Six remarkable objects to take you around the world

In A History of The World in 100 Objects the former Director of the British Museum Neil MacGregor takes this listener on a trip around the world and back in time. In each of the episodes in the series he tells the fascinating stories behind a chosen item, which may be anything from a mundane tool to a great work of art, but which must be man-made. The series is chronological, beginning with some of the earliest objects from Tanzania dating back almost two million years, and running up to the present day.

Here we shine a light on just six of the fascinating objects discussed in the series. Read on to be transported back over two thousand years to learn more about the worlds from which they came. We'll navigate Ancient Egypt and the Roman Empire, glimpse the treasures of Turkey, pay our respects to a Mayan god, and marvel at a Hawaiian helmet.

-

![]()

Listen to A History of The World in 100 Objects

Neil MacGregor retells humanity's history through the objects we have made.

Coin of Croesus (~550BC)

If you have a lot of personal wealth, you might be said to be as “rich as Croesus”. But just who was he? More than 2500 years ago, King Croesus ruled in Lydia, a prosperous kingdom in western Turkey, from where some of the world’s first coins entered circulation.

While coins made of electrum (a mix of gold and silver) date back around a century before the reign of Croesus, it is thought that the Lydians were the first people to make use of a bimetallic currency, using gold and silver separately in coins.

If you have a lot of personal wealth, you might be said to be as βrich as Croesusβ. But just who was he?

The river from where the Lydians sourced the metal for their coins is also supposedly the river in which King Midas washed away his ability to turn all he touched into gold. The lion, a symbol of royalty, and the bull would have been punched into this beautiful bright coin with a hammer.

Listen to A History of The World in 100 Objects to find out more about the coin of Croesus.

Chinese Bronze Bell (~500BC)

This intricately-decorated bronze bell is known as a bo, and it’s a pretty sophisticated instrument – bells of this size didn’t appear in Western music for another millennium! Its handle is shaped like two dragons, and the instrument’s body is adorned with dragons swallowing geese.

The two notes produced by this bo would have been heard in China some two and a half thousand years ago, and its music may even have been heard by contemporaries of Chinese political philosopher Confucius. The China of this time was one defined by unrest and political fragmentation, but among this turmoil Confucius’s message was one of peace and harmony, to be achieved by returning to traditional values of virtue.

Not just a renowned philosopher, Confucius was also a musician, and he felt strongly that the performance of music could bring about the harmony he wanted to see in society.

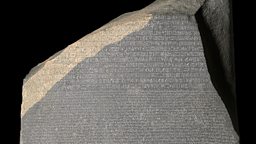

The Rosetta Stone (196BC)

While this hefty lump of grey rock may not be much to look at, the Rosetta Stone is undoubtedly one of the most renowned objects in the British Museum.

It is inscribed with a decree to mark the 13-year-old King Ptolemy V’s status as a god on the first anniversary of his coronation in 196 BC. Being so young, Ptolemy was at the mercy of his priests who he appeased with some very lucrative benefits, also immortalised on the stone. Effectively, it laid out their tax exemptions. While it’s hardly a gripping read, the fact that the text was transcribed in three languages – Greek, hieroglyphs and demotic Egyptian (the everyday language) – is hugely significant. Greek was the official language of state administration, and remained so for a millennium.

Within five hundred years, the priestly language of hieroglyphics had fallen out of use, and this ancient Egyptian language became incomprehensible. The presence of Greek, which scholars could read, opened up the hieroglyphs to interpretation, when it was excavated during Napoleon’s campaign in Egypt. When French scholar Jean-Francois Champollion realised that all the hieroglyphs were both pictorial and phonetic (working as both images and sounds), he eventually cracked the Rosetta stone, making the language of Ancient Egypt accessible for the first time.

Maya Maize God Statue (~700AD)

As civilisations became dependent on agriculture, some 9000 years ago, stories of new gods emerged: gods who guaranteed the cycle of the seasons and the crops’ return, and gods of food itself.

This particular statue is a god of maize – a staple crop of the Americas that flourished when meat was scarce. Maize was thought to have sacred properties, as it was believed the Mayan’s ancestors were crafted from corn dough by the gods. This adaptable and readily available crop was nonetheless quite stodgy, and Mexican farmers quickly learned to cultivate flavoursome chillies to add some pizzazz to the dull carbs. It is still a staple cuisine today.

This handsome limestone statue is thought to be 1300 years old. It now resides in the heart of the British Museum, but was found in the ruins of a pyramid-like temple in Copan, a major Mayan city in modern-day Honduras. The bust is adorned with a headdress shaped like an ear of corn. Its over-sized head may not even belong to the body on which it sits, as statues at the temple fell and were pieced together again.

Hoxne Pepper Pot (400AD)

This beautiful, if somewhat startled-looking, silver woman is, in fact, a pepper pot – you can tell this by the holes in its bottom. Described by Neil MacGregor as ‘a bit of kitsch for the rich’, the figure itself may have been based on a wealthy late-Roman aristocrat – the sort of woman who would herself use such a pepper pot.

Excavated from a site in Suffolk as part of the Hoxne hoard, this ornate utensil represents a melting pot of cultures. Her owners lived at the tail-end of Roman rule in Britain, by which point the Romans had intermingled with, and even married, the native people. Locals tried their best to act like Romans, from their fashion choices to the food they ate.

Romans were serious foodies, and the key spice in their armoury was pepper.

Romans were serious foodies, and the key spice in their armoury was pepper. But this sought-after seasoning didn’t grow in England, or even Europe. Instead, the Romans imported it from India. A shipload of pepper is estimated to be worth seven million sestertius. At a time when a Roman soldier earned around 800 sestertius a year, a potful of this seasoning didn’t come cheap.

Hawaiian Feather Helmet (1778)

This striking red and yellow helmet was presented to Captain Cook, or one of his crew, in 1778 when he and his men became the first Europeans to visit Hawaii.

Adorned with the vibrant feathers of thousands of honeyeater and honeycreeper birds, this helmet would probably have been sported by the highest-ranking Hawaiian chief to communicate with the gods.

Birds were seen as spiritual messengers, and their feathers were thought to bring protection and power, so the bestowal of this helmet would have been a great honour. Cook spent a happy period on the island repairing his ship and mapping the island, but within a month of embarking on his journey north, a storm forced him to return. This time, the locals were less welcoming, as they had entered into the season dedicated to the god of war. One of Cook’s boats was stolen and in an attempt to negotiate its return he planned to hold one of the chiefs hostage, but a melee broke out and Cook was killed.

A History of the World in 5 Minutes

A History of the World in 5 Minutes

2 million years, 100 objects, 5 minutes.

More from Radio 4

-

![]()

Download: A History of the World in 100 Objects

Neil MacGregor narrates 100 programmes that retell humanity's history through the objects we have made.

-

![]()

Introducing You're Dead To Me - Series 2

Greg Jenner introduces the new series of his ΒιΆΉΤΌΕΔ history podcast, You're Dead To Me.

-

![]()

Listen to In Our Time

Melvyn Bragg and guests discuss the history of ideas.

-

![]()

Welcome to ΒιΆΉΤΌΕΔschool History

Something for the whole family: a fun 15-minute history lesson with Greg Jenner.