Gerry Adams' imprisonment legally flawed, court hears

- Published

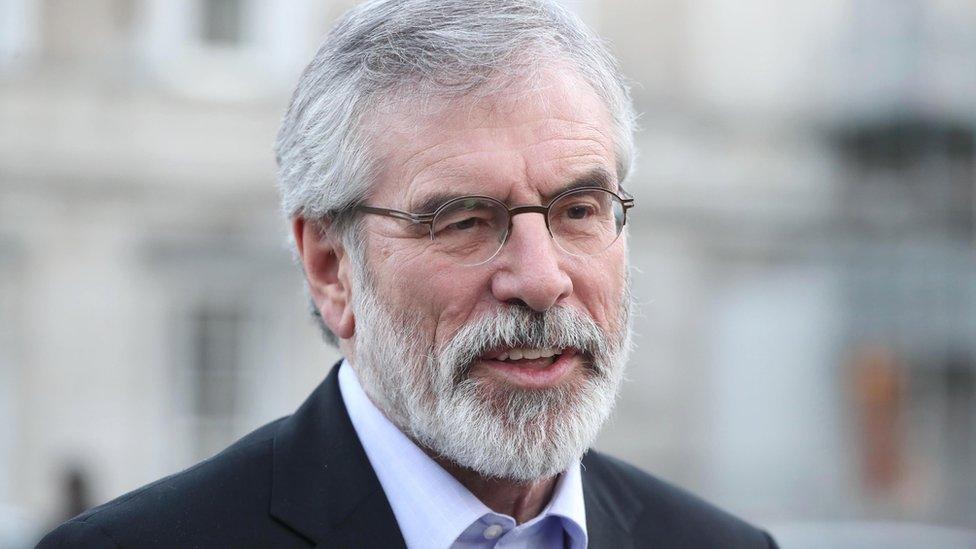

The Louth TD is due to step down as his party's president next month

Sinn Féin's Gerry Adams was unlawfully imprisoned in the 1970s because an order for his internment was legally flawed, the Court of Appeal has heard.

Mr Adams' lawyers argued at the Belfast court for two convictions he received for attempts to escape from prison in Northern Ireland to be quashed.

The Louth TD is due to step down as his party's president next month.

He was among hundreds of people held without trial during the early years of Northern Ireland's Troubles.

Mr Adams was not present as three senior judges heard details of both attempts to flee from the Long Kesh detention camp, the site of the Maze Prison.

On Christmas Eve 1973, he was among four detainees stopped by wardens while allegedly trying to cut their way through the perimeter fencing.

He tried to escape again in July 1974 by switching with a kidnapped visitor who bore a "striking resemblance" to Mr Adams, the court heard.

That man had been taken from a west Belfast bus stop, had his hair dyed and was given a false beard before being driven to the prison for the "elaborate scheme".

But Mr Adams was arrested after being spotted by staff in the car park and he was sentenced to 18 months in jail for attempting to escape.

'No consideration given'

The Sinn Féin leader's bid to overturn his convictions centres on the recovery of a document from the National Archives in London.

His legal team argued that the Northern Ireland Secretary had to authorise interim custody orders used to intern suspects.

Parliament had ensured it could only be exercised at such a senior level because it was such a draconian power, they said.

The court was told that a junior minister in the government's Northern Ireland Office signed the order for Mr Adams internment in July 1973.

Mr Adams' barrister told the court that evidence showed there was no consideration given by the secretary of state.

He said there was a "clear distinction" in the legislation's wording about who had the power to make an order and who had the power to sign one.

"It's only the secretary of state who can be responsible for the decision to make the order," he added.

That level of authority was required to ensure the process was legally valid, said the barrister.

'End of the matter'

Counsel for the Public Prosecution Service argued that a long-established legal doctrine allowed other ministerial figures to lawfully authorise Mr Adams' internment.

He argued that the Carltona principle covered those for whom the secretary of secretary has responsibility.

"If a decision is made by an official in the department for which the secretary of state is politically accountable to Parliament, that's the end of the matter - that's what Carltona says," he told the court.

The barrister said the onus was on Mr Adams' lawyers to try to "oust" that principle.

"There's nothing in the wording (of the legislation) which forces the court to that conclusion," he claimed.

Judgment was reserved, with Lord Chief Justice Sir Declan Morgan, who heard the appeal with Sir Ronnie Weatherup and Sir Reg Weir, saying: "We will want to go and reflect on it."

- Published18 July 2017