We've updated our Privacy and Cookies Policy

We've made some important changes to our Privacy and Cookies Policy and we want you to know what this means for you and your data.

Misery in Madagascar after coup

- Author, Linda Pressly

- Role, ΒιΆΉΤΌΕΔ Radio 4, Crossing Continents

You can buy anything on the streets of Madagascar's capital, Antananarivo - second-hand clothes and furniture, cheap toys from China, Malagasy spices, all kinds of food and live poultry.

When President Andry Rajoelina was the city's mayor, he cleared the streets of these informal markets. But now they are back. And everywhere you go in the capital there are stalls.

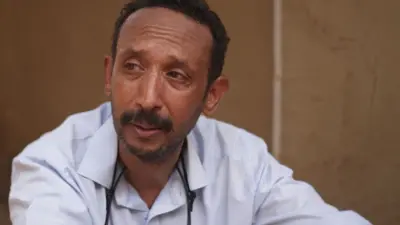

Justin Rakotomakefa is a smallholder, and was hoping to sell a pair of geese.

"There's a lot of competition. Most of the time, I end up taking the geese back home. Since the political crisis, we don't sell much," he says.

In Madagascar everyone talks about "the crisis".

It was in March last year that the 35-year-old Mr Rajoelina became president in a violent change of government.

The international community deemed it a coup, and withdrew all but humanitarian aid.

This has had a dramatic impact on Madagascar because more than half of the government's budget came from foreign donors.

Like many people, Mr Rakotomakefa is struggling to get by.

"It's hard to live. We don't have much money any more in Madagascar. Everybody's trying to sell things on the streets - a lot of the people are from the textile factories."

The textiles industry used to account for 60% of Madagascar's exports, and was worth $600m (Β£387m). But it has suffered massively because of the political crisis.

The African Growth and Opportunity Act enables African governments to access the US market without paying duty if they show a commitment to democracy.

Economic shutdown

But the Obama administration suspended the agreement with Madagascar because President Rajoelina failed to reach an agreement with the opposition, and hold elections last year.

As a result, factories that made clothes for the US have stopped working. Fifty thousand people have lost their jobs.

Odette Razafindratsara's husband was one of them. The couple live in one room with five children.

When the political crisis began to affect the Malagasy economy last year, Mrs Razafindratsara's sister went to Lebanon to work as a domestic servant. She left her two children with Mrs Razafindratsara.

The family survive on the little money Mrs Razafindratsara can earn from taking in washing. The children have stopped going to school because she cannot afford to send them.

"Many families are having problems keeping children in school," says Bruno Maes, the Unicef representative in Madagascar.

"And there are daily difficulties finding enough food. But the biggest challenge for children in Madagascar is access to healthcare. A quarter of health centres have closed, and the whole system of the purchasing and distribution of essential drugs is currently collapsing across the country."

More than half of Madagascar's children are malnourished. The country has 45 centres to treat children with severe acute malnutrition. They used to provide a free service, but they were forced to start charging.

At one point last month, the centre attached to the Befelatanana Hospital had only one patient because parents could not afford to pay for medicines, and the unit had no milk supplies left.

Donne was that one patient. He is three, and is suffering from the effects of tuberculosis as well as malnutrition. His grandmother Fosatry was with him night and day on the ward.

"Now he is feeling better, but the only problem is his chest. When we left our place, his eyes were always closed. Now he can sit up and open his eyes sometimes."

Fosatry paid $50 for Donne's treatment - the equivalent of a low monthly wage in a factory in Madagascar.

"It is very expensive, but it is for medicine for my grandson, so we have to do what we can to come up with the money."

Since the end of June, Unicef has resumed funding all the centres for children with severe acute malnutrition in Madagascar, so the beds in the ward at Befelatanana Hospital have started to fill up once more.

Madagascar is a poor country, and it is getting poorer. Until there is a political solution - a settlement involving opposition groups, and a timetable for elections - it is unlikely the international donors will return.

Top Stories

More to explore

Most read

Content is not available