What Willβs will tells us about Shakespeare

When William Shakespeare died he famously left his wife Anne only one thing: their 'second best bed'. But new infra-red analysis on Will's will claims this was far from a snub, but an act of love from a man who knew he was dying.

The new scientific analysis on the historic last will and testament is helping paint a vivid picture of the personality of the playwright, and just what he thought of his family.

Scientific research by , never before carried out on the will, has revealed Shakespeare as a canny businessman keen to secure a financial legacy for his family.

The initial results from the analysis will force scholars to reassess many of the existing assumptions about Shakespeareβs family life and death...

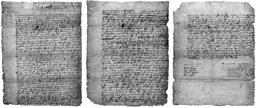

Paper and ink analysis of the 400-year-old document shows page two of the three-page manuscript was drafted at a different time to the first and last pages with significant changes made in both January and March 1616 as his - and his family’s - status changed.

The initial results from the analysis will force scholars to reassess many of the existing assumptions about Shakespeare’s family life and death and casts serious doubt over several accepted theories which include:

- Shakespeare had been ill for some time and had retired to Stratford where he wrote his will as he lay dying

- he was sour and cold to his family and left them no tender words in his last will and testament

- he distrusted his daughter Judith and her new husband Thomas Quiney and changed his will to stop Quiney from benefiting

- he was mean or indifferent to his wife Anne by only leaving her the “second-best bed”

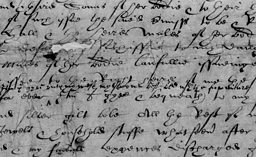

Shakespeare's will (page 1)

Conservators at The National Archives treated the will over a four-month period from September 2015 to January 2016, by removing a heavy paper backing and some earlier repairs made with silk, to return the document’s appearance to closer to its original state. This allowed close analysis of the paper using x-ray technology and near infrared light for the first time. Experts at the British Library then carried out multi-spectral imaging of the will, exposing the manuscript to ultraviolet, visible and infrared rays as a specialised camera captured images not visible to the human eye.

It may be that page two of the will is the surviving portion of this 1613 version...

The results indicate that page two was drafted at a different time to pages one and three, disproving the theory the will was written in one sitting.

The National Archives’ Legal Records Specialist Dr Amanda Bevan believes page two to be the surviving section of an earlier will. Page one of the will was dated January 1616 before being crossed out and replaced with March. Some scholars had believed the will had been copied out in its entirety in March 1616 with the clerk copying out “January” in error. However, the latest imaging indicates this was not the case and that page one was indeed written in January 1616 and then updated with corrections and additions in March 1616 – one month before Shakespeare died.

The ink used to replace January with March appears to be the same as ink used to make several alterations to the will; including the addition of leaving his “second best bed” to his wife Anne.

Dr Amanda Bevan, Legal Records Specialist at The National Archives has re-examined the will from a legal standpoint and used the latest scientific research to offer new explanations for additions and changes.

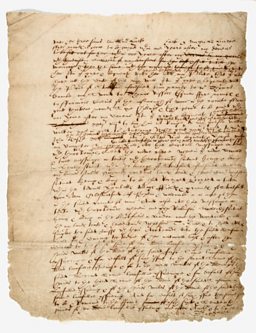

Shakespeare's will (page 2)

"In March 1613 Shakespeare bought the Blackfriars Gatehouse property in London, in trust, and we think he wrote a will then to instruct his trustees. It may be that page two of the will is the surviving portion of this 1613 version as it sets out the bequests to his daughter Susanna of his lands; including the Gatehouse. These did not need to be changed in January 1616 when he revisited his will, I believe, to account for the fact his daughter Judith was to be married to Thomas Quiney.

Page one outlines the bequests of money to Judith in preparation for this upcoming marriage. The earlier will was written in anticipation of a potential future marriage with three lines surviving, crossed out, on the top of page two. You can also see the writing on the bottom of page one seems to be squeezed in to fit on the page. In January 1616, Judith’s marriage was imminent and her father decided he could afford to be more generous and also look to establish a financial legacy for their future children.

I believe page three was also rewritten in January 1616, possibly to get the whole will re-witnessed. Some people think the corrections and additions were mistakes or afterthoughts but as we can now date some of these to March 1616 it makes these last minute gifts more poignant. He may have known he was dying in March and added these personal items for family and friends to what had been up until that point a very business-like document. The second best bed was certainly not a slight on Anne as the best bed would have stayed with his house."

Although the results of the scientific analysis are still being examined, another early interpretation that can be drawn is that Shakespeare kept his will as a living document for updating when his, or his family’s, circumstances changed.

Shakespeare's will (page 3)

Dr Katy Mair, Early Modern Records Specialist at The National Archives adds:

It appears he was concerned about his financial legacy and that of his family throughout his life.

“You often hear it said that we don’t know much about Shakespeare; the personality behind the plays. This is just not true. The National Archives holds more than 100 documents relating to his life, both in Stratford and in London.

“This latest research adds significantly to our knowledge by revising our understanding of his will. It has been argued that he retired to Stratford as he was gravely ill but he was clearly staying engaged with business matters and other documents held at The National Archives support this theory. It appears he was concerned about his financial legacy and that of his family throughout his life, as shown by the redrafting of his will.

“Shakespeare was a savvy businessman as well as a successful playwright and initial findings from this new research will continue to help shape our understanding of the man.”

Dr Cordelia Rogerson, Head of Conservation at the British Library explains more about the process involved in making these exciting new discoveries:

Shakespeare's will is an excellent example of the possibilities of multi spectral imaging.

"Multi-spectral imaging is a powerful technique we use in the British Library conservation centre to apply to manuscripts revealing erased text, under drawings and subtle differences in material composition, as was the case with Shakespeare's will.

It is a non-destructive technique that captures data across the electromagnetic spectrum. Not limited to the visible frequency, it works from ultraviolet to infrared wavelengths meaning the final composite image can capture details not visible to the naked eye. An entire object or just selected parts can be imaged.

We cannot always predict what will be discovered but Shakespeare's will is an excellent example of the possibilities of multi spectral imaging allowing new interpretations and understanding of how a manuscript was created."

This April marks the 400th anniversary of Shakespeare’s death and the will is currently on display at By me William Shakespeare: A life in writing, a unique collaboration between The National Archives and King’s College London, at the Inigo Rooms, Somerset House East Wing.

Conservation of Shakespeare's will

Find out more

Shakespeareβs will timeline

- c. March 1613: Shakespeare acquires the Blackfriars Gatehouse and may have drafted his will around this time.

- January 1616: Shakespeare re-drafts his will including provision for his daughter Judith’s upcoming marriage.

- March 1616: Some personal bequests, including the second best bed, are added to the January version of the will.

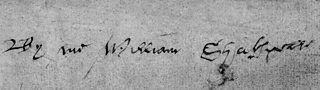

By me William Shakespeare: A life in writing

By me William Shakespeare A life in writing is a first joint exhibition from The National Archives and King’s College London and brings nine key Shakespeare documents together for the first time to provide a unique journey into Shakespeare’s life in London. It provides a once in a generation opportunity to see documents and objects together, including Shakespeare’s last will and testament and four of his six known signatures.

Exhibition Opening Times: Monday to Sunday, 10am-6pm; Thursday 12pm-8pm at the Inigo Rooms, Somerset House East Wing.

Shakespeare on Tour

Discover stories of Shakespeare performances across England from the 16th Century to the present day.

From the experts:

-

![]()

Where did the term 'bardolatry' come from?

-

![]()

Sarah Siddons helped legitimise the role of female performers

-

![]()

Ira Aldridge toured extensively during the 19th Century