On the money - how Shakespeare became legal tender

When it comes to writing plays William Shakespeare was always on the money. And that was never more true than in 1970 when the playwright became the first non-Royal, apart from Britannia, to appear on UK legal tender, on the reverse of a £20 note.

His image was by the Bank of England's first full-time banknote designer Harry Norman Eccleston and from 18 April 2016 it will take centre stage in a display at the Bank of England Museum investigating the design of the £20 series D Shakespeare banknote. Here Anna Spender, Curator of the Bank of England Museum explains its history.

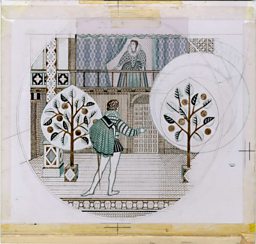

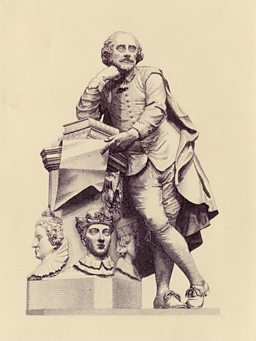

To mark the 400th anniversary of Shakespeare’s death, this display will explore the individual design elements used in the iconic £20 note first issued in July 1970, reflecting the cultural significance of the playwright and his work. Over the years Shakespeare’s image and his plays have been used in popular culture as a way of capturing the attention of the general public; whether it be in education, press, theatre, television, tourism or indeed our currency. This display will explore the work of banknote designer Harry Norman Eccleston from his rendering of the renowned William Kent statue to his master drawing of the balcony scene from Romeo and Juliet.

The £20 note – the oldest printed denomination

When the Bank of England was founded in 1694, and for the first thirty years of its existence, all banknotes issued were for handwritten amounts reflecting the quantity of gold deposited by the customer – the actual amount of the note was added in manuscript by the cashier. Notes for fixed sums were not issued until 1725. In that year the £20 note was the first of fourteen printed denominations (ranging up to £1000) to be issued.

In 1943 the authorities announced that all denominations above £5 would cease issue, in order to counter the problem of hoarding and the threat of forgery

The first £20 notes, like all banknotes, were printed in black on white watermarked paper – there were no designs on the reverse. Although the Bank experimented with new designs and colour printing, its notes remained essentially the same during the nineteenth century. In 1855 the Bank switched from intaglio (engraved design) to letterpress (printing from raised type) and adopted a revised Britannia design. From 1855 the traditional white £20 note remained virtually unaltered until its eventual withdrawal in 1943.

In 1943 the authorities announced that all denominations above £5 would cease issue, in order to counter the problem of hoarding and the threat of forgery (particularly following the German counterfeits of Operation Bernhard during the Second World War). The issuing of £20 notes was resumed 27 years later, following the popularity of the £10 series C banknote introduced in 1964 after a 21 year absence.

Designing the Shakespeare banknote

Harry Eccleston’s £20 series D banknote, issued in 1970, was the first £20 note available since 1943. Eccleston was the Bank's first full-time banknote designer, a position that was created for him in 1967. He had been at the Bank since 1958 as artistic designer at the printing works, and remained in his new post until 1983. In 1979, he was appointed OBE.

Eccleston estimated he had spent about six months working on the design initially

The note was described as a ‘breakthrough’ by The Times newspaper having been designed by a member of the Bank’s staff and portraying a figure other than the Queen or Britannia. Each banknote design is the subject of a research project covering almost every aspect of the personality’s life and achievements.

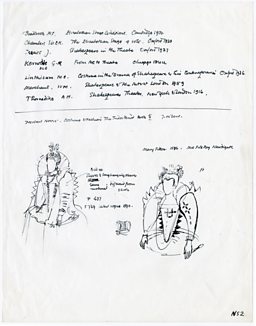

Eccleston estimated he had spent about six months working on the design initially, half in research and half in preparing the master drawings. In an interview for the internal magazine for the Bank’s printing works, Britannia Quarterly, in Winter 1987 Eccleston explained that whilst designing the Shakespeare £20 note he found ‘lots of material, so I read about him; I visited Stratford-on-Avon; I looked at prints and paintings, sketches and portraits; I read books about him; I even saw the odd Shakespeare play!... Research and design are almost inseparable.’

The canvas is ridiculously tiny and there is no 'frame' to your picture – the edge is more of a wavy line. Add to that all the words you are obliged to include for statutory purposes, and then the restrictions that printing from an engraved plate imposes upon the monarch's portrait ... On top of all that, the design has to be capable of mass production on high-speed presses so that notes printed years apart look identical when placed side by side.

