Chilling tales: Why is science fiction obsessed with eternal life?

18 March 2019

In Me, My Selfie and I, artist Ryan Gander explores what technology is doing to our sense of self. In Arizona, the CEO of a cryonics facility - where people pay six-figure sums to have their bodies deep-frozen after death - tells him he’ll celebrate when he is resurrected in the future; but what then? We look at how writers and filmmakers have dealt with the upsides and downsides of immortality.

At Alcor Life Extension Corp's cryonics facility in Arizona, bodies are preserved in liquid nitrogen for $200,000; head-only processing and storage is a snip at $80,000. Ryan Gander describes the lab in his ΒιΆΉΤΌΕΔ Four programme Me, My Selfie and I as "looking like Star Trek". Alcor's CEO, the charismatic Max More, can't wait to 'wake up' in the next century.

With around 200 individuals currently preserved, and many Silicon Valley executives on a waiting list of 1,000, Alcor is part of a small but growing international industry that began in 1967. And the concept of preserving the human body at the point of death, in order to bring it back to life in the future, has long captured the imagination of writers and filmmakers.

Cryonic preservation has been used in many stories to facilitate time travel into the future

Freezing is science fiction's most popular means of achieving suspended animation. Cryonic preservation has been used in many stories to facilitate time travel into the future, and is a common device in stories of slower-than-light spaceships, from 2001: A Space Odyssey to the Alien series.

But the central premise of cryonics has actually been around a lot longer than you might think. Francis Bacon, the 16-17th century philosopher and pioneer of the scientific method, was interested in how life could be preserved. John Aubrey's Brief Lives (late 17th century) relates the story of Bacon's death: on a winter night he procured a chicken, killed it and stuffed it full of snow in the hope of preserving it, convinced that this was the key to preserving life, or at least organic matter. In the process, he caught pneumonia and died.

In fiction and film, immortality is often treated as a curse, and there are many examples of embittered souls struggling with their lot. But regardless, human culture continues its compelling, addictive interest in the idea of living forever.

The origins of cryonics

In 1962, Robert Ettinger published The Prospect of Immortality, the book that gave birth to the term ‘cryonics’ – the process of freezing a human body after death in the hope that scientific advances might one day restore life.

He wrote: "Clearly, the freezer is more attractive than the grave, even if one has doubts about the future capabilities of science. With bad luck, the frozen people will simply remain dead, as they would have in the grave.

"But with good luck, the manifest destiny of science will be realised, and the resuscitees will drink the wine of centuries unborn. The likely prize is so enormous that even slender odds would be worth embracing."

Forever is a long time to be the wrong age

Eternal youth sounds wonderful, but what if you become immortal at the wrong age? In (1726), Jonathan Swift explored this sobering thought. On the Island of Immortals, the Struldbrugs of Luggnagg are stripped of legal rights at 80 but continue to live forever, getting older, becoming helpless and senile, and are generally pretty unhappy. In Swift's words, "they were the most mortifying sight I ever beheld".

On the other hand, life as a permanent child might not be a bed of roses either. Fahrenheit 451 author Ray Bradbury’s tragic short story (1948) features an immortal who stops ageing when he is 12. He finds a sort of role as a foster child to lonely couples. In Bradbury's wise words, "science is no more than an investigation of a miracle we can never explain and art is an interpretation of that miracle."

The long dark tea-time of the soul

In Douglas Adams’ 1978 The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy series, Wowbagger the Infinitely Prolonged, who became immortal through an unfortunate workplace accident, finds himself living through endless time with very little to do.

Adams wrote: “In the end it was Sunday afternoons that he couldn’t cope with, and that terrible listlessness which starts to set in at about 2:55pm... as you stare at the clock the hands will move relentlessly on to four o’clock, and you will enter the long dark teatime of the soul.”

Wowbagger occupies himself instead by embarking on a quest to insult everyone in the universe, in alphabetical order.

Jorge Luis Borges’ short story (1947) introduces a City of Immortals, the inhabitants of which are virtually immobile through lack of drive and boredom. The central character meets the great poet ΒιΆΉΤΌΕΔr, now a cave dweller who sits like a rock all day, who says that it would be more difficult not to have written The Odyssey and The Iliad, given infinite time.

