A little bird blown off course...

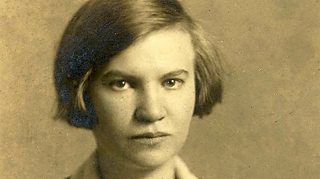

The extraordinary story of a remarkable photographer and musical folklorist is told in Radio 3's Sunday Feature: Margaret Fay Shaw's Hebridean Odyssey.

Margaret gave up a privileged upbringing and classical music training in 1920s New York to live in a remote, Gaelic-speaking community in the Outer Hebrides.

Without any knowledge of Gaelic she used her classical training to notate and later record the first proper archive of traditional, unaccompanied song and folklore from the Western Isles.

In 1926 crofters living on the small island of South Uist, in the Outer Hebrides, welcomed a rather strange, exotic visitor.

I wondered what these songs sounded like when they were first heard. The real thing – I would love to hear.Margaret Fay Shaw

She was a young woman who spoke English with a peculiar accent. She wore dark sun glasses. Her clothes and footwear were entirely unsuited to the Hebridean winds and rain and she was on a strange mission - she wanted the islanders to teach her their songs – the Gaelic songs which had been passed down the generations for centuries.

The young woman was an American, Margaret Fay Shaw, and it would be hard to find a greater contrast between her upbringing and life in South Uist in the early 20th century. She was the youngest of five daughters from a wealthy steel making family in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. She was brought up in a grand house with servants – a world of privilege and affluence. She had studied classical music in New York and Paris and had dreams of becoming a professional concert pianist.

But when this ambition was thwarted, because of arthritis in her hands, she turned to another dream – collecting, for the very first time the pure Gaelic folksongs of the Outer Hebrides.

She had first heard and was captivated by the unique melodies when she spent a year boarding at a school in Helensburgh, near Glasgow. Margaret's parents both died when she was a child and Margaret was a restless awkward teenager. Her older sisters and aunts had sent her off in the hope that a year in Scotland, their ancestral home, would help "settle" her.

Margaret and the other pupils were treated to a concert of Gaelic music performed by Marjorie Kennedy Fraser, a singer and musician famed for her arrangements of "Songs from the Hebrides". The young American was thrilled by the songs, but knew she was hearing hybrid English versions – grand sweeping Victorian art forms – not the pure thing.

Eight years later that wish took her thousands of miles to the windswept Hebrides in search of the songs, despite her family's alarm that she was going so far away.

Her passion for the music, her enthusiasm and warmth, her drive to learn everything she could about the islanders' lives made her instantly accepted on South Uist. She lodged with two sisters, Peigi and Mairi MacRae, in their tiny croft in a small glen and learnt how to live the life of a crofter. There was no electricity or running water, no luxuries of any kind. There were cows to milk, peat to cut, small plots to tend. Cooking was over an open fire and clothes were washed in a nearby stream.

"From the moment of my arrival I had to learn how to do without... plumbing was the hardest and I was a poor hand at trimming an oil lamp. I never knew such wind... it whitened the window panes with salt from the Atlantic four miles away. At first the noise of the gales made me as nervous as a cat. But for myself, I never felt better, nor was I ever so happy."

Margaret had found her niche in life. She was to live there for the next six years and develop a lifelong bond of love with Peigi and Mairi and friendship with the crofting families of North Glendale. Music was the backdrop to their life – they sang as they worked, songs of milking and ploughing, of spinning and weaving, songs of love and exile, lullabies and laments.

Gaelic songs are complex sophisticated arrangements, driven by the language. It is an oral tradition and the songs had never been written down before in their pure form.

Margaret's classical training was essential to enable her to notate the songs and she spent hours transcribing, even though, at first, she had very little Gaelic.

“When my new friends realised I wanted to learn their language and save their songs they took endless trouble to help me.”

Paul McCallum, who is a trained opera singer, still lives in North Glendale and remembers his grandmother telling him how Margaret Fay Shaw once got her to sing a song ten times so she could notate it correctly – “to get it just right”.

Margaret was also an early 20th-century pioneer photographer and her pictures of island life on South Uist gained worldwide acclaim when they were printed in magazines such as The Listener and the National Geographic magazine. She recorded some of the earliest cine films. Today, in grainy reels, we see small figures collecting seaweed from the shoreline and carrying it on creels on their backs to spread it on the land, shawled women spinning outside small thatched crofts, children dressed in roughly made Halloween costumes out "guising" – visiting people's houses.

It was through her photography that Margaret was to meet her future husband – Gaelic folklorist - John Lorne Campbell. He visited South Uist in the early 1930s in search of photographs for a book, and they were introduced. They eventually set up home on the small island of Canna, in the Inner Hebrides and spent many years travelling around the islands recording songs, collecting stories, publishing books and promoting a Gaelic way of life. They were later to win international academic recognition for their unique archive which is today still housed on Canna. It's owned by the National Trust for Scotland and is of immense value to scholars, musicians and historians.

Archivist Fiona Mackenzie, herself a professional Gaelic singer, is busy digitising the archive and aims to make it more accessible to a wider audience. She pays this tribute to the unconventional American.

"The work of Margaret Fay Shaw in recording the songs and stories of the people of South Uist in the 1930s is a work of incomparable significance. It took a Gaelic learner to preserve, for the world today, a disappeared way of life. Her work tells us who we are and where we come from.”

Margaret's contribution to Gaelic heritage is marked by an inscription on her gravestone - she chose to be buried on South Uist beside the grave of her beloved Peigi and Mairi MacRae in a headland cemetery overlooking the Atlantic. There's nothing but the ocean between there and where she came from – a poignant resting place for the woman who described her own remarkable life story as "a little bird blown off course".

-

![]()

Margaret Fay Shaw's Hebridean Odyssey

An exploration of the life and work of the remarkable American Gaelic folk song collector.

More to explore with Sunday Feature

-

![]()

Bannockburn Begins

Novelist Louise Welsh explores meanings, ancient and modern, of the battle of Bannockburn.

-

![]()

The Kershaw Tapes - Andy's Kitchen and On the Road in the Americas

Andy Kershaw introduces rare recordings from his personal archive.

-

![]()

Curves and Concrete

How did a maverick Scottish architect revolutionise the design of UK skateparks?

-

![]()

Dissecting Beethoven

Georgia Mann and eminent neurosurgeon Henry Marsh explore the story of Beethoven’s problematic health.