Harry Eccleston in an interview for The Moneymakers International (1989) about designing the series D banknote

The £20 denomination – the first in the new pictorial series D – featured a new portrait of the Queen (the first royal portrait to appear on a £20 note) and a vignette of St George and the Dragon based on the ‘Lesser George’ badge of the Order of the Garter at the Victoria and Albert Museum. The reverse showed the statue of William Shakespeare designed by William Kent from the memorial in Westminster Abbey adjacent to the balcony scene from Romeo and Juliet.

Shakespeare and Romeo and Juliet

In March 1968 the Design Committee was shown Eccleston’s suggestions for the £20 note. The proposed subject was Shakespeare and the choices lay between using the William Marshall portrait (created for John Benson's 1640 edition of Shakespeare’s poems) or the memorial statue in Westminster Abbey by William Kent. The accompanying vignette would be a scene, or ‘episode’, from Midsummer Night’s Dream, Henry V, Merry Wives of Windsor, or Romeo and Juliet.

Eccleston urged the Committee to consider the ‘episode’ in conjunction with the portrait of Shakespeare. He suggested that using Henry V with the Kent statue would be ‘unthinkable’ as the statue was ‘in a much more romantic idiom.’ The Committee agreed that a scene from Henry V would be too rigid and by May 1968, with the approval of Governor Leslie O’Brien, decided on the ‘romantic’ image of Kent’s statue alongside a scene from one of the most powerful love stories of all time - Romeo and Juliet.

Eccleston’s drawing of Westminster Abbey’s William Kent statue on the reverse of the £20 note can be seen as a way of illustrating the values of patriotism, strength and security. Shakespeare’s cultural legacy increased the physical worth of the note. The banknote’s high denomination, introduced after a 27 year absence, presented an equally high value to the image of the playwright.

The security of the Bank of England can be represented physically through the marble solidity of Kent’s statue of Shakespeare, and can be characterised symbolically through his works. This imagery, together with the gravitas offered by Westminster Abbey, created an institutional alliance linking the strength of the currency with the influence of tradition.

‘Faraday upstages the Bard’

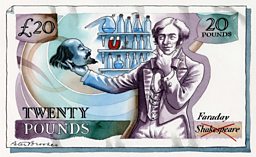

On 5 June 1991 Shakespeare was replaced by Michael Faraday as the new character for the £20 series E note amid headlines such as ‘Faraday upstages the Bard’ (The Daily Telegraph), and ‘Bard off the bill’ (Financial Times). The Times cartoonist, Peter Brookes, drew a mock £20 reverse, depicting Faraday holding Shakespeare’s head contemplatively, like Hamlet with the skull of Yorick.

The future of the £20 note

Since Shakespeare, we have seen Michael Faraday, Edward Elgar and currently Adam Smith on our £20 notes. In September 2016 the Bank of England will be printing banknotes on polymer, beginning with the £5 note featuring Sir Winston Churchill.

The next £20 banknote will celebrate Britain’s achievements in the visual arts

The £10 note, featuring Jane Austen, will be issued in 2017 and the £20 note by 2020. Polymer banknotes are cleaner, more secure, and more durable than paper banknotes. They will provide enhanced counterfeit resilience, and increase the quality of banknotes in circulation.

The next £20 banknote will celebrate Britain’s achievements in the visual arts. Between 19 May and 19 July 2015, the public were asked to nominate a visual artist to feature on the note. The final character will be announced in spring 2016 and the note will enter circulation by 2020. For more information about the move to polymer please visit the Bank of England .

The Bank of England has featured characters on our banknotes since 1970, with Shakespeare given the distinguished position of being the first historical personality to appear. His fellow £20 banknote characters follow the Bank’s tradition celebrating individuals that have shaped British thought, innovation, leadership, values and society.

While Shakespeare’s image was once mechanically reproduced into millions of identical representations on banknotes, the playwright’s talent will remain unique and unparalleled.

Visitor information

Eccleston’s Shakespeare is at the Bank of England Museum from 18 April. Entrance is free. For information on opening hours and where to find it, visit the Bank of England Museum , call 020 7601 5545, or email museum@bankofengland.co.uk

More on Shakespeare:

-

![]()

An international online festival for UK and global audiences to experience a remarkable collection showcasing the creative range of the Bard’s work

-

![]()

A collection of TV, radio and online broadcasts from around the Â鶹ԼÅÄ celebrating the 400th anniversary of arguably the greatest ever playwright

-

![]()

When Shakespeare died, he famously left his wife only one thing, but new analysis of his will claims this was an act of love from a dying man