Da-da-da-DAH!

Da-da-da DAH! Da-da-da DAH! You might not know a Moog from a mandolin… Da-da-da da, Da-da-da da, Da-da-da dah… or a Korg from an accordion... Da-da-da da, Da-da-da da, Da-da-da dah... but you know this. Da-da-da dah(ah), Da-da-da dah(ah), Da-da-da DA DA DAH!

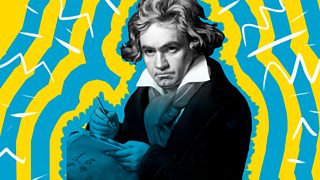

This is the opening of Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony – starting with the most famous four notes in the whole of Western classical music.

What’s stunning about it – what makes it so electrifying – is that there’s no tune as such. It’s all about the rhythm, this obsessive four-note dynamo that propels through the Fifth Symphony’s first movement.

Here's our quick guide to understanding the music, how musicians down the ages from classical to pop and disco-funk have been inspired to adapt and re-version it, and what you can get away with...

Starter's orders

Take a look at how Beethoven started his previous four symphonies:

- No. 1 – Slow violin tune (after playing around with a few chords in confusing keys)

- No. 2 – Fairly slow oboe tune

- No. 3 – Cello tune (after two big stabbing chords)

- No. 4 – Slowly shifting – murky, mysterious – tune on strings

But then, with No. 5, we get a smack in the face: Da-da-da DAH!

After Beethoven lands that initial punch he goes on with an all-out assault, hammering out those four notes left, right and centre, with no let-up. In terms of rhythm (that’s the star of this movement – not melody, not harmony) practically the whole of the first 60 bars – in fact most of the movement – is based on this single, tight, four-note cell [From in the Βι¶ΉΤΌΕΔ National Orchestra of Wales recording of the Full Mix].

And when we do get to what resembles a tune (the second subject), starting on violins [], that rhythm jumps immediately back in, swiping away in the background.

In fact, the whole of the first movement is infected with this four-note tick (and it returns in some form or other in each of the other three movements too), creating a momentum that drives right to the end – except for a tiny, freewheeling oboe near the end of the movement that puts the rhythm on ice, temporarily pulling the rhythmic floor from under our feet.

250 years later you might call this Minimalism. Twenty years after that you might call it dance music.

Stem Cells

For Radio 3’s Beethoven Remixed project, the Βι¶ΉΤΌΕΔ National Orchestra of Wales have recorded the individual instrumental parts – the stems – of this movement so that anyone can download and remix them.

There are endless ways to chop up, overlay and uptempo this music.

But it’s these four notes that are the real stem, the killer kick, hook or break – the Alpha and Omega, the morning, noon and night of this movement.

Would Beethoven have approved of his masterwork being cut up and remixed?

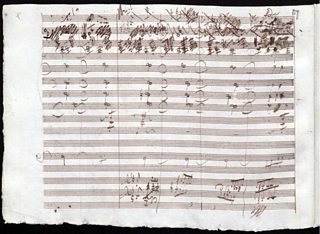

Probably not, especially when you consider he sweated over the manuscript score, which you can see is littered with crossings-out, rejections and rewrites. But he did believe in the universal message of his music, and he would surely have liked the democratic nature of this project – putting music in the hands of the people.

It's all good

In any case, "traditional" orchestral performances of Beethoven’s Fifth – or any of Beethoven’s nine symphonies for that matter – can already be so contrasting (in speed, phrasing, number of musicians) that you’re practically not hearing the same piece anyway. Exploring the following YouTube links will show that, whether it’s legendary conductor or , whether it’s ("A Fifth of Beethoven"), the or this acoustic mashup of , it’s all Beethoven's 5th, and it’s all good.

That’s the beauty and the strength of this musical icon: it withstands – it even squares up to – a whole panoply of interpretations or treatments, and still comes out fighting.

There are endless ways to chop up, overlay and uptempo this music. What might be less possible is to give it a laidback, chilled-out vibe. Because at some point or other, that compulsive "Da-da-da Dah" will want to kick its way out.

Four notes on those four notes

- Beethoven’s assistant and first biographer, Anton Schindler, claimed that the first four notes represented "Fate knocking at the door".

- During the Second World War the 5th’s opening figure became synonymous with "V for victory" (in Morse code the sound for "V" is short-short-short-long), and was used by the Βι¶ΉΤΌΕΔ as a call sign in radio broadcasts during the Second World War.

- That opening rhythm is more complex than you might think – it actually starts off the main beat rather than on it. So it’s not: Da-da-da Dah! but it’s [*]-da-da-da Dah! where the main (strong) beat is in bold and the asterisk is a rest (or, for the players, a quick "sniff"). That makes it a notoriously difficult piece to start for inexperienced conductors.

- Contrary to Schindler’s claim, Carl Czerny – a pupil and friend of Beethoven – reckoned that the opening pattern came from a songbird – the yellowhammer, which Beethoven heard while out walking in a park.

Beethoven Remixed

-

![]()

Get creative with Beethoven Remixed!

Download the samples of Beethoven's 5th Symphony and upload your creative mixes.

-

![]()

Rachel K Collier's Mix Quick Start Tutorial Part One

The electronic music producer explains how to use software to set up your Beethoven mix.

-

![]()

Beethoven Remixed Privacy Notice

How we collect and use personal data about you in accordance with data protection law.

-

![]()

Beethoven Remixed Challenge – Extra Terms of Use

More important information about your contribution to Beethoven Remixed.