Four reasons Hunger is such a vital book

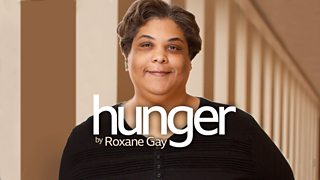

Bestselling American author Roxane Gay does not want anyone to confuse her remarkable book, Hunger, with a weight-loss memoir. She did not write it to offer readers motivation. It is not, she insists, a success story.

Yet readers might beg to differ. Ann Patchett, the Nashville-based writer, says Gay’s memoir “shows us how to be decent to ourselves, and decent to one another,” which should be all the motivation anyone needs to hear Gay’s story.

Here are four lessons from Hunger that show why it is such a vital book…

-

![]()

Listen to Hunger

The intimate, raw and honest memoir.

1. Gay teaches readers the value of being honest

Gay exposes her life with an unflinching honesty that – ultimately – helps to provide salvation, which is all the more remarkable given that Hunger revolves around a shocking incident Gay spent decades trying to suppress.

She writes to share the story of her body – specifically, how her body changed from being that of an average 12-year-old girl to one that, at its heaviest, weighed 577 pounds. She is explicit about the emotional – and physical – pain of living in the world when you are “super morbidly obese”, according to your body mass index.

2. Sometimes it’s okay to acknowledge you are a victim

She wound up as a “woman of size” because she “began eating to change her body” after a boy she loved, plus several of his friends, raped her in a cabin in the woods when she was just 12.

Being raped, she writes, prompted Gay to change her body because she wanted to create a barrier against the rest of the world. “I knew I wouldn’t be able to endure another such violation, and so I ate because I thought that if my body became repulsive, I could keep men away.”

Being raped wasn’t her fault, which is why she finds it helpful to think of herself as a “victim”, rather than a “survivor”, despite surviving what she went through. “I don’t think there’s any shame in saying that when I was raped, I became a victim, and to this day, while I am also many other things, I am still a victim.”

This is important because she doesn’t want to diminish the gravity of what happened, or pretend she is on “some triumphant, uplifting journey”, or that everything is okay. “My body was broken. I was broken.”

3. Often, it’s the rest of the world that’s the problem

Gay was around 420 pounds when she wrote Hunger, making her a “fat woman”, she says. But not an ugly woman. “I don’t hate myself in the way society would have me hate myself. I hate how the world all too often responds to this body.”

I don’t hate myself in the way society would have me hate myself. I hate how the world all too often responds to this body.Roxane Gay

She means the other people on planes; the restaurant designers whose spaces can’t accommodate her body; the retailers who don’t sell clothes in her size; those who erase her gender, calling her “Sir” because she does’t fit narrow ideas about femininity; even the doctors who can’t see past her “morbid obesity” to diagnose a sore throat.

Everyone, in other words, who assumes she is ashamed of herself for being fat, “no matter how close to the truth that might be.”

4. Don’t forget to talk about the unspeakable

Gay didn’t tell her parents what happened in that cabin in the woods when she stopped being a child. She felt she couldn’t. But there were clues. Notably the play she wrote and produced about sexual violence while still at high school. Or when she begged to take a year off before university because she was barely holding her life together. Her parents refused; Gay dropped out.

Incredibly, Roxane's family only found out about her traumatising experience decades later, when disclosures about what happened to her in the woods were published in her essay collection Bad Feminist.

Once Gay saw how understanding her parents were, she says part of her felt “freed”.

Roxane Gay on handling "the after"

Clip from Hunger by Roxane Gay

Gay on writing her story.

More from Radio 4

-

![]()

Hunger by Roxane Gay

Roxane Gay reads the memoir of her body and her hunger.

-

![]()

The Pianist of Yarmouk

Aeham Ahmad’s dramatic story of how he defied the war in Syria with his music.

-

![]()

Ten women pushing to make the world a better place

Ten female freedom fighters to be inspired by.

-

![]()

Eight great life hacks from Caitlin Moran

Flirting, feminism, fashion and how to be a joyous woman.