Why it’s OK to be unoriginal

Imitation may be brushed off as the sincerest form of flattery, but being accused of plagiarism can be a galling experience, both for the imitated and the imitator. Matthew Syed found this out first-hand when he discovered that the opening chapters to his book bore a “ridiculous similarity” to a New Statesman feature by writer Ian Leslie.

Though the allegations of plagiarism were disproved, Matthew was left reeling, and in the first episode of Sideways, series two, he finds out whether we’re actually all doomed to unoriginality. Here’s why new ideas are so hard to come by, and what we can do to reignite our originality.

Is it the end of the world?

In the summer of 1998, two films were vying to be the season’s box office hit: Armageddon and Deep Impact. One told the story of the race to save the world from an asteroid on a collision course with Earth, the other the race to prevent humanity’s destruction by a comet. Though there were rumours of plotline theft, nothing was ever proven, so how did two blockbusters with such startlingly similar subject matter come to hit the silver screen within weeks of one another?

As we’re all tapping into the same bank of wisdom, it’s only to be expected that we come up with the roughly the same concepts at the same time.

Film critic Kristen Lopez explains that they were both a reaction to the relative stability of the US at the time. “There was not an emphasis on war, the unemployment level was rather low, so what better way to celebrate that than to show a fictional account of how that could all go wrong?”

But there were other things going on in the world, or rather out of it, that were also influential. Four years previously, the world watched as Jupiter was explosively struck by fragments of a comet. Kristen suggests that, at the time, there was more interest in space exploration than ever before, so it was the ideal setting to show off newly advanced special effects. Rather than one being the product of plagiarism, they were both cultural reflections of a common experience of late-'90s America.

How do “coincidences” come about?

We often emphasise the importance of uniqueness and originality. It’s nice to feel special, after all. How, then, do we keep coming up with the same ideas?

Dr Michael Muthukrishna from the London School of Economics puts it down to our cultural evolution. He explains that our new ideas come when we experience and mull over problems, read articles, have conversations with others and piece all of this together. “The trouble is, the source of those ideas are the source of other people’s ideas too,” he says.

As “cultural animal[s] reliant on socially transmitted information,” humans start to act collectively as a brain, fed, in part, on generations of accumulated knowledge. As we’re all tapping into the same bank of wisdom, it’s only to be expected that we come up with the roughly the same concepts at the same time – known as simultaneous invention. If it’s in our nature, then we’re somewhat doomed to unoriginality.

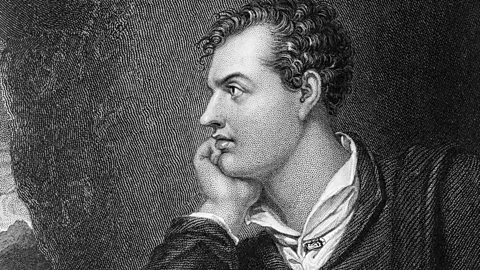

Did the Romantic poets invent originality?

Matthew Syed explores with Professor of English Literature, Nick Groom.

Why does unoriginality feel so bad?

When Matthew discovered that the case studies used in his book overlapped with those in Ian’s article, he says he “felt physically sick”. But if the conception of the same ideas at the same time is part of our human condition, then why do we feel so bad about it?

You should make your range of influences as wide and as original, in a sense, as possible. That’s the one thing you can make original.Ian Leslie

Our hang ups around originality date back to the Romantic period, explains Professor Nick Groom of the University of Macau. Previously, writers “would strive to imitate the ancients, to write in a Βι¶ΉΤΌΕΔric or a Virgilian style. Also to imitate writers such as Shakespeare or Milton,” says Nick. But when the Whig political party grew in prevalence, so too did their values, those of progress and entrepreneurialism. In the mid-18th century, poet and critic Edward Young published his Conjectures on Original Composition which made the case for literature’s commercial value being rooted in originality. “It’s justified in cultural terms,” explains Nick, which “leads to this very marked distinction between what is original and creative, and therefore good, and what is plagiarised and stolen, and therefore bad.” And so began our preoccupation with being original (good and valuable) rather than derivative (bad!).

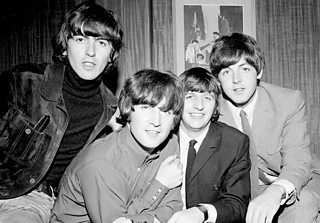

The Rubber Soul Principle

After the incident of his and Matthew’s ideas overlapping, it would be unsurprising if Ian Leslie had some concerns about originality. However, over his career, Ian has rethought what it means to be original, saying that while he may cover topics already explored by others, his unique outlook on them is what makes the ideas feel fresh and unique. He calls this the Rubber Soul Principle, so-called because of The Beatles album of the same name. The Beatles produced Rubber Soul after immersing themselves in Motown music, and while the results had soul influences, the sound was still unmistakably that of The Beatles.

So your thoughts don’t have to be completely ground breaking – in fact they almost certainly won’t be. Yet if two people view the same idea through different lenses, they’ll each have a unique take on it. And those differences will be what add value to their shared idea. As Ian says, “You should make your range of influences as wide and as original, in a sense, as possible. That’s the one thing you can make original. You’re the only person who has this breadth and variety and depth and sophistication of influences.”

To discover more ideas and stories that help us to see the world a little differently, you can listen to Sideways on Βι¶ΉΤΌΕΔ Sounds.

More from Radio 4

-

![]()

Sideways: Originality Armageddon

Matthew Syed asks if we are all doomed to be deeply unoriginal.

-

![]()

What's the secret of making a smash hit pop song?

Exploring the success of Max Martin, the behind-the-scenes genius behind 22 No.1 hits.

-

![]()

Seriously...

Seriously is home to the world’s best audio documentaries. Introduced by Vanessa Kisuule.

-

![]()

You're Dead To Me: Lord Byron

He’s "mad, bad and dangerous to know". He is the scandalous Lord Byron.