How one woman had her face rebuilt 17 times

In the ΒιΆΉΤΌΕΔ Radio 4's Life Changing, Jane Garvey talks to remarkable people with extraordinary stories. She discovers the transformative moment that has reshaped their life in surprising ways.

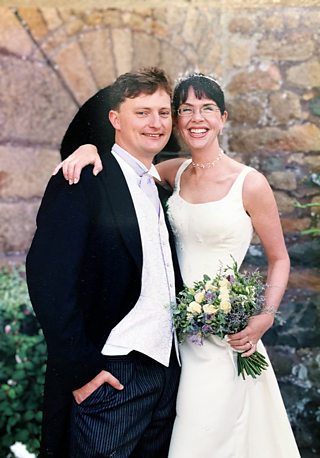

For Jill Clark, one trip to the pub 25 years ago would change her life – and face – forever. She explains how she was able to rebuild both, and now campaigns for “face equality” for those who look facially different.

Photos courtesy Jill Clark ©

βI remember getting on the boat to come back to Guernsey, and I donβt remember anything else.β

Jill grew up in Chester and met her future husband, Russell, at university in Hull. When they had both graduated, Jill decided to move to Guernsey with him.

It was 1996 and Jill was just 24. “It was the end of the summer and we were making the most of the good weather,” she recalls. With a group of friends, they went by boat to a tiny island just off Guernsey for dinner at the pub before travelling home.

That is where her memory of the night ends: “I remember getting on the boat to come back to Guernsey, and I don’t remember anything else.”

“I woke up in hospital very, very confused”

The event that Jill is unable to recall was life-changing, and left her fighting for survival. A speedboat, driven too fast, slammed into the side of the boat where she was sitting. The anchor fixed on the front of the speedboat struck her in the face.

She woke up in Southampton General Hospital, unable to talk because she had a tube through her throat to help her breathe, and unable to see because her face was swollen and bandaged.

“I had a pad of paper and a pen and the first thing I did was just draw this question mark because I just didn’t know what was going on.”

βI was in surgery for 17 hours when they originally put me back togetherβ

Immediately after the accident, Jill was operated on for hours.

She was warned that her appearance was going to be radically different due to extensive soft tissue damage, and impact to her nose. “Because the anchor had hit me in my nose, I effectively didn’t really have a nose anymore,” says Jill.

But losing it kept her alive. “My nose saved me,” says Jill. It had effectively acted like an airbag. “Because my nose had taken all the force, it had then shattered my nose and shattered my eye orbits and shattered my forehead. But if the boat had hit me an inch above, it would have gone through my brain; an inch below it would have gone through my mouth, or an inch either side and it would have gone through my eye and I would have probably not survived.”

“So, I was sitting in the wrong place, but I was actually sitting in the right place on the boat.” She says she is “amazingly fortunate” to be alive.

βI think I was a little bit deludedβ

Despite her injuries, Jill remained positive. She thought she would be in hospital for a couple of weeks and then things would return to normal. “I think I was a little bit deluded in that I thought that I would just get better really quickly and everything would be fine.”

But when friends and family came to visit her, she began to realise the extent of the damage. “There is that slight intake of breath when somebody sees you. So I did know that my appearance was quite shocking at that stage.”

“I couldn’t actually see myself for a few weeks because my eyes were very badly damaged,” she recalls. But once the swelling had gone down there was a “big reveal”. The bandages were taken off and – with her surgeon, parents and Russell by her bedside – she was handed a mirror. “It was kind of exciting but it was really, really shocking at the same time. I just didn’t look like me. It was someone else’s face.”

“We took all the mirrors down”

After a month in hospital, Jill returned to Guernsey and the one-bedroom flat she shared with Russell. It was there that the extent of her face-altering injuries hit home.

“I was very, very swollen. My eyes were lopsided. Probably the biggest issue was that I had almost no nose,” says Jill.

“I found it really hard to go out and I found it really hard to look at my appearance, so we took all the mirrors down,” she recounts. “I was just sitting in this flat – this one bedroom, tiny flat – on my own, watching repeats of TV.”

“I started to think, this is really bad. I’ve got to just snap out of this. I’ve got to stop sitting on the sofa, feeling sorry for myself… I think it was all too much to go out and face the world, and people see me. It was really hard. That was the low point.”

“I walked into the pub and everyone was amazing”

Before the accident, Jill and Russell used to go to the same pub every Friday night. Russell convinced her that they should venture there as normal. “I walked into the pub and everybody was amazing,” says Jill. “Absolutely amazing.”

Elsewhere, she had a range of responses: “I had some people staring. I had some people who would literally just walk up to me and say ‘Goodness me what’s happened to you?’ I had a lot of quite pitying remarks: ‘Oh dear, you look so awful, this must be so awful for you.’ They were probably the hardest,” she says. Many people presumed that because her face wasn’t “normal” she must have a “dreadful life.”

