Nine things we learned about… how hypnosis cured Rachmaninov of composer’s block and produced a world masterpiece.

Popularised by the classic film Brief Encounter and by the hit ballad All by Myself, Rachmaninov’s Second Piano Concerto is one of the best loved pieces of music ever written. However, this smash hit for the Russian composer followed his disastrous and critically panned First Symphony three years earlier, in 1897.

The remarkable comeback has been put down to hypnosis sessions he received from viola-playing physician Dr Nikolai Dahl, to whom Rachmaninov dedicated his Second Concerto.

In Radio 3's Hypnotising Rachmaninov, Georgia Mann sets out for Vienna to discover if this early use of an alternative therapy really helped put Rachmaninov’s career back on track. Here are nine things we learned.

1. Rachmaninov was a hot property in 1897

An emotional man and a deep thinker, Sergei Rachmaninov was something of an introvert and was once dubbed by fellow composer Igor Stravinsky as a “six-and-a-half-foot scowl.” Despite all this he was one of the hottest young composers of the Moscow scene, and the premiere of his first symphony in St. Petersburg in 1897, when he was just 23 years of age, was meant to secure Rachmaninov’s place in the Russian musical firmament.

2. His first symphony could have been a victim of musical politics

The premiere of Rachmaninov’s first symphony was a disaster. Among the detractors, César Cui, a composer and critic, suggested that the symphony was fit only to “delight the inhabitants of Hell". Rachmaninov sat huddled on the staircase of the concert hall for most of the performance. He later wrote: “Sometimes I stuck my fingers in my ears to prevent myself from hearing my own music, the discords of which absolutely tortured me. No sooner had the last chords died away than I fled, horrified into the street.”

3. Rachmaninov’s hypnotist was a society darling

After this inauspicious debut, Rachmaninov experienced a “paralysing apathy”. Eventually, after three years of a creative hiatus, his family persuaded him to see Dr Nikolai Dahl, a musician himself and a specialist in hypnosis.

Hypnosis was officially banned in Russia at the time but that doesn’t seem to have put off key movers and shakers in Moscow society, such as opera singer Feodor Chaliapin, composer and pianist Alexander Scriabin and theatre-maker Konstantin Stanislavski. Dahl’s work was even referenced by the playwright Anton Chekhov.

4. Hypnosis was coming of age

Rachmaninov’s – technically underground – treatment had its early roots in the work of physician and astronomer Franz Anton Mesmer who believed in "animal magnetism", an invisible magnetic fluid possessed by all living things that, he believed, if properly manipulated could cure all manner of ills. Mesmer, a musician and friend of the Mozart family, used his theory of animal magnetism as an early form of hypnotising his patients.

Among the acolytes of mesmerism, as it became known (and from which we get the word mesmerise) were notable Victorians, novelist Wilkie Collins and political economist Harriet Martineau who, believing the process to have been beneficial to her illness, once tried to mesmerise a sick cow. There’s no record of the success of this venture.

5. Performative hypnosis was all the rage too

The link between hypnotism and theatrical performance is as deep-rooted as its therapeutic application.

Historian Matthew Sweet references 19th-century farce Freezing A Mother-in-Law “where somebody puts their mother-in-law in hypnosis and puts them in a cupboard under the stairs, trapped there.” Meanwhile, George du Maurier's 1894 novel, Trilby, gave the world the character (and notion) of Svengali who hypnotises the tone-deaf titular character into being a celebrated opera singer.

6. Dr Dahl used positive thinking to treat Rachmaninov

Dr Dahl used very direct, positive thinking and reinforcement to help Rachmaninov, repeating the key phrases of “You will begin to write a concerto. You will work with great facility. The concerto will be of excellent quality.”

Of the method, Rachmaninov wrote: “although it may seem incredible, this cure helped me. At the beginning of the summer I began to compose… New musical ideas began to stir with me – far more than I needed for my concerto.”

7. Rachmaninov’s artistic temperament allowed hypnosis to work for him

Not everyone is susceptible to hypnosis, but Vienna-based hypnotherapist Dr Stella Nkenke believes that Rachmaninov was receptive because of his creative nature.

“Artists are very good objects for hypnosis… they're in a natural trance, they cannot do it without an altered state.” Dr Nkenke believes this natural trance not only helps artists and musicians process information, but it can help them conquer performance anxiety.

“If I tell you ‘there's no need for fear’ that does not help you, but if you experience, in a trance, that you can go on the stage and perform, then that is much stronger than any information anybody can give you.”

"My hand did start lifting up, not really with my permission..."

A sceptical Georgia Mann submits to a session in Dr Stella Nkenke's "hypnotic chair".

8. Therapy was the cure for classical guitarist Craig Ogden

Just like Rachmaninov, even high level performers today can experience unexpected difficulties. Classical guitarist Craig Ogden turned to hypnotherapy to help him overcome an issue with musical performance. He tells Georgia that he succumbed to the treatment “in the blink of an eye… I entered a trance state, but actually what was going on in my head while I was in the trance state, I don't have any conscious memory of.”

Using a combination of spoken therapy and hypnotherapy, Craig went through various strategies that helped him find security in performance again. One of the strategies involved Craig imagining watching someone performing on a big stage exactly how he wanted to perform. “Then you imagine going to stand behind that person,” says Craig. The final step, echoing what Dr Nkenke says above, involves “becoming that person so that it's you”.

9. Rachmaninov's Second Piano Concerto was a triumph of love

Rachmaninov’s Second Piano Concerto was completed in 1901, the first product of the end of a three-year creative block. The following year, Rachmaninov married his cousin Natalya Satina. Their union had been held up by the Russian Orthodox Church, and the delay may have been a further cause of the composer’s slump.

“For me, this concerto is definitely full of hope. It seems like his creativity was reborn with this piece… it's just so full of colour,” says pianist Katya Apekisheva.

Georgia agrees. “In all its tender climactic magnificence, it’s the ultimate expression of a composer who had learned to love again, maybe not just to love his new wife, but also just maybe himself.”

-

![]()

Listen to Hypnotising Rachmaninov

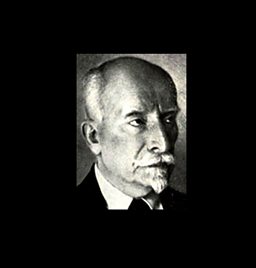

Georgia Mann delves into the world of hypnosis. How did Rachmaninov use it to write a masterpiece? What in fact happens in a session? And why do we think it's for Disney villains? Photo: Rachmaninov around 1901 when he was composing the 2nd Piano Concerto.

Explore Rachmaninov on the Â鶹ԼÅÄ

-

![]()

With Nobuyuki Tsujii (piano) and the Â鶹ԼÅÄ Philharmonic, conducted by Juanjo Mena.

-

![]()

Composer of the Week – Sergei Rachmaninov (1873-1943)

Donald Macleod explores Rachmaninov’s life in exile from Russia and attachment to the country estate he left behind: Ivanovka.

-

![]()

Proms Music Guide: Rachmaninov's 2nd Piano Concerto

In this Proms Music Guide, Suzy Klein talks about Rachmaninov's 2nd Piano Concerto.

-

![]()

Listen to a complete performance of Rachmaninov's Piano Concerto No.2

With Christian Ihle Hadland (piano) and the Â鶹ԼÅÄ Philharmonic, conducted by John StorgÃ¥rds.