10 things we learned about words associated with women

In BBC Radio 4's Word of Mouth, author of Mother Tongue: The Surprising History of Women's Words, Dr Jenni Nuttall reveals to Michael Rosen some of the original meanings behind words associated with women.

Going back to Anglo-Saxon and medieval texts, Nuttall has drawn out words that cut right through ideas of highbrow or lowbrow and that have an “everyday register.”

The etymology of many of them is far from straightforward, with a lot of words and phrases having dual meanings and hidden layers, telling a nuanced story of shifting attitudes.

1. The origins of "woman" are a puzzle

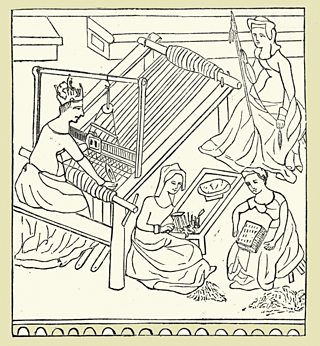

Some Renaissance linguists believed the word woman to be derived from "womb man" (man meaning “human” or “person” in Old English). The word is actually derived from the Old English compound "wyf man", with "wyf" used in Old English for both married and unmarried women. "The origin of the word 'wyf' meanwhile, is much harder to define. It might be something to do with weaving,” says Jenni, “some kind of waving to and fro – I like the idea of the kind of busy woman dashing this way and that way – or it might be something anatomical, swaying hips, but no one's really sure.”

The person looking after a child was not always its mother. 'To mother' in the sense of 'to parent' is much more recent, starting from the mid-19th century.

2. Even Chaucer was squeamish about the c-word

The c-word was used in place names in early Middle English and in medical textbooks. However, attitudes changed in later years, with 18th-century lexicographer Francis Grose famously defining the word as “a nasty name for a nasty thing”. It was around this time that asterisks were being used to disguise the word “if it was printed at all”, Jenni notes. This withdrawal of terminology, in the name of protecting women from rude words about their own bodies, was even seen in the censorship of Chaucer’s texts despite his use of for "queynte", a pun on the c-word, instead of the word itself...

3. Friendlier words for the female anatomy were once available!

Latin terms such as vagina (derived from the word for sheath), vulva and cervix were translated from medieval textbooks and also by physicians popularising the findings of anatomists.

Jenni references some alternative words used by these writers “that offer a kind of synonym” such as port, passage, or womb wicket – “a kind of little gate”.

“They seem friendlier terms than this Latinate language, which is very formal,” says Jenni.

4. Housewife is a multidimensional word

While now restricted to the idea of domesticity and domestic chores, the notion of housewifery once encompassed any kind of economic activity that made a household tick over, such as earning money, managing money, organising supplies and so on.

Medieval mystic Margery Kempe described her plan for one type of housewifery as involving a mill, two horses and an employee. “Housewifery is no small thing in this in this period,” says Jenni, “we've lost sight of the history of that.”

5. Nursing and mothering were not always the same

The origin of the word "nurse" goes all the way back to Proto-Indo-European language. It means “the one who breastfeeds”. From the same origin come words like nurture, nourish and nutrition, which both have a sense of caring but also of rearing and educating.

As Jenni remarks, the related words are “describing the work that’s done, not the person who does it.” The person looking after a child was not always its mother. "To mother" in the sense of "to parent" is much more recent, starting from the mid-19th century.

6. Spinster did not always mean a single woman

The working world was once highly gendered with the use of suffixes to denote who was doing what work, for example "fishwives", "bookwomen", "butterwomen", and "spinster", which meant a spinner of thread or yarn before it came to be used as a legal category for single women.

“You can also see how women are kind of pushed to the edges of the economy,” says Jenni, “they sell the goods that the male guilds aren't so interested in.”

7. Word choices reveal how prevalent working women were in society

Jenni explains that medieval and Early Modern court records reveal that those attending, for example, the scene of a death or an accident included women “doing a much wider range of occupations and work than you would think of from just looking at job titles given to them in official documents”. Women might not be identified by a particular agent noun (such as "digger" or "mower") but they are often recorded as doing the related verb. What’s more, many married women introduced themselves as earning a living “by my labour” or “by my industry” if they appeared in court as witnesses.

8. "Lady" has humble origins

Though it has a low-status origin, meaning "loaf kneader", the word "lady" becomes an honorific title in Old English for, among others, the head of a household, the head of a monastery, or a queen.

“It shows you both women's relegation to certain sorts of domestic work and women wielding power,” Jenni says.

9. Girl was once a unisex term

The word "girl" first appears in the 1300s and is used for both male and female children. By the early 1500s, girl has become specific to females, but it was not age-specific in this context until the 1650s. Before the definition settled, "girls" would often describe women who challenged convention, such as the "Roaring Girls", a title applied to figures such as the thief Moll Cutpurse and Long Meg of Westminster, the alleged owner of a "bawdy house".

"Girl" – from a medieval unisex term to a modern term of empowerment

Dr Jenni Nuttall on the long path to a settled etymology of the word "girl".

10. Rape, rapture and ravishment overlap in their origin

The words rape, rapture and ravishment come from verbs meaning to seize or take away or transport.

“For quite a long time in English,” says Jenni, “rape or ravishment could refer not only to a modern sense of sexual violence, but also mean to kidnap or for certain kinds of property theft, or even for a ward willingly eloping with someone against their guardian’s wishes.”

The convergence of these meanings has often caused confusion for those researching legal history, and Jenni wonders if this “muddying of the linguistic waters” also has a role in what is now called "rape culture" and “the kind of myths and the attitudes that make it much more difficult to prevent male violence and to challenge it.”

-

![]()

Word of Mouth

Radio 4's popular series exploring the world of words and the ways in which we use them, with Michael Rosen.

-

![]()

Women and words: why language matters

Nikki Bedi and Professor Deborah Cameron explore how sexism is reflected in the English language.

-

![]()

Dropping the mic and jumping the shark

Shedding light on the surprising origins of some modern-day phrases,

-

![]()

Are you grammatically gormless or a punctuation perfectionist?

Apostrophes have caused more arguments, disputes and unfettered violence than every family event put together. Test your knowledge with our popular apostrophe quiz!