What are the downsides of living our lives online?

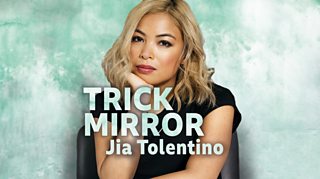

Writer, critic and editor Jia Tolentino is an essayist for the millennial generation, writing about how to exist in the 21st century, when life is increasingly lived online.

Her New York Times bestseller Trick Mirror – now a Βι¶ΉΤΌΕΔ Radio 4 serialisation – is a whip-smart, provocative book of essays. She wrote it, she says, because she is "always confused" and in these essays she writes her way to a greater clarity about the questions that trouble her, and her generation.

In this interlinked collection, Jia, a staff writer at The New Yorker and former deputy editor at the feminist website Jezebel, asks how the internet got ‘so bad’, investigates the pressures on women to attain perfection, takes a forensic and funny look at the wedding industry and, finally, argues that nowadays we are all, unavoidably, the victim of scams.

Here are four extracts from Trick Mirror.

-

![]()

Listen to Trick Mirror

Provocative, incisive essays about modern life – from the cult of weddings to the all-pervading internet.

Always Be Optimising...

An entire industry has even sprung up to give optimization a uniform: athleisure, the type of clothing you wear when you are either acting on or signaling your desire to have an optimized life. I define athleisure as exercise gear that you pay too much money for, but defined more broadly, athleisure was a $97 billion category by 2016… Athleisure, by nature, eroticizes capital. Much like stripper gear, athleisure frames the female body as a financial asset: an object that requires an initial investment and is divisible into smaller assets - the breasts, the abs, the butt - all of which are expected to appreciate in value, to continually bring back investor returns. Brutally expensive, with its thick disciplinary straps and taut peekaboo exposures, athleisure can be viewed as a sort of late-capitalist fetishwear: it is what you buy when you are compulsively gratified by the prospect of increasing your body’s performance on the market.

The 'I' in the Internet

Capitalism has no land left to cultivate but the self.

In real life, you can walk around living life and be visible to other people. But you can’t just walk around and be visible on the internet - for anyone to see you, you have to act. You have to communicate in order to maintain an internet presence. And, because the internet’s central platforms are built around personal profiles, it can seem - first at a mechanical level, and later on as an encoded instinct - like the main purpose of this communication is to make yourself look good. Online reward mechanisms beg to substitute for offline ones, and then overtake them. This is why everyone tries to look so hot and 'well-travelled' on Instagram; this is why everyone seems so smug and triumphant on Facebook; this is why, on Twitter, making a righteous political statement has come to seem, for many people, like a political good in itself.

The Story of a Generation in Seven Scams

Fyre Fest sailed down Scam Mountain with all the accumulating force and velocity of a cultural shift.

Fyre Fest sailed down Scam Mountain with all the accumulating force and velocity of a cultural shift that had, over the previous decade, subtly but permanently changed the character of the nation, making scamming - the abuse of trust for profit - seem simply like the way things were going to be. It came after the election of Donald Trump, an incontrovertible, humiliating vindication of scamming as the quintessential American ethos. It came after a big smiling wave of feminist initiatives and female entrepreneurs had convincingly framed wealth acquisition as progressive politics. It came after the rise of companies like Uber and Amazon, which broke apart the economy and then sold it a cheap ride to the duct tape store, all while promising to make the world a better and more convenient place. It came after the advent of Facebook, which drew on the renewable natural resource of our narcissism to create a world where our selves, our relationships, and our personalities were not just monetizable but actively in need of monetization. It came after college tuition sky-rocketed only to send graduates into low-wage contract work and world-historical economic inequality. It came, finally, after the 2008 financial crisis, the event that arguably kick-started the millennial-era understanding that the quickest way to win is to scam.

I Thee Dread

On the whole, though, the “traditional” wedding—meaning the traditional straight wedding—remains one of the most significant re-invocations of gender inequality that we have. There is still a drastic mismatch between the cultural script around marriage, in which a man grudgingly acquiesces to a woman salivating for a diamond, and the reality of marriage, in which men’s lives often get better and women’s lives often get worse. Married men report better mental health and live longer than single men; in contrast, married women report worse mental health, and die earlier, than single women. (These statistics do not suggest that the act of getting married is some sort of gendered hex: rather, they reflect the way that, when a man and a woman combine their unpaid domestic obligations under the aegis of tradition, the woman usually ends up doing most of the work—a fact that is greatly exacerbated by the advent of kids.) There’s an idea that women get to Scrooge-dive in heaps of money after divorce proceedings, but in fact, women who worked while married see their incomes go down by 20 percent on average after a divorce, whereas men’s incomes go up by more than that.

-

![]()

Listen to Jia Tolentino on Beyond Today

Jia Tolentino talks about the downsides and delusions of living our lives online, and how it means we are like performers who are forever on stage.

Books and reading on Radio 4

-

![]()

Book of the Week

Serialised book readings, featuring works of non-fiction, biography, autobiography, travel, diaries, essays, humour and history.

-

![]()

Audio Books

Exceptional readings, available to download to your tablet or smartphone on Βι¶ΉΤΌΕΔ Sounds.

-

![]()

A Good Read

Harriett Gilbert and her guests discuss and recommend books they have chosen.

-

![]()

Book at Bedtime

Readings from modern classics, new works by leading writers and literature from around the world.