From hero to zero

- Published

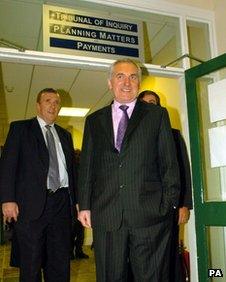

Bertie Ahern after giving evidence to the Mahon Tribunal

The political fall of Bertie Ahern in Ireland has been spectacular.

The former Taoiseach has, in some people's eyes, gone from hero to zero.

The cheers have turned to jeers.

It is only five years ago that he led Fianna Fail to a third successive general election victory and was being tipped as the next Irish president.

Ireland's Celtic Tiger economy was booming, and he was hailed as an international peacemaker after helping to bring political stability to neighbouring Northern Ireland.

He was given the rare honour in the United Kingdom of being asked to address a joint session of the Houses of Westminster, following in the famous footsteps of Nelson Mandela, Bill Clinton and the Dalai Lama.

He also addressed a joint session of the US Houses of Congress.

However, revelations about his personal financial affairs cast a shadow over his latter years in office and led to his resignation in May 2008.

Throughout it all, he robustly defended his integrity, saying he had done nothing wrong and appealing to the Irish people, and fellow politicians, to believe him.

His final words as he stepped down from office were: "I'll submit to the verdict of history."

There is no doubt that history will be kind in terms of his contribution to the peace process in Northern Ireland.

He had an exceptionally good working relationship with his British counterpart, Tony Blair, and together they were key players in securing the Good Friday Agreement in April 1998.

"Tony Blair has been a true friend to me, a true friend of Ireland," he once said.

Only days before the peace deal was signed, Mr Ahern's mother Julia died, but he went straight from her funeral in Dublin back to Belfast for the conclusion of the negotiations.

Bertie Ahern, alongside Tony Blair, at Stormont in 2007 when Ian Paisley and Martin McGuinness were sworn in as first and deputy first ministers

He cut through decades of suspicion and antagonism when he built political bridges with unionist leaders, first David Trimble and then the Rev Ian Paisley.

It was a long process. At the start, Ian Paisley would not even shake his hand.

"But after five years he started to actually explain why he wasn't shaking hands, so I knew I was getting somewhere," said Mr Ahern recently, with a smile.

His sense of humour was often on display, and in private company it was never long before he got talking about the sporting love of his life, Manchester United.

He enjoyed a bit of craic, especially on the campaign trail, and liked nothing better than a pint of Bass with his friends in north Dublin.

A former Taoiseach, the late Charles Haughey, once called him "the most devious, the most cunning of them all".

Mr Ahern laughed off any negative connotations saying it was merely a reference to his proven negotiating skills.

In the early days of his career he was known as an industrial-relations trouble-shooter. In the latter stages, trouble came to his own door.

Ironically, he set up the tribunal which ended up heavily criticising him.

It found that he failed to tell the truth about large sums of cash he had, in different currencies, while finance minister. Bizarrely, he didn't operate a bank account at the time.

Although the report stopped short of accusing Mr Ahern of corruption, it was still damaging.

Looking at the wave of condemnation now aimed at him from all sides of the political spectrum it is hard to believe he was once labelled the "Teflon Taoiseach".

Criticism did not use to stick to him. Not any more.

During the boom times of the Celtic Tiger economy it seemed he could do no wrong. He was lauded at home and abroad.

Fast forward five years, and that economy is in tatters, and so is Bertie Ahern's political career.

- Published22 March 2012

- Published15 March 2012