Bolivia bids to turn coca into compost not cocaine

- Published

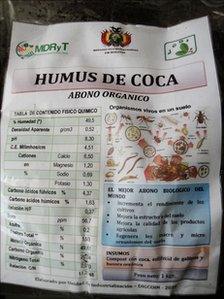

Coca compost: Good for promoting legal crops

Using a small hoe, Miguel Callisaya applies freshly-made coca compost to the top soil of a field in Bolivia's sub-tropical Yungas region.

Emptying the dark brown matter out of small sacks that read "The Best Fertiliser in the World", Mr Callisaya is proud of the results.

He has been leading a project to turn illegal coca crops into organic fertiliser.

And with the trial period deemed successful, coca is set to be used as a stimulant not just for humans, but for plants as well.

By mixing it with other organic matter, such as tree leaves, vegetable scraps and chicken manure, Bolivian officials say some 23 tonnes of coca fertiliser will be produced each month.

Crops do well with the high nutritional value of the new compost.

But for Mr Callisaya, the effect on drug production and trafficking is more significant.

"We are reducing what goes to drug traffickers," he says.

Drug markets

In the surrounding Yungas hills and mountains, coca fields resemble tea plantations, stretching far into the distance. The bright green bushes grow tall under the scorching sun.

Cultivation of coca is protected by the Bolivian constitution but not all the leaves are used for medicinal and traditional purposes.

Miguel Callisaya sees real benefits from using coca compost

According to the , which monitors coca production in Bolivia, some 31,000 hectares (77,000 acres) were cultivated in 2010. Of these, 12,000 were permitted under Bolivian law.

Most of the illegal coca leaves are turned into cocaine that is trafficked to neighbouring Brazil and on to Europe.

The government believes that coca compost will help to deprive drug-traffickers of their raw material, especially when combined with continued reduction of coca fields and dismantling of criminal organisations.

Kathryn Ledebur, of the Andean Information Network, a think tank that analyses drug policy and promotes socio-economic justice in Bolivia, agrees that the initiative should be applauded.

"You achieve two things at once," she says. "You guarantee that the leaf will never be processed into cocaine, an illegal substance, and you provide a rich fertiliser for a nation still dependent on agriculture for subsistence."

Ms Ledebur believes more needs to be done by drug-consuming countries, like Britain, to cut their demand.

But the Bolivian coca compost programme is "a welcome contribution in trying to end the cocaine trade", she says.

However, of the vast quantity of illegal coca grown each year in the country - 36,000 tonnes according to the UN - the Bolivian authorities are only planning to convert confiscated coca into compost.

They have seized some 900 tonnes from the illegal market so far this year, and about 1,000 in 2010 - far short of the UN estimates of illegal coca production.

Alternative crops

Government critics believe that coca compost is being used as a political diversion from really tackling the country's drug's problem head-on.

Only a small fraction of overall illegal production is seized

Opposition politicians think that the fundamental question President Evo Morales should be asking is not what to do with excess coca, but why his administration is failing to significantly reduce the surplus.

In its latest report, the UN calculated that coca production has risen by about 13% since 2006, when Mr Morales - who remains the leader of one of the biggest coca-growing unions in the country - came to power with strong backing from coca farmers.

The UN added that farmers continue to exceed their yearly lawful limit of coca production and that cultivation is expanding into national parks and new areas.

Ms Ledebur said: "It's important to remember that it's poverty, and not criminal intent, that motives farmers to plant coca."

There are projects under way to provide poor farmers with alternative and profitable crops to grow.

But although these are beginning to show results, they need time to take hold.

Bolivia remains under constant international pressure to stop its coca - which accounts for 20% of the world's total crop after Colombia and Peru - ending up with drug traffickers.

Analysts say that coca compost is a small step in the right direction, but is not enough to offer a permanent solution to Bolivia's drug problem.

- Published20 September 2011

- Published18 August 2011

- Published27 July 2011