How to stop peaceful protests turning into riots

We’ve seen a definite uptick in civil unrest recently. It started with clashes around lockdown measures in the US and then exploded with the murder of George Floyd, with demonstrations turning to riots and a ripple effect that went global. The economic effects of lockdown have been acknowledged as a potential ‘tinder box’ for potential further unrest.

As part of The Life Scientific series, Jim Al-Khalil speaks to Clifford Stott, Professor of Social Psychology at Keele University and a member of the SAGE sub-group, the Scientific Pandemic Influenza Group on Behaviours (SPI-B), to find out about his work on crowd psychology and on evidence-based policing strategies that dramatically reduced football hooliganism.

From protestor to crowd control expert

As a young person, Stott was often on the other side of the police lines protesting about racism and, later on, the Poll Tax. He considered himself ‘anti-authoritarian’ and it was this sentiment that influenced his study path.

After taking Communication Studies and Psychology A-levels, part-time, Stott went on to study Psychology at the then Plymouth Polytechnic.

“This was my first opportunity to learn about what I was actually interested in,”says Clifford, who had left secondary school with no qualifications.

-

![]()

The Life Scientific: Riot prevention

Professor Clifford Stott tells Jim Al Khalili about his life and work as a crowd psychologist and police advisor.

Are mobs mindless?

Stott’s studies in Plymouth included familiarising himself with the work of academic Steve Reicher (with whom he would later collaborate with for a PhD and co-write a book with) on riots and the idea of the ‘mindless mob’.

When we look at crowds empirically and what people do when they riot, it’s not formless random and chaotic.Professor Clifford Stott

Stott describes that notion as an “outdated perspective on crowds that developed at the end of the nineteenth century.”

“When we look at crowds empirically and what people do when they riot, it’s not formless random and chaotic” Stott says, “it’s structured, normative and captures patterns that reflect ideas and beliefs.”

How is one protest group bringing cities to a halt?

Radical and rapidly-growing environmental protest group Extinction Rebellion.

How demonstrations turn violent: the Poll Tax riot, 1990

The Poll Tax demonstration of 31 March, 1990 was an event that overlapped with Stott’s own political views as well as giving him an opportunity to witness what became a disorderly crowd event and to translate that into scientific research for his PhD.

Stott says that the Poll Tax riot, as it became, is a good example of how a crowd mentality can work in union. In this case, people who saw themselves as peaceful protestors exercising their democratic rights considered mounted police and baton charges as illegitimate use of police force.

At that point the crowd’s psychology changes and, as Stott observes, “they come to see it as justifiable and legitimate to resist the police and to engage in confrontation with them in order to defend themselves and the right to protest.”

The group allegiances of football crowds: the 1990 World Cup

A few months after the Poll Tax riots, Stott found himself in Sardinia for the 1990 World Cup to look at another dynamic of crowd unrest – football hooligans. “As a scientist, I go looking for trouble”, Stott jokes.

Previous research has suggested that a hardcore of fans intent on violence infiltrate crowds and cause trouble. Stott’s research showed that the tactical police response to this would involve treating the whole crowd as one and so “creating a psychological unity between the peaceful majority and violent minority that previously wasn’t there, and that enables an empowerment of those seeking violent confrontation and was escalating it.”

The recommendation of Stott and his team was turn this around by targeting resources.

“You don’t sit with large riot squads outside crowds,” the Professor says, “you put officers in ordinary uniform to work within them, and you build positive relationships with people around you in the crowd so they start to see the police as legitimate.”

The self-regulating hooligan: Euro 2004, Portugal

Stott’s football policing model was given the opportunity for a “massive field experiment” with the 2004 European Championship in Portugal. He adopted a “graded and tactical” approach with the various city police forces there. This meant “putting people on the ground to speak to people, to embed themselves in crowds, to facilitate good behaviour rather than simply focus on the control of negative action.”

Where policing is seen as legitimate, disorder decreases.Professor Clifford Stott

Stott argues that “where policing is seen as legitimate, disorder decreases. Not because you don’t have hooligans present, but because people start to self-regulate. Even the hooligans.”

