Edison was not the first to record the human voice...

It was widely believed that Thomas Edison – inventor of, among other things, the lightbulb and the motion picture camera – was the first person to record the human voice in 1888 on another of his inventions, the wax cylinder phonograph; this was the precursor of the gramophone and ushered in the age of sound recording.

However, as Radio 4's The Lost Sound Orchestra revealed, a surprising discovery made by two audio historians in 2008 re-wrote history – twice.

What we thought we knew

In 1877, Thomas Alva Edison (1847 – 1931) invented the tin foil phonograph – a machine that recorded sound by indenting a sheet of tin foil into a groove in a cylinder. A later wax version was the version on which the recordings we know today were made, including from the Handel Festival at Crystal Palace, London, in 1888. These haunting recordings were considered the earliest known audio of the human voice.

What we found out

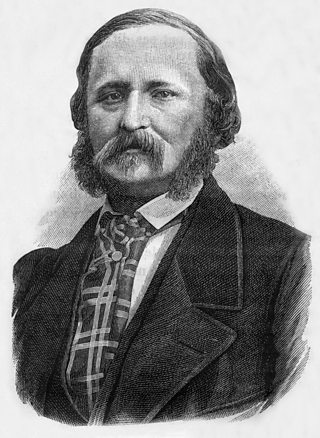

In 2008, audio historians Patrick Feaster and David Giovannoni were working together to find recordings from an even earlier sound pioneer, Édouard-Léon Scott de Martinville, a 19th-century French printer and bookseller. They travelled to Paris to look through documents about de Martinville which were being stored at the French Patent Office. They found a patent that de Martinville had logged in the 1850s for his idea for sound recording. But that wasn’t all – David discovered there were two examples of recordings, dated 1860, nearly 30 years before the Edison recordings.

Sound taken out of the air

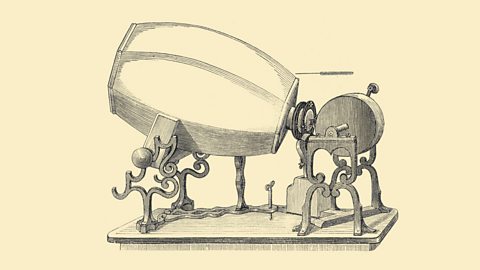

The documents found at the Patent Office suggested that de Martinville had taken airborne sounds and inscribed them onto paper. The recordings were made on a machine he called the "Phonautograph".

Patrick Feaster explains how it worked. “Take a sheet of paper and wrap it around a cylinder and then cover the paper with soot from an oil lamp. You've got this lamp burning, getting an even coating of soot on that sheet of paper. When you scratch that paper with something like hog bristle and it leaves behind a trace. Afterwards when he's made the recording, he'll take off that soot covered sheet of paper and he'll dip it in a fixative bath.”

A mystery solved?

De Martinville described his process as "natural stenography", signifying that the intention was for the marks on the phonautograph paper to be read, not played back. The challenge was to translate those marks into sound waves. David sent the papers to Patrick, back in the US, and he used a computer to do this.

"I ended up staying up all night,” says Patrick, “and adjusting them all to the same speed; by the time the sun was coming up, I was finally able to listen to that recording. It was very clearly [French folk song] Au Clair de la Lune. I was sitting there realising I am the first person to get to listen to somebody singing before the outbreak of the American Civil War – the stuff of goosebumps.”

Voices from the 1860s

A haunting song wrong-footed two historians, and a Βι¶ΉΤΌΕΔ news announcer corpsed on air...

Critical reception

The recording, described by David as “a phantasm reaching through a veiled curtain of time,” was duly unveiled to the public, with the pair thinking that it could be Scott’s daughter singing. “Wouldn’t that be sweet?” says Patrick. Not everyone reacted the way they might have anticipated, however. Charlotte Green, a Radio 4 newsreader at the time had an infectious fit of giggles when she read the item, describing it off-air as sounding like “a bee trapped in a bottle”. Others found it moving and spooky. However, no one knew that they were not hearing the whole picture, so to speak.

Encore une fois

Six months after the release of what was now recognised as the world’s first voice recording, David and Patrick were working on another audio when they had a massive realisation – the playback of Au Clair De La Lune was at double the speed! When they corrected it, the voice was not that of a young girl – it was a baritone voice and actually the voice of Scott de Martinville himself. History had to be re-written once again!

-

![]()

The Lost Sounds Orchestra

Some of the world's most weird and wonderful "lost sounds" are making a comeback. Mary-Ann Ochota meets the people who are bringing sounds of the past to life through the technology of the present.

Absorbing stories from Radio 4 in Four

-

![]()

The Curious Case of the Talking Mongoose

How a talking mongoose caused havoc at the Βι¶ΉΤΌΕΔ…

-

![]()

The scandal that rocked a village post office

The scandal reaching right to the heart of one of our cuddliest national institutions.

-

![]()

Five things a 400-year-old self-help book has taught us

How far has our insight into melancholy come in the last four centuries?

-

![]()

Ways you talk like a Viking every day

The seafaring Scandinavian invaders who transformed our grammar.