Eight things you might not know about the Great Fire of London

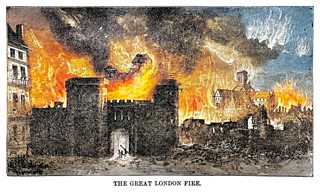

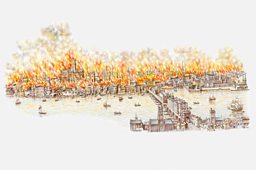

In September 1666, the Great Fire of London consumed hundreds of acres of houses, shops, churches, and government buildings. But what effect did politics and memories of a recent civil war have on the spread of the fire, and the hunt for someone to blame? And once the flames had died down, how did the people of the city rebuild what they’d lost? All is answered in A Short History of the Great Fire of London, on Βι¶ΉΤΌΕΔ Sounds.

Written by Danny Marshall, narrated by John Hopkins and with insights from historian Rebecca Rideal, here are just a few of the facts they dig up from the ashes…

1. Pudding Lane wasn’t named after desserts

The Great Fire famously started at Thomas Farriner’s bakehouse on the tasty-sounding Pudding Lane. But this lane was not named after sweet treats; “pudding” is actually a medieval name for “organ meat” or “offal” – which was carted away from the butchers of Eastcheap to be dumped in the river Thames. Yum.

2. The initial response was slow

On hearing of the fire, King Charles II sent for Sir Thomas Bloodworth, the city’s Lord Mayor, to demolish houses in order to stop the fire’s spread. But not wanting to cede influence or power to the King, Bloodworth ignored this request and went back to bed. Locals initially tried to put out the fire with lines of buckets of water, to no avail.

3. They may have used “fire engines”

A form of fire engine existed in 1666, though nothing like the ones we know today. These were carts with huge barrels of water, with pumps attached. However, these were only used if they could fit down the narrow streets – and usually, they couldn’t.

4. Many blamed the Dutch

Angry and frightened, Londoners began to point fingers as the fire spread. Britain was at war with the Dutch at the time, and it wasn’t long before locals blamed Dutch and French spies for starting the blaze. There were reports of many attacks on foreign-born people during the fire, including the Spanish ambassador’s assistant – which only stopped when a member of the nobility intervened.

The confusion only worsened after the general letter office and the publishing offices of the government's official journal The London Gazette both burned down. With a lack of news and post about the fire, paranoia only grew, and rumours spread beyond London that a full scale attack by the Dutch was imminent.

5. The fire led to a surge in cart hire prices

As people evacuated, an influx of cart owners made their way into the city during the blaze. Some arrived out of a sense of charity, while many others were opportunistic. The cost of hiring a cart rocketed from a couple of shillings to the equivalent of thousands of pounds as desperate Londoners tried to escape through the city gates with their possessions.

6. Refugee camps formed outside the city

With their homes destroyed, many Londoners had nowhere to go. Makeshift tents made of canvas supplied by the navy sprung up in the fields outside the city walls. Food was donated to the starving evacuees from nearby towns and villages. They were also supplied with ship’s biscuit: a dense baked cracker made of salt and flour – the very kind made in the bakery where the fire started.

7. The actual death toll was probably higher

According to official accounts after the Great Fire of London, around six to eight people died during the Great Fire of London. But judging by anomalies in parish records and by comparisons with similar fires, such as the Great Fire of Chicago in 1871, historian Rebecca Rideal believes the actual number to more likely be in the hundreds.

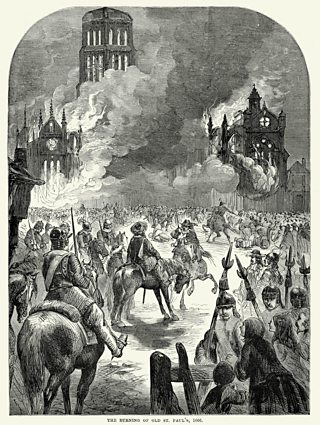

8. A new London rose from the ashes

As well as so much destruction, the fire gave way to new buildings and new ideas. St Paul’s Cathedral was rebuilt by Christopher Wren, along with 51 smaller churches. The Rebuilding of London Act of 1666 also invited new ideas and schemes for the rebuilding of the city. These included a grid system that would be used two centuries later in Paris and cities in North America. However, due to limited building control, most of London’s rebuilding simply followed the city’s old medieval plan.

The streets were rebuilt to be wider, with the new buildings insured. They were designed with better sanitation and, of course, better fire safety in mind.

More from the Βι¶ΉΤΌΕΔ

-

![]()

Real Dictators

Real Dictators explores the hidden lives of history's tyrants. Narrated by Paul McGann.

-

![]()

The Allusionist

An entertainment show about how language works and why we should care.

-

![]()

Stories of our times

The daily news podcast from The Times and Sunday Times. One remarkable story, told in depth. Taking you to the heart of stories that matter.

-

![]()

The Moon Under Water

The podcast where each week Landlord Robbie Knox and his trusty regular, Dan Trelfer, are joined by a special guest to create their perfect pub.