that this incarnation of the Taliban will be different. The use of social media is a development. “They did not allow any living things to be depicted. Now all their fighters have smart phones. They engage in sophisticated social media campaigns,” says Haroun.

Although their core beliefs have not changed, their application in a modern, 21st century society certainly has, says John.

But in terms of the policies they want to implement, and how these will affect the people of Afghanistan, only time will tell whether there has been any significant change.

-

![]()

Listen to What do the Taliban believe?

Mobeen Azhar and guests explore what the Taliban believe, how they have justified their actions theologically and whether any of those core beliefs are likely to change.

Further listening on Βι¶ΉΤΌΕΔ Radio

-

![]()

Beyond Belief

Exploring the place and nature of faith in today's world.

-

![]()

The Deobandis: India

Owen Bennett Jones tells the story of India’s Deobandi school of Islam, which has inspired both a peaceful global missionary movement and the Taliban.

-

![]()

The Deobandis: Pakistan

Owen Bennett Jones heads to Pakistan where Deobandi Islam has inspired violent groups like the Taliban as well as a peaceful missionary movement.

-

![]()

Islam and science

Writer and journalist Ehsan Masood explores the status of science in the modern Islamic world.