9 things we learned from a One to One with Emily Maitlis

Emily Maitlis began her career as a foreign correspondent and now hosts Βι¶ΉΤΌΕΔ’s Newsnight.

In One to One, Emma Freud talked to the journalist and newsreader about the adrenaline of the job, whether she ever experiences self-doubt – and what really drives her.

Here are nine things we learned about the queen of TV current affairs.

1. She came close to giving up

When she was starting out, Emily’s career was far from plain sailing. “I was a terrible reporter,” she admits. “The only advantage was I made all my mistakes in a place and at a time where I didn’t know anyone, but I literally made every mistake in the book.” She recalls the tape running out at a crucial moment during an interview with a senior politician, and leaving her microphone on the bus as she travelled to the Chinese border. “Every day was a disaster,” she says. The reporter also remembers filing a piece about a new shopping centre, when her employer was anticipating a hard-hitting political interview with the governor of Hong Kong. “It took me so long, ridiculously long, to learn that stuff,” she says. “So many times I nearly gave up and I got really down about it and thought I was just not made for it,” says the journalist.

2. Showing sympathy as a reporter helps the audience to trust you

“I think you go into a debate trying to be fair minded and trying to be balanced but occasionally there will be a sense where it feels like the moral imperative is pulling you one direction or another,” says Emily. With time she has learned that it’s ok to be guided by that. “If I stuck to rigid guidelines and said ‘it’s not good and it’s not bad, it’s not this and it’s not that,’ people actually wouldn’t trust me as much.”

3. There isn’t a perfect interview formula

“We’re not robots,” says Emily. “There isn’t a perfect formula for an interview and there are days when you bring too much of you and there are days, quite honestly, when you don’t bring enough of you.” Often, with hindsight, she recognises that she “should have gone in with a bit more emotion… because that’s sometimes the moment at which the audience engages with the actual conversation.”

4. She wants to break down robotic communication

There is more than one reason why she has given her life over to news. “Part of it is genuinely selfish,” says the journalist, “It fascinates me.” But there is another, deeper motivation: “I hope somewhere to break down what seems to be a kind of robotic communication between those in power and those who are understanding power.” We’re all so “flippant” and “slogan driven,” says the newsreader, but being a journalist enables you to “make people think about their words.”

I don’t want to hear myself saying, or endorsing, platitudes.

5. She has a real horror of the platitude

Political manifestos that contain things like “forwards not backwards” or “on and together” or “fairer for all” fall down when you try and imagine the inverse of those statements, says the journalist. “Would you ever say ‘backwards not forwards’? Would you ever say ‘not fairer for all’ or ‘more unjust for everyone’? They’re such platitudes and I think I have a real horror of the platitude,” she states. “I don’t want to hear myself saying them, I don’t want to hear myself endorsing them, I don’t want other people to say them to me, and to just be able to get away with them.” She says, “I just want to unearth what people actually mean.”

6. She won’t take the moral high ground

Although she’s driven by exposing hypocrisy, she doesn’t see herself as morally superior: “I’m not a priest, and I don’t want to actually think of any moral high ground where I’m saying ‘I’ve got this and you haven’t’, because that’s a really dangerous place for a journalist to be.” She’s all in for the glass-houses-and-stones idiom. “It’s quite easy to cast our politicians and our leaders into roles where they’re all hypocrites, or they’re all traitors,” says Emily, “but actually it’s a bloody awful job and I wouldn’t touch it with a barge pole… I’m actually incredibly grateful for anyone who wants to be part of that democratic system of government.”

7. She is powered by adrenaline

Emily admits that the job is addictive. “Every time you’re standing in the pouring rain, at a scene of horror, with everything crashing around you,” it’s easy to say you’re never, ever doing this again, says the journalist. But then you have a night’s sleep and you’re suddenly “itchy and mooching round the house waiting for the next bit of adrenaline… I think I’m incredibly powered by adrenaline and I don’t always admit that to myself,” says the reporter.

8. She only ever feels as good as her last interview

Another aspect that makes the job compulsive, which Emily hates more than anything, is that “you only ever feel as good as your last interview.” She finds herself looking back on her work in previous years, drawing unhelpful comparisons and berating herself. “You do it the whole time,” she admits, “it never quite goes away.” She compares it to how an athlete functions: you have a “personal best” and as soon as you’ve left that behind, you’re thinking about the next event.

9. She longs for stories to be less impactful

“On some level I must go towards stress”, says the newsreader. But that doesn’t mean she wants news events to be bad. When she was covering the Grenfell Tower tragedy there was a 13-year-old girl who had gone missing and they ended the broadcast by thinking she’d been found. “All I wanted to do that night was offer, in the midst of all the kind of horror and upset, I wanted to feel that I’d ended that night by one piece of redeemingly good news,” says Emily. Rather than developing an eagerness for high death tolls and dramatic crises, she believes the opposite has happened: “I long for stories to be less impactful.”

Listen to, or download Emma Freud's One to One interview with Emily Maitlis at Βι¶ΉΤΌΕΔ Sounds.

Revealing personalities on Radio 4

-

![]()

One to One

Broadcasters follow their personal passions by talking to the people whose stories interest them most.

-

![]()

Desert Island Discs

Eight tracks, a book and a luxury: what would you take to a desert island? Guests share the soundtrack of their lives.

-

![]()

Chain Reaction

A sequence of programmes in which public figures choose others to interview.

-

![]()

Great Lives

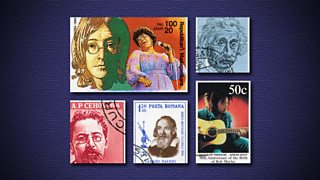

Biographical series in which guests choose someone who has inspired their lives.