Seven reasons why the yeti might actually exist

The idea of hairy, ape-like creatures roaming around the Himalayas has been around for centuries. But could the yeti actually be real?

In the Βι¶ΉΤΌΕΔ Radio 4 documentary series Yeti, intrepid explorer Andrew Benfield goes on an epic journey through India, Myanmar, Nepal and Bhutan in search of the truth behind these stories.

Together with his more sceptical friend Richard Horsey, they hear surprisingly consistent descriptions of a mysterious, large, hairy creature from local people.

As a new bonus episode reveals the results of a DNA test on a mysterious hair that the pair were given, Andrew writes about the reasons that convinced him and Richard to embark on their globe-trotting adventure…

The yeti – a fantasy creature, the stuff of cartoons, right? That's exactly what my smart, sensible friend Richard thought too. But my travels and conversations in the Himalayas had started to convince me that there was something more to this than just mere myth. So I decided I would try to reach some of the most remote areas of this vast mountain range to get to the bottom of the mystery.

Rational Richard, I reckoned, would be my ideal companion, a resident expedition sceptic who would keep me grounded and make sure I wasn't simply losing my marbles. He was pretty reluctant when I first proposed the idea, so I offered him seven good reasons why he should take the yeti more seriously and come to join me in this quest.

1. Consistent sightings and descriptions

There are consistent stories and descriptions of this creature from across the region, coming from people in some of its most remote areas who have little or no contact with each other or the outside world. These are not just tales of – and sometimes pictures of – strange footprints but rather first-person sightings and even reports of physical attacks on livestock and people.

While some of these accounts might be explained away by misidentifying a bear on its hind legs or an over-active imagination, others involve multiple witnesses, physical evidence, and even police reports, so are not so easily dismissed. In many parts of the Himalayas, the yeti’s existence is an accepted fact and one country, Bhutan, has even created a national park specifically to protect its natural habitat.

2. David Attenborough thinks the yeti could exist

Some quite smart people think it may exist, including Sir David Attenborough, Tenzing Norgay (the first person to summit Mount Everest along with Sir Edmund Hillary) and even Alexander the Great.

Sir David was asked in a 2013 interview if he thought there were still any big creatures left out there for science to discover. He responded by immediately suggesting the yeti. That was what really convinced me there was something to this and that I wasn't just chasing after unicorns.

3. The western perception of the yeti is all wrong

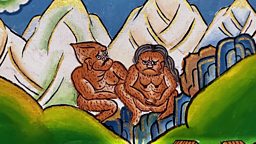

But none of these people are talking about the big white fluffy snow monster from the cartoons and B-movies – that image, as well as the name 'abominable snowman', are western inventions from the 1950s, used to fetishize and sensationalise the yeti in order to sell newspapers and films.

We know there used to be a giant ape roaming around the Himalayas, because we have the fossil evidence to prove it.

That's helped ensure it's been consigned firmly to the fantasy realm for people outside of the mountains. What local people instead describe is a brown-haired bipedal (walking on two legs) mammal that looks something like a giant orangutang or a gorilla.

4. There's actual evidence of an ancient giant Himalayan ape

And, here's the kicker, we know that there did used to be a giant ape roaming around the Himalayas – because we have the fossil evidence to prove it. It was 9ft tall and called Gigantopithecus.

Its closest known living relative is the orangutan, but Sir David Attenborough believes that descendants of Gigantopithecus might still be surviving in the remotest parts of these mountains (and we really shouldn't argue with a British national treasure).

5. New species are always being discovered

Scientists are still regularly discovering new species out in the most remote areas of the globe, including some large mammals, such as antelope and deer. And, remember, Westerners previously dismissed stories about the panda, the hippo, the giraffe, and the gorilla as fantastical inventions, just local folklore and fairy tales.

In fact, there has been a longstanding historical bias in the West against believing such accounts, a refusal to accept that people in these remote areas could possibly know something that outsiders don't already. Which is rather ironic when it's those local people's expertise in their own flora, fauna, terrain and climate that keeps the outsiders alive and well when they're paying a visit.

6. There are huge areas of the Himalayas that are still largely unexplored

We are talking about immense, unexplored areas here, and some of the most inhospitable habitats for humans on earth. Until you've walked for days in the Himalayas, it's hard to appreciate just how vast and inaccessible so many of these mountains and valleys really are, and how rarely, if ever, the majority see any human activity. So there's a genuine topographical possibility for a creature to exist largely unseen.

Until you've walked for days in the Himalayas, it's hard to appreciate just how vast and inaccessible these mountains and valleys really are.

7. We're taking a different approach

Of course, Richard and I wouldn't be the first foreigners to go to the Himalayas looking for the yeti. But nearly everyone before us had taken what, I felt, was a rather arrogant approach, thinking they could spot something in a few weeks that locals are lucky to see once in a lifetime. What I proposed to Richard was a different tack. Rather than trying to see one ourselves, we would focus on tracking down credible local stories.

Taking these more seriously, I believed, was the best way to eventually get our hands on some genuine physical evidence, such as bone or hair samples. Then we could get those samples scientifically tested to prove that it came from a creature that was previously unknown – to the lowlanders, at least.

My arguments somehow persuaded Richard and his PhD to come along, in the role of responsible accompanying adult, although at first I think he was mainly just humouring his eccentric friend. But his scepticism soon began to wane as we ended up finding much, much more than either of us could ever have bargained for.

So why not challenge your own preconceptions and assumptions too, and join us on an epic adventure across Nepal, India, Myanmar and Bhutan? But be prepared to be pushed – as we were – to the absolute limit. The monsters just got real.

To find out how Andrew and Richard's search went, listen to the whole series of Yeti on Βι¶ΉΤΌΕΔ Sounds.

More from Βι¶ΉΤΌΕΔ Radio 4

-

![]()

Uncanny

Danny Robins investigates compelling real-life cases of the paranormal.

-

![]()

Witch

India Rakusen finds out what it means to call yourself a witch today.

-

![]()

Naturebang

Looking to the natural world to answer some of life's big questions.

-

![]()

Has Nessie lost her appeal?

Farming Today asks whether the Loch Ness Monster's popularity is in decline.