βI had seventeen operations on my face and my eyesβ

“It was a long road to recovery but the surgeons who dealt with me in Southampton were just amazing,” says Jill. “They literally rebuilt my skull… I had seventeen operations on my face and my eyes.”

Jill had bone taken out of her hip to help reconstruct her missing nose. The biggest operation involved putting a titanium plate into her forehead. And there were more procedures to try and make her face more symmetrical. Then, in 2001, Jill decided to draw a line under it all. “It got to the point where I just thought, why am I being pressured to have more surgery to look more perfect, when actually I didn’t really want it anymore?”

“It was all about being perfect,” she says. “My eyes are quite lopsided and one eye doesn’t close very well and I just thought, I could go through more surgery and more trips to Southampton and more time off work, or I could just actually accept that this is the way I look and stop striving to be how I was before.”

Changing Faces

Jill was getting used to life with her new appearance when she met James Partridge, the founder of the Changing Faces charity, focused on supporting people who look visually different. James (who died in 2020) had suffered severe burns in a car crash when he was a teenager and had significant changes to his appearance.

“I met him at the airport and I went up and introduced myself and we started talking and he was just incredibly inspirational,” says Jill. “He was 100% positive about everything and he was not going to let his changed appearance impact the quality of his life at all, and spent all his life campaigning for people not to judge people on their appearance.”

“He’s really, really made a difference to me in terms of putting my accident and the way I looked into perspective,” says Jill. He encouraged her to use what had happened to her in a positive way and prove to people that despite looking different, and not having a “perfect” face, she could still be really successful.

"He spent all his life campaigning for people not to judge people on their appearance"

How meeting James Partridge helped Jill Clark come to terms with her "imperfect" face.

(above) Russell, Jill and Jill's brother brother Andrew raised £10,000 running the London Marathon for Changing Faces in 2013.

“66 million people in the world have got a significant facial difference”

Jill admits that not everyone with facial differences is able to stay positive. “And there’s nothing wrong with them, they look different; what is wrong is everyone else’s reaction to them.”

“It’s human nature to judge somebody and to look at somebody and to assess their appearance, but we need to overcome that gut urge to stare at somebody or make a comment, and we need to focus on the person and not the way they look,” Jill states.

It could be any one of us. There are people who are born with facial differences; there are people who are left scarred from accidents; there are people who have cancer and have to have surgery on their face. “I think the latest estimates are that it’s one in 111 people so that works out as 66 million people in the world who have got a significant facial difference that causes them to be treated differently.”

βSociety is all about having perfect features and looking perfectβ

Unfortunately, says Jill, society is moving in the wrong direction. “Society is all about having perfect features and looking perfect, which means that it’s even more likely that people don’t want to be near somebody who doesn’t look perfect,” she says.

Most peopleβs photographs online are doctored to make them look even more perfect than they areβ¦

As a mother of adolescents, she’s all too aware of the pressures that social media present. “There is this obsession of appearance, particularly when you’re younger, and it’s this constant aiming for this perfect image. And it’s just not attainable. Most people’s photographs online are doctored to make them look even more perfect than they are… I really feel for the younger generation nowadays with social media because the pressures on them to look perfect are much, much harder than they were when I was young.”

She says parents have to be better role models: “It’s really important that parents do not make comments about people’s appearance in a negative way because the children will copy them.”

“We’re trying to get equality for people who look facially different”

Jill is pleased that she’s been able to put her experiences to good use.

James had always wanted to set up an umbrella charity that brought together all of the charities and NGOs all over the world that fight for people with facial differences and so he founded, with Jill’s help, Face Equality International.

“We now have nearly 50 charities worldwide who are campaigning and supporting people with a facial difference,” says Jill, who is now Chairman of the charity. “We’re trying to make waves and we’re trying to campaign and we’re trying to get equality for people who look facially different.”

“If I can keep working on that and keep supporting that then I’ll be very happy.”

-

![]()

Life Changing β subscribe and listen on ΒιΆΉΤΌΕΔ Sounds

Itβs 1996 and Jill Clark has been living in Guernsey for less than a year. Itβs been a glorious summer and she is looking forward to her 25th birthday. Like for most young people looks are important to her. A journey home from the pub is about to make Jill question the importance of the human face.

More to discover on Radio 4

-

![]()

Life Changing with Jane Garvey

Jane Garvey talks to ordinary people about an extraordinary turning point in their life.

-

![]()

Fortunately... with Fi and Jane

A highly contestable list of nine great Fortunately⦠moments

-

![]()

The Flipside with Paris Lees

This science and storytelling podcast tells two stories that feel opposing. As the stories unfold, we'll come to reflect on why we behave the way we do.

-

![]()

The Anatomy of Kindness

Using evidence from the ΒιΆΉΤΌΕΔ Kindness Test, neuroscientists and evolutionary psychologists, broadcaster, author and psychologist Claudia Hammond interrogates what it means to be kind.