WWII veteran loses ruling on expats voting in UK elections

- Published

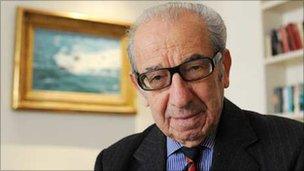

Harry Shindler says his campaign has cross-party support

A 91-year old British man who has fought a campaign for long-term expats to be able to vote in British general elections has lost a ruling at the European Court of Human Rights.

Harry Shindler says the current voting ban on anyone living abroad for more than 15 years infringes his rights.

Despite living in Italy since 1982, he insists he has strong ties with the UK.

The Court said the UK should have "room for manoeuvre" over eligibility for voting and its laws were proportionate.

The World War II veteran, who retired to Italy in 1982 and has not been able to vote in a British general election since 1997, has the right to appeal against the verdict.

He has suggested he will continue his fight by taking the matter to the United Nations.

Mr Shindler first took the case to the ECHR in 2009, arguing that rules excluding British citizens living abroad for more than 15 years from taking part in general elections effectively disenfranchised him and up to a million other Brits.

He has argued that no time limit should be imposed on the right of British citizens resident abroad to vote in their country of origin while they remain a citizen.

'Significant burden'

He has pointed to the fact that he has family members in the UK and a British bank account and is in receipt of a state pension as proof of his close links to the country.

In its judgement, the Court determined that the UK was entitled to confine the vote to those citizens with a "close connection" to the UK and those "who would be most directly affected by its laws".

Given that Mr Shindler would be able to vote if he returned to live in the UK, it ruled that the current laws did not infringe the "very essence" of his rights to take part in free elections.

It noted that different countries had different rules about eligibility for elections and it was important that they should be given leeway to do so as long as they "struck a fair balance".

The seven judges agreed that the 15-year threshold was "not an unsubstantial period of time" and that the UK Parliament had considered the matter in some detail.

They wrote: "Having regard to the significant burden which would be imposed if the UK were required to ascertain in every application to vote by a non-resident whether the individual had a sufficiently close connection to the country, the Court was satisfied that the general measure in this case promoted legal certainty and avoided problems of arbitrariness."

The "restriction imposed on Mr Shindler's right to vote was proportionate to the legitimate aim pursued", they added.

The UK government has said a person's connection with the UK is likely to diminish if they are living permanently abroad but they are prepared to re-examine the 15-year threshold.

It is estimated that 5.5 million UK citizens live abroad, but fewer than 13,000 had registered on UK electoral rolls by 2008.

- Published10 May 2012

- Published17 May 2011