Forever friends?

A major drawback of immortality is that your all your friends will die and you'll be alone in the world. But if you're in luck there will be other immortals with whom to share the good times. In cult film (1986) the prophecy that “there can be only one” means that Christopher Lambert, Sean Connery and the rest of the wandering immortals are engaged in trying not to have their heads forcibly removed by The Kurgan's sword, accompanied by Queen's song Who Wants To Live Forever?

In the opera The Makropulos Affair (1925) by Czech composer Leoš JanáΔek, the character Elina Makropulos drinks an elixir conferring eternal life, but in 300-year stages. After the first 300 years she opts for normal life. The original play was used in a by philosopher Bernard Williams in which he argued that, over the course of an immortal existence, all of what philosophers call categorical desires will be sated and life will be sapped of its motivational vim. Inevitably the immortal will end up bored and apathetic, just like Elina.

The Makropulos Affair is based on the play by Czech writer Karel Capek, who in 1920 coined the term 'robot' in R.U.R. or Rossum's Universal Robots. R.U.R. was also the first televised science fiction broadcast, .

Innocence lost

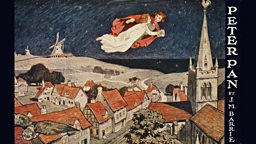

“All children, except one, grow up.” When J.M. Barrie wrote that about in 1911, it was seen as the expression of a beautiful and melancholy fantasy. But the idea of a child who never grows up isn't necessarily innocent, and recent reimaginings have tended to transform Peter into a bit of a villain.

it’s quite easy to do when, in the book and in the play, Peter murders pirates seemingly without a care. In the book, Peter also kills the Lost Boys, either to “thin the herd” or because they are breaking the rules by growing up.

These characters all serve to point up that immortality isn't all it's cracked up to be; that our minds couldn't handle the reality of it. The unfathomable work of a higher intelligence can move immortality into another realm, as director Stanley Kubrick attempted in 2001: A Space Odyssey.

In a 1969 interview Kubrick said, "the God concept is at the heart of this film... you realise that the religious implications are inevitable, because all the essential attributes of such extraterrestrial intelligences are the attributes we give to God."

Beyond the infinite

In 2001: A Space Odyssey, several of the astronauts on the mission to Jupiter are kept alive in a state of cold storage or suspended animation. It's a standard device in classic science fiction, from to the Alien franchise, and is an area of .

2001: A Space Odyssey confronts humans' philosophical and metaphysical impulses

But 2001 confronts humans' philosophical and metaphysical impulses in its closing scenes, which are more explicitly detailed in Arthur C Clarke's novella than in the film. what happens in the plot, saying the response to is up to the individual:

"When the surviving astronaut, Bowman, ultimately reaches Jupiter, this artifact sweeps him into a force field or star gate that hurls him on a journey through inner and outer space and finally transports him to another part of the galaxy, where he's placed in a human zoo approximating a hospital terrestrial environment drawn out of his own dreams and imagination.

"In a timeless state, his life passes from middle age to senescence to death. He is reborn, an enhanced being, a star child, an angel, a superman, if you like, and returns to earth prepared for the next leap forward of man's evolutionary destiny."

Watch the documentary

-

![]()

Me, My Selfie and I with Ryan Gander

Watch on ΒιΆΉΤΌΕΔ Four at 21:00 on Monday 18 March, and then on ΒιΆΉΤΌΕΔ iPlayer.

More from ΒιΆΉΤΌΕΔ Arts

-

![]()

Picassoβs ex-factor

Who are the six women who shaped his life and work?

-

![]()

Quiz: Picasso or pixel?

Can you separate the AI fakes from genuine paintings by Pablo Picasso?

-

![]()

Frida: Fiery, fierce and passionate

The extraordinary life of Mexican artist Frida Kahlo, in her own words

-

![]()

Proms 2023: The best bits

From Yuja Wang to Northern Soul, handpicked stand-out moments from this year's Proms