Ultimately a model adopted by UEFA, it had some interesting results at the time. A case in point was when 500 Croatians walked into Rossio Square in Lisbon where 4,000 England fans were drinking. “These guys had turned up looking for a problem,” says Stott. “A group of self-defined English hooligans came across and started negotiating with the police commander to get rid of the Croatians and stop it kicking off.”

The 2011 London riots

Stott describes the research into the London riots of 2011, sparked by the shooting of Mark Duggan in Tottenham, as a “breakthrough” and a “challenge” for him and his work. Previously, Stott’s research had explained how violence could spread within a crowd but not how riots could spread from one event to another.

-

![]()

The Report: The Riots - How They Began

Wesley Stephenson investigates why the shooting of Mark Duggan in Tottenham sparked unrest.

Though too late to work on the ground – and arguably too risky anyway – Stott and his team mined the wealth of video footage available on social media and YouTube afterwards and triangulated IT with GoogleMaps to build “a really detailed account of how that riot had played itself out.”

The conclusion was that “the psychology though which people in that riot felt united was created through their common experience of stop and search in the months before the riot.”

Stoll believes that, for the first time in the lives of the people involved, they were - in the context of the riot – “more powerful than the police.” This then gave them the “agency” to export the riot.

This put two key factors in sharp relief – first, the breakdown in communication channels between the police and Mark Duggan’s family and the wider community in the crucial 48-hour period between the shooting and the beginning of unrest. Second, is the question of how disadvantaged areas are policed on a day-to-day basis.

Are police attitudes changing?

Professor Stott believes that – despite resistance in some quarters – there is a willingness on the part of some police forces to “adapt and withdraw rather than assert and confront”. This is driven, he believes, by them understanding that crowd action is “driven by meaning” and is not irrational.

Equally, Stott concedes that “there are certain points where heavy use of force is absolutely necessary and absolutely proportionate and appropriate. It’s about how you do that, when you do it and what you do before to avoid having to do that in the first place.”

The politics of science

Over the course of his career Professor Stott says that alongside a duty to provide knowledge and theory, he also has felt “a responsibility to know how to navigate that into the world around me”, even if the scientific community doesn’t recognise this. “In this domain, at least, there is a politic to knowledge,” he maintains.

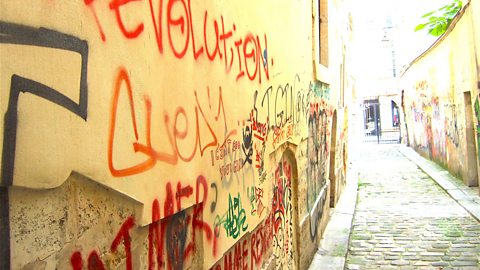

What if the way you express yourself is illegal?

Where should the line be drawn between democracy and vandalism; vandalism and art?

Covid-19 has been a good example of this, with the relationship between SAGE and the government and whether subsequent advice is ‘following the science.’ Stott confesses he is worried about Covid-19 being an “amplifier of inequality” and the various social problems around that, including potential unrest. “It’s really important that we learn from Covid-19 and the relationship between science and politics because the outcome of this is thousands of lives.”

-

![]()

The Reunion: Brixton Riots

Sue MacGregor speaks to five people who were at the centre of events when rioting erupted in Brixton, South London, in April 1981.

Looking back with no anger

“I hope my younger self would aspire to be like I am now,” says Professor Stott. “Many people in the protest community accuse me of collaborating with the police, in a really, really negative way. Most of the cops that I meet on a day-to-day basis - practically all of them, in fact – have come into policing because they want to make the world a better place. What’s the point of turning around and trying to pretend that all these people are bad when they’re not?”

More from Radio 4

-

![]()

The Life Scientific: Riot Prevention

Professor Clifford Stott tells Jim Al Khalili about his life and work as a crowd psychologist and police advisor.

-

![]()

Archive on 4: Riot Remembered

The St Paul's Riot in Bristol in 1980 helped trigger subsequent serious unrest in Brixton and Toxteth.

-

![]()

Seven protests that rocked the world

History has proved that people aren’t always prepared to take things sitting down.

-

![]()

Ten women pushing to make the world a better place

The women pushing to make the world a better place for everyone.