Not Your Usual Ghost Stories

Somewhere off the beaten track between the town of Thirsk and the city of York lie the ruins of Byland Abbey, just one of a cluster of remarkable Christian monasteries established in the 12th century in the wilderness of North Yorkshire.

Little remains of that bustling Abbey today: there is a strong footprint in the Yorkshire soil, and some of the locally mined limestone arches and walls stand defiant, giving a hint of the original shape, but the roofs have been stripped and the monastery lies corroded and open to the elements.

Remarkably, some manuscripts from the Abbey library survived its destruction; Radio 4’s Sunday Worship gave an account of the famous "Byland ghost stories" – startling medieval tales, through which we can catch a glimpse of thoughts on death and dying in those distant times.

Here’s what we learned.

Byland Abbey, North Yorkshire. Photo © Getty Images

The ghosts in the Byland manuscript...

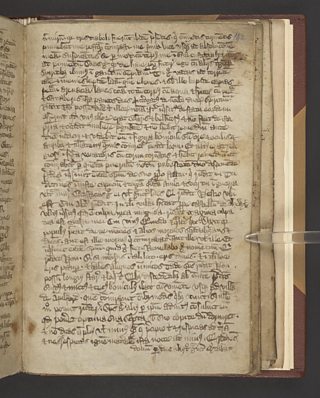

Dr Eleanor Jackson, Curator of the illuminated manuscripts at the British Library, introduces the Byland manuscript: "At the top of the first page we've got the ownership inscription of Byland Abbey. It's quite typical of a monastic library book from this period. It's quite functional, written in a small neat script. There's not very much decoration, although there is a rather lovely red decorated letter to begin the text. You can see that it's been really well used over its lifetime. Lots of monks have studied this text, with lots of little annotations and notes in the edges of the pages.

What's striking about the Byland Abbey ghost stories is this idea about how the living have a duty of spiritual care towards the dead.Dr Eleanor Jackson, British Library

"One of the things that's really striking about the Byland Abbey ghost stories is this idea about how the living have a duty of spiritual care towards the dead? Most of stories are about people who've died with sins that they haven't rectified. They come back and they want to get living people to help them put these sins right, so they can get into heaven.

"This was part of a much wider medieval culture of taking care of the souls, praying for the dead; this was something that the monks of Byland were obviously engaged in, but it was also something that was especially important to medieval women's communities because women were not allowed to join the priesthood. They were not able to perform spiritual care through performing priestly functions; so the main way in which they were able to provide spiritual care was by praying for the souls of the dead – you have a lot of this kind of medieval death culture coming from nunneries as well."

Why monastic ghosts appear on Earth

"There's a very touching German ghost story written by a Cistercian monk called Caesarius of Heisterbach," adds Michael Carter, Senior Properties Historian at English Heritage. "It involves a young nun called Gertrude in a German Cistercian monastery. This is a reminder that women were an essential component of the Cistercian life. In fact, in Yorkshire where there were eight male Cistercian abbeys, there were 12 cistercian nunneries and their prayers were esteemed by people in the locality.

"Sister Gertrude dies and a few days after her death, her spirit appears in the choir stalls, a bright apparition around the hour of Vespers, one of the great services; her sister in the religious life sees this apparition and is much troubled by it. It's also seen by the Mother Abbess who provides instruction saying, 'Should it appear again, say to it blessings. And if it replies of the Lord, you can know it has been sent from Christ, and not from Satan.' The apparition appears again; the nun asks the blessings and gets the appropriate reply. And the Sister Gertrude spirit says, 'I've come back from purgatory because I used to whisper to you in the choir when I should have been singing the Divine Office; I come back as a punishment and also as a warning to you to give up girlish things and to embrace your life as a religious person.' Gertrude has to do this on three occasions before she is released from her purgatorial pains.

"This touching story is a reminder of mortality in the Middle Ages but also of the bonds that endured in the cloister beyond death: that it is your spiritual responsibility to pray for your brothers and sisters and religious life, indeed, all Christian souls. But it's also a reminder of just how hard life as a monk or nun was. Even what to us was very minor transgression – whispering to your friends – can earn you a place in purgatory where torment will be inflicted on your soul until it has been purged of sin and you can find peace in heaven."

-

![]()

Saints, Souls and Spirtis

Father Dermot Preston presents from the ruins of Byland Abbey. The service is all about Saints, Souls & Spirits; Byland is a rich source of reflection on all three, close to the "triduum" of Halloween/All Saints/All Souls which opened the month of November, the traditional time when Christians remember, and pray for, the dead.

A rotten revenant

"One of the ghost stories that is actually set here within Byland Abbey doesn't involve a soul searching the prayers of the monks seeking spiritual salvation," says Michael Carter. "It involves a revenant. His name in life was James Tankerley; he was a local parish priest and was buried before the entrance to the chapter house at Byland – that's one of the very best places in a monastery to be buried of all. And he rose, the story says, at night from his grave and wandered over the Moors to nearby Cold Kirby where he'd been parish priest, and gouges out the eye of his former concubine. The story continues that the monks were somewhat perturbed by these happenings; the community resolved to exhume the body of Tankerly and to throw it in a nearby lake.

"This is because these 'revenants', which have their origins in the dark imaginings of the forests and meres of pre-Christian Northern Europe, cannot be saved by pious prayer – they are evil to their rotten core. Tankerley's body was placed on a cart and taken to a nearby lake, the Goremire, which the Abbey owned; we are told that the oxen dragging it almost baulked in fear. But the author of the ghost stories added a note at the end and said, well, what if indeed Tankerley's soul could have been saved? What have my brethren here done? If he could indeed one day have been counted amongst the blessed? There's a real reminder there, that it's the business of monks to be saving souls, not damning them to perdition."

-

![]()

A related exhibition, Medieval Women: In Their Own Words, runs at the British Library until 2 March 2025. The exhibition tells the history of medieval women through over 140 items, including original documents and artefacts, some never seen before in the UK, that explore the experiences of women in Europe from 1100-1500 from across cultures, religions and class. [External site]

-

![]()

Sunday Worship

Radio 4's Sunday morning service.

-

![]()

Prayer for the Day

Radio 4's daily prayer and reflection.

-

![]()

The Daily Service

A space for spiritual reflection with a Bible reading, prayer and a range of Christian music.

-

![]()

Beyond Belief

Radio 4's series explores the place and nature of faith in today's world.