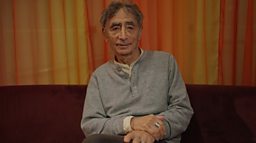

Gabor MatΓ©: Seven things we learned when he spoke to Kirsty Young

In her ΒιΆΉΤΌΕΔ Radio 4 podcast Young Again, journalist and broadcaster Kirsty Young asks fascinating people what advice they would like to give their younger self.

Gabor Maté, is a physician who believes the mind, body and environment are interconnected. Much of his work has focused on the theory that physical and mental illness throughout life can be traced back to trauma suffered in childhood. He argues that medicine focused on treating only the body is failing to treat the source of the problem: the mind. Here are seven things we learned from his conversation with Kirsty.

Young Again: Listen to this episode on ΒιΆΉΤΌΕΔ Sounds

1. He thinks we have to view health differently

Across decades working in medicine, and in his five books, Gabor has laid out the case that you can’t treat a person’s illness if you view it as purely physical. “Everything is connected to everything else,” he says. “You can’t separate individuals from the environment [or] their multi-generational family history, or from the culture they grew up in.”

“You can’t separate the mind from the body, contrary to the way medicine is practiced. Whatever happens to an individual, it’s not just a manifestation of a certain organ. It’s actually the manifestation of an entire life lived in a context affected by multi-generational and cultural factors… it’s all one.”

2. He was given away as a baby

Gabor was born in 1943, in Nazi-occupied Hungary. His Jewish mother, whose parents died in Auschwitz, gave up Gabor when he was an infant. “I’m 11 months of age and, to save my life – literally to save my life – she hands me to a total stranger, Christian woman in the streets, and says, ‘Please take this baby… to some relatives who are in hiding, because I can’t keep him alive.’”

Donβt beat yourself up. You were doing your best according to the lights that were guiding you at that time.βGabor on managing regret and self-criticism

He says that trauma, felt at such a young age, is remembered by the body. “I [as a baby] experience that the world is a dangerous place. That’s downloaded into my nervous system… So I grow up with that unconscious sense of fear of abandonment and having to prove the value of my existence. I can’t be valuable on my own, otherwise [my mother] wouldn’t have given me away.”

3. He doesn’t believe in blame

Asked what his mother could have done differently, Gabor says, “She could not have done anything other than this.” He chooses not to blame people for unintentionally causing trauma. “Parents are, for the most part, trying to do their best,” he says. “And if they don’t do their best, or even if they hurt their kids, that’s only because they have unresolved trauma from their own childhoods.”

He acknowledges he negatively affected his own children, when he understood himself less well. “I passed on certain aspects of my trauma to my children,” he says. “I didn’t mean to. I did my best. I loved them, but I didn’t know what I didn’t know.” He threw himself into long hours as a doctor, in order to feel important and needed, to the detriment of his kids. “If you have the sense you’re not wanted, the best advice I can give you is: Go to medical school. They’ll want you all the time… The impact [of that] on my kids is dad is never around.”

4. In his 50s, he realised he was a workaholic

Gabor spent 12 years in Vancouver working with people addicted to drugs. In their behaviour, he saw similarities with his own. “As I looked at their addictions, I began to recognise that… those addictive tendencies are very much present in me,” he says. “Not acted out in the same extreme way as theirs. Quantitatively, a big difference, but qualitatively, I saw myself in them. I realised how addicted I was to work.” He was in his 50s at this point.

He describes addiction as “any behaviour in which a person finds temporary relief or pleasure, so therefore craves, but then suffers negative consequences as a result, but doesn’t give it up. It’s not about the substance: it’s about craving.” He believes all addiction should be treated seriously, citing his own shopping addiction. “People say, ‘How can you compare your [shopping] addiction to heroin addiction?’ Well, the differences are obvious. It’s the similarities that interest me.”

βAddiction is a response to emotional painβ

Addiction specialist Gabor Mate says dealing with past trauma is key to breaking addiction

5. He wants to engage with those who disagree with him

Gabor’s views are not universally accepted. Asked what he’d say to those who think he’s wrong, he says, “Look at the evidence. Don’t believe me just because I’m saying it. In all my books I cite all the scientific sources... For [my most recent book] The Myth Of Normal, I collected 20,000 articles… Look at the evidence and tell me where I’m wrong, but don’t tell me I’m wrong until you’ve looked at the evidence.”

6. He thinks we use ‘normal’ incorrectly

“The word ‘normal’ is a useful word as long as we use it in the proper context,” says Gabor. “In the physiological sense, a certain range of blood pressure is healthy and natural… What’s healthy and natural is then synonymous with ‘normal’. We make a huge mistake when we transpose what’s ‘normal’ to social conditions and think that what we’re used to is normal.”

“In so many aspects of this society, this culture and our way of life, what is normal, in the sense that we’re used to it, is neither healthy nor natural. In fact, it makes us sick. That’s why the book is called The Myth Of Normal.”

7. He doesn’t carry regret

Gabor says he has managed to let go of regret and self-criticism. Asked how, he says, “It’s very gradual. It’s a matter of self-forgiveness, in a certain sense. Self-compassion, actually, and saying to myself, ‘Look, don’t beat yourself up. You were doing your best according to the lights that were guiding you at that time.’ Also, in watching my kids do their own healing and getting on with their own lives, and seeing that I didn’t totally screw them up.”