How wellness became big business

We all know that exercise, nutritious food and low stress living are beneficial for our health. But the world of wellness has grown beyond these three essentials in recent years. With trillions of pounds a year now being spent on self-care in the name of wellness, the latest episode of Archive on 4 looks at where this phenomenon came from and what really works. Here, we explore the show’s findings and look at some evidence-based ideas for healthy living.

What does "wellness" mean?

In simple terms, "wellness" is the opposite of illness, and describes a state of being in good health. But it has come to encompass so much more than that.

Increasingly, the word has been used to reflect the idea that beyond just curing disease, we can actively work to improve our physical and mental health through things like nutrition, exercise and relaxation, so that we’re "better than well".

In the age of social media marketing, wellness (or indeed #wellness, which has been added to posts over 34 million times) has become central to the self-care phenomenon. It’s been used to describe everything from doing mindfulness meditation to taking a stress-relieving bath, or even simply treating yourself to a cashmere blanket.

The Twittersphere’s go-to physician, Dr Jen Gunter, says the concept of wellness is now used to sell so many products and gimmicks using misleading, “science-ish” language that it “means absolutely nothing”.

A quick history of wellness

The Oxford English Dictionary traces the origins of the word "wellness" back to the 1650s, but it was in the 20th century that the wellness phenomenon as we now know it began.

The Oxford English Dictionary traces the origins of the word βwellnessβ back to the 1650s, but it was in the 20th century that the wellness phenomenon as we now know it began.

One early wellness advocate was Dr Edmund Jacobson. In the 1930s, he developed a popular muscle relaxation technique that aimed to tackle tension and improve health. It’s still in use today, and is outlined in the intimidatingly titled book, You Must Relax.

In 1948, the idea of wellness was given a boost when the was created. In its mission statement, the WHO described health as not just the absence of disease, but “a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being”.

By the 1970s, Dr John Travis had founded the Wellness Resource Centre in California. He described health as “an ongoing dynamic state of growth” and aimed to empower people to help themselves. At around the same time, in-person relaxation and yoga classes took off.

With the world of wellness growing, the Berkeley Wellness Letter was launched by the University of California in 1984. It aimed to examine the science behind popular products and practices and give people evidence-based advice on what works. And it’s still going.

Today, the wellness industry is booming, fuelled by hashtagged images of self-care and healthy living shared by online influencers. At the same time, doctors are increasingly recommending free, evidence-based lifestyle changes to improve patients’ overall health.

A multi-trillion dollar industry

The wellness phenomenon is said to be worth $4.2 trillion a year, and has grown to include everything from luxury spa days to fitness classes, dietary supplements, complementary therapies and stress-relieving teas.

Ashley Oerman, deputy lifestyle director at Cosmopolitan, explains that “Wellness is just a sexier word for health. But because it’s been used to market everything from face masks to supplemental powders, basically ‘self-care’ and ‘wellness’ are just words used to sell women things that they don’t need.”

There’s even a "Wellness" collection of Barbie dolls, all dressed, accessorized and ready for relaxing activities such as meditation, spa days and fitness workouts.

Women and wellness

According to Dr Jen Gunter, there’s another way in which wellness culture affects women. She says they are often marginalised by mainstream medicine, which leaves them more at risk of misinformation and exploitation by parts of the wellness industry.

Is happiness a science?

Laurie talks to Will Davies about what we mean by "the science of happiness".

“If you’re having your pain dismissed… by sort of a patriarchal system [that] isn’t interested in your valid concerns and someone who has a very inviting presence offers you that information, of course you’re going to go there... and you get false information.”

Gunter explains that once people trust an inaccurate wellness website, they become susceptible to more misleading ideas. Many of these sites “are invested in medical conspiracy theories. And the more you’re exposed to medical conspiracy theories, the more they’re going to stick.”

Wellness meets medicine

The relationship between wellness and medicine is complicated. It’s often associated with alternative therapies that aren’t always backed by evidence. But some clinical doctors have brought these ideas into their practices too.

US paediatrician Paul Offit says many American hospitals have holistic medicine programmes – including things such as reiki and aromatherapy – running alongside traditional treatments because of the income they generate.

He thinks these approaches are OK as long as they do no harm. In fact, he says, some alternative approaches can improve mood, or boost a patient’s health by acting as “placebo medicine”.

Unproven products

Many of the products and procedures that are sold in the name of wellness don’t have solid science behind them.

Actor Gwyneth Paltrow has made waves in the world of wellness with her hugely successful lifestyle brand, , which she says is all about “optimisation of self”.

But some of the products and ideas Goop promotes have attracted criticism for their lack of a scientific or evidentiary foundation. In 2018, the company agreed to pay out $145,000 for making “unscientific claims” about jade eggs it was selling.

Goop also sells a “Psychic Vampire Repellent”, made from “sonically tuned water” and “moonlight” which promises to protect you from “psychic attack and emotional harm”.

The potential of social prescribing

When it comes to wellness, there are some things money can’t buy, like the benefits of being with other people.

A new idea that’s shown promise in early evaluations is known as "social prescribing". It involves doctors recommending that their patients attend organised activities in their community, such as dancing, coffee mornings, gardening and bingo, to support mental and physical wellbeing.

In a pilot project in Croydon, social prescribing was associated with a 20% drop in hospital outpatient referrals and a 4% fall in emergency admissions.

One doctor describes a patient he used to see often, who stopped coming to him when she took part in the scheme. “She goes to these classes, she goes on the day trips, and she’s... really well. And her blood pressure, her medical condition, is all controlled. She’s so much happier.”

Three evidence-based ideas

So, wellness doesn’t have to involve hashtags or spending a lot on the latest fads. Here are three simple suggestions for healthy living based on evidence collated by Berkeley Wellness.

β Go for regular walks. Brisk walking burns almost as many calories as a moderate run. Studies suggest it can also reduce the risk of developing high blood pressure, heart disease and diabetes, enhance brain function, improve mood and increase creativity.

β Eat a Mediterranean-style diet. Analysis of over 7,700 older adults’ eating habits suggests a balanced diet that’s rich in fruits, vegetables, whole grains, legumes, nuts, fish and olive oil supports brain function as we age. In a study of women, it’s also been associated with a lower risk of heart attack and stroke.

β Be compassionate. Although research into the benefits of being compassion is only in its early stages, there’s already some evidence that connecting kindly with others could help us feel good, become more resilient to stress and develop stronger relationships.

How to go for a walk

Walking can give you time to think or an opportunity to explore.

More from Radio 4

-

![]()

Archive on 4: The Wellness Phenomenon

Claudia Hammond explores the wellness phenomenon, from its start in California to today.

-

![]()

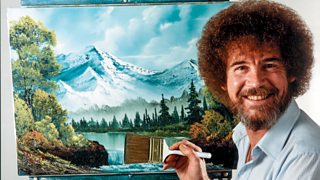

The 1980s show that is helping us feel better

How Bob Ross and his 1980s TV series, The Joy of Painting have been reducing anxiety in a new generation of viewers.

-

![]()

Seven tips for staying happy and healthy during a lockdown

Dr Beth Healey specialises in advising on staying happy and healthy in isolation.

-

![]()

Can you combine wellbeing and weight-loss?

How easy is it to revamp your lifestyle and health while still caring for your wellbeing?