Can you believe your ears?

We’re all familiar with different optical illusions. In Auditory Illusions, Trevor Cox investigates sounds that trick the ear to find out how they are used in music. Here are the five best auditory illusions and what they tell us about how the brain processes sound.

1. Shepard-Risset Glissando

This musical note seems to be forever rising in pitch, how is that possible? From one-moment to the next the sound is clearly going upwards and that is what your brain latches on to. But there is also something happening more slowly that most people miss when they first listen. The effect is like the famous Escher staircase which appears to be constantly rising but in fact is going round in circles.

The highest frequency sound is gradually dying away and disappearing. This is being replaced with a low frequency sound that gently gets louder and fades in. This creates the illusion that the sound is always rising in pitch. The illusion actually loops every ten seconds. Now you know the trick, you should be able to hear that. This effect was made famous by Hans Zimmer when it was used in the soundtrack to the film Dunkirk.

Prof Trevor Cox

Trevor Cox is Professor of Acoustic Engineering at the University of Salford, where he teaches and researches the physics of sound and the psychology of human perception.

His latest book, Now You’re Talking,β€―includes discussions of how beatboxers exploit auditory illusions.

The Shepard-Risset Glissando

This musical note seems to be forever rising in pitch, how is that possible?

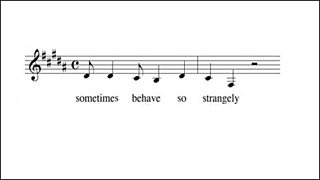

2. Speech to Song

In this illusion you’ll hear a short sentence being spoken. A short snippet is then repeated ten times.

After this, when you hear the sentence again, the woman seems to break into song mid-sentence! The speech is exactly the same – what is changing is how your brain processes the sound.

Speech inherently contains melody: as we talk, our words naturally go up and down in pitch. Sometimes this is about portraying emotion; if we are relaying bad news, the words will tend to descend in pitch. On other occasions it helps listeners understand the structure of the speech: we signal a question by raising the pitch at the end of a sentence.

In this illusion, looping a short snippet of speech ten times makes the hidden melody obvious. Once you’ve heard the snippet as song, it is very difficult to re-hear it as speech, because your brain now automatically treats it as being music. This iconic example is from psychologist Diana Deutsch, .

Further research: Diana Deutsch writes about the subject in her book,

.

3. Hidden Melodies

Listen to this extract from Christian Sindling's Frühlingsrauschen ("Rustle of Spring"). You’ll begin by hearing a jaunty melody over the top of a fast varying accompaniment. [Midi file credit: Bernd Kreuger].

Next, listen to same piece played at a quarter of the speed. The melody disappears. Where’s it gone?

As you listen to the music, the sounds from all the instruments are jumbled together as they enter your ears. Your brain needs to sort out this aural puzzle, work out which bits of sound go with which, and so make sense of the cacophony. The brain identifies and put together snippets of sound that are from the same instrument and form the melody.

When the music is being played fast, this is relatively easy. But with the slowed down music, the gaps between the notes of melody are too long for your brain to readily group them together, and so you end up losing the tune. Making sense of a complex sound scene is an immensely complicated task but it vital to hearing. Imagine picking out someone talking in a noisy pub, your brain needs to identify all the snippets of sound that comes from the person’s voice and put them together so it can work out what the person is saying.

4. Mysterious melody

Listen to this short melody. It is a famous tune that has been scrambled. Can you recognise it?

Now listen to the unscrambled version.

If you go back to the scrambled version, can you now hear the tune? (You might need to listen to both sound samples a few times for this to work).

If you look at a piano keyboard, each note (C, D, E, F, G …) appears several times across the keyboard, an octave apart. In this version all the notes were correct but the tune jumps about, with some notes an octave too high, and some an octave too low. The large leaps between the notes makes it hard to spot the melody if you don’t know what you’re listening to. But once you know what the melody should be, the brain draws on that and picks out the tune even in the scrambled version – this is an example of top-down processing, where previous experience alters how we perceive what we hear.

5. Slip, by Sarah Angliss

This piece of music was written for Βι¶ΉΤΌΕΔ Radio 4's Auditory Illusions by composer Sarah Angliss. This works best for headphones, but it also works over loudspeakers. At the start of the illusion you’ll hear some notes in one ear, then you’ll hear another set of notes in the other ear. The magic happens about 35 seconds in when these two patterns are played simultaneously. The two sets of notes merge, and two scales are revealed, one with ascending notes, and the other descending.

The piece exploits the chromatic illusion. If you run your fingers up a piano keyboard playing all the keys, you get a chromatic scale. Now, if you were to take two chromatic scales, one ascending and one descending and send alternate notes from each scale to the left and right ears via headphones, that creates the two sets of disjointed notes that you heard separately at the start of the piece.

What is surprising is that played together, the brain puts the notes back together into scales. You would think this wouldn’t happen because different parts of the scale are being played to different ears. This shows that when trying to reconstruct a sound scene, the brain sometimes makes mistakes. In this case the brain opts for putting notes together to form two neat scales, ignoring the fact they come from different ears.

-

![]()

Auditory Illusions

Trevor Cox investigates sounds that trick the ear to find out how they are used in music, and he challenges composer Sarah Angliss to write a piece inspired by those illusions.

Knowing the score on Βι¶ΉΤΌΕΔ Radio

-

![]()

Tales From the Stave

Series that tracks down the stories behind the scores of well-known pieces of music.

-

![]()

Soul Music

A series about pieces of music with a powerful emotional impact

-

![]()

Mastertapes

John Wilson talks with musicians about a career-defining album.

-

![]()

Βι¶ΉΤΌΕΔ Proms 2019 in binaural sound

Listen to immersive headphone mixes from the Βι¶ΉΤΌΕΔ Proms.