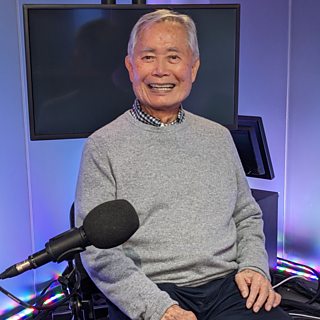

George Takei: Seven things we learned from Historyβs Secret Heroes

In the ΒιΆΉΤΌΕΔ Radio 4 podcast History’s Secret Heroes, Helena Bonham Carter shines a light on the extraordinary stories of some of the most fascinating unsung heroes from the Second World War.

In one episode George Takei speaks about the American Internment Camps. He is known to millions as Sulu from the original Star Trek series. As a child growing up in the United States during World War II, though, he and his family were caught up in the persecution of Japanese-Americans as suspected enemy sympathisers after the Japanese attack on the American base at Pearl Harbor. In 1942, aged just five years old, Takei was interned by the United States Government in a series of camps. More than 125,000 Japanese-Americans were forcibly relocated and interned during the war, solely because of their ethnic background.

In later life, Takei has become a powerful spokesman, raising awareness about the internment of Japanese-Americans and the trauma and destitution they suffered as a result. Here are seven things we learned from his story…

1. Takei and his family were first interned in stables built for horses

After President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 in February 1942, thousands of Japanese-Americans were arrested. George Takei’s family were apprehended at their Los Angeles home by two soldiers with bayonets. While internment camps were made ready for them, they were taken to the Santa Anita Park racecourse on the outskirts of Los Angeles. Takei remembers: “We were unloaded, herded over to the stable area, and each family was assigned a horse stall to sleep in.” They stayed there for four months.

We were unloaded... and each family was assigned a horse stall to sleep in.George Takei

2. Takei’s parents pretended that this was all an adventure

The Takeis were among many internees moved by train from Los Angeles to Camp Rohwer in Arkansas. So as not to scare their sons George and Henry, they told them that they were going on holiday. “Henry and I were jumping for joy,” Takei remembers. But they were surprised to see adults in the train carriage crying.

3. Conditions at the internment camps were harsh

Many rooms in Camp Rohwer had no beds and the plumbing was unfinished. There were swarms of mosquitoes, and the camp was surrounded by barbed wire and sentry towers.

George Takei recalls his childhood in an internment camp in the US

During World War II, over 100,000 people of Japanese descent were incarcerated in the US

4. Japanese-Americans were required to fill out a βloyalty questionnaireβ

In 1943, adult internees had to answer a series of questions. These included a question about whether they would serve in the United States armed forces, and another asking them to swear “unqualified allegiance” to defend the United States from any and all enemy attacks. Takei’s parents were frightened to serve in combat because that would mean leaving their young children behind. They answered no to both questions. As a result, they were designated disloyal, and the family was moved to the maximum security Camp Tulelake in northern California. This camp was overcrowded and was guarded by tanks and 1000 military policemen. After thousands of internees protested, conditions became even harsher, including solitary confinement, beatings and torture for those who resisted.

5. Many Japanese-Americans who did fight for the United States distinguished themselves in service

Japanese-American men who answered “yes” to the loyalty questions were drafted into the 100th and 442nd Infantry Regiments of the United States Army. The 442nd fought in some of the bloodiest battles in Europe, and became the most decorated regiment in American military history.

6. At the end of the war, internees were released with $25 and a bus ticket

George Takei was nine years old when he and his family were released. He had spent nearly half his young life in internment camps. After their incarceration, the family had lost their business and livelihood, and lived in poverty on Skid Row in Los Angeles. Takei worked hard and later went to college to study architecture, but his real passion was acting. In 1966, he won the role that would make him world famous: Sulu in Star Trek.

7. It took until the 1980s for the United States Government to apologise and make reparations to Japanese-Americans

The generation of adults who had been interned in camps were often reluctant to talk about their experiences, but in the 1960s and 70s the younger generation, led by voices such as George Takei’s, did begin to speak out. In 1980, President Jimmy Carter established a commission. This resulted in the 1988 Civil Liberties Act signed by President Ronald Reagan, which officially apologised to Japanese-Americans for their internment and authorised a $20,000 redress payment to those internees who were still alive. By that time, though, many, including Takei’s father Norman, had died. George Takei remembers: “I told my mother, ‘I wish Daddy were here to see this day.’ And my mother replied, ‘Daddy always knew this day would come.’”

More from the ΒιΆΉΤΌΕΔ

-

![]()

History's Secret Heroes - Virginia Hall's Great Escape

How did Virginia Hall mastermind one of World War Twoβs most astonishing prison breaks?

-

![]()

Inheritance Tracks - George Takei

Mona Lisa by Nat King Cole and Don't Fence Me In by Gene Autry.

-

![]()

Arts and Ideas - Star Trek

Matthew Sweet with George Takei, Naomi Alderman, Una McCormack and JosΓ©-Antonio Orosco.

-

![]()

Woman's Hour - Helena Bonham Carter

The actor on playing Nolly - star of Crossroads and Queen of the Midlands Noele Gordon.