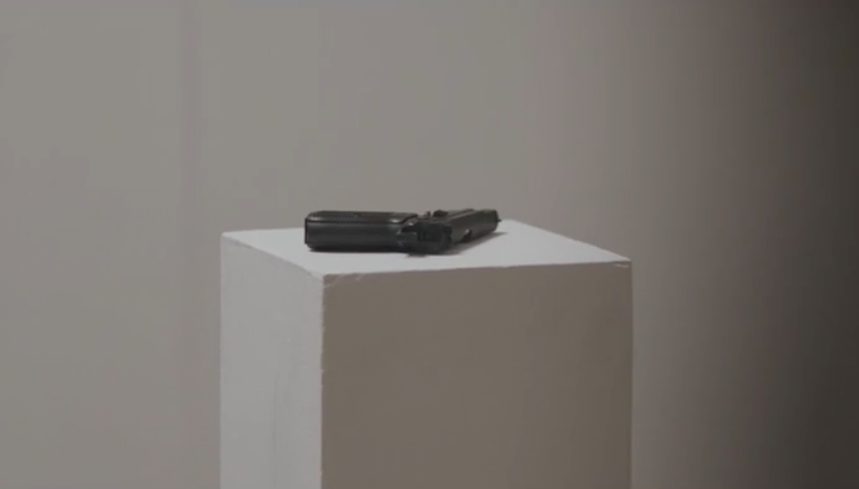

After shootings, guns in the UK are often passed on, traded, rented or hidden away.

That is how this gun travelled across a major city without being seized, and was used in multiple, unrelated shootings.

Some of these shootings remain unresolved.

The police give every gun they know about a different number, so that they can be tracked and monitored depending on their own unique characteristics.

This particular gun is a black CZ 75 semi-automatic pistol made in the Czech Republic.

Investigators have called it Gun No 6.

Now, almost a decade after the firearm was last used, an in-depth ΒιΆΉΤΌΕΔ Two documentary has tracked its journey.

"The history of Gun No 6 starts on the streets of Birmingham one night at about 3am, when shots are fired."

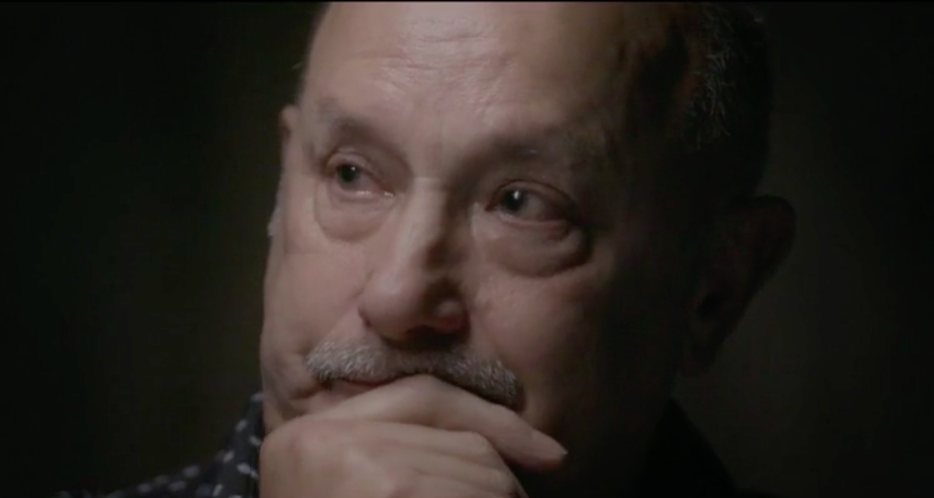

Andy Hough was Detective Chief Inspector of West Midlands Police when Gun No 6 first appeared. He describes the night of 23 February 2003.

Police receive an anonymous call about a shooting outside a club. When they arrive on the scene, they find two bullet casings.

But no-one - neither the witnesses, nor those who were shot at - comes forward.

The only person who actually knows what happened, and why, is the person who pulled the trigger

"From about [the year] 2000 onwards, we had started to see an escalation in gun-related homicides," Andy says. "And we had a community that wouldn't talk to us because they were frightened.

βWe had no known witnesses, there was no scientific material other than the bullet casings, there was no CCTV, there was no telephone evidence, and most importantly, there was nobody coming forward to say, 'In the early hours of this morning somebody tried to shoot me.'

"The only person who actually knows what happened, and why, is the person who pulled the trigger."

Nobody who has fired Gun No 6 has ever told police where to find it. They're either unknown, or are currently serving life sentences after using the gun to murder their victims.

Filmmakers Zac Beattie, Georgina Cammalleri and James Newton have spent two years diving into the gun's disturbing history.

"The idea for the film came from an old newspaper article about a different gun that police realised was used in seven different crimes in London," Zac explains.

"We were fascinated to learn that you could follow the journey of a gun, and potentially the lives it touched."

After working with experts at the National Ballistic Intelligence Service (NABIS), they were "shocked" to learn about Gun No 6 - which had been "used in more shootings and murders than any other".

"We want to see if, by telling the story of this one gun, we could tell a story about something bigger - about violence, and about the society we live in."

But the story of Gun No 6, and all illegal guns in Britain, doesn't start with the first shooting.

Really, it starts with Dunblane.

Guns in Britain

What later came to be known as the Dunblane Massacre changed everything. It was the worst school shooting ever carried out in Britain, and even now the word "Dunblane" is synonymous with heart-wrenching grief.

Less than two years later, the had been amended to ban all handguns from private use.

Gun control in the UK is now among the . Handguns are banned, and without going through a strict licensing procedure, it is illegal for a person to sell or be in possession of any firearm.

A child lays teddy bears at a memorial in Dunblane in 1996 (Picture: Getty Images)

So how do weapons like Gun No 6 end up on our streets?

Helen Poole, a firearms expert from the University of Northampton, says that there are a number of ways that this happens - one of which is thefts from legal gun sellers and owners.

These gun sellers, Helen explains, usually sell "deactivated antique guns to history enthusiasts" - that is, old guns that have been modified so that they can no longer shoot. But in the wrong hands they can be reactivated relatively easily, making them potentially deadly again.

According to the latest stats, own a firearms or shotgun certificate. It's estimated that around 600 guns a year are stolen from legal gun owners, most of which inevitably end up on the black market.

Another way guns come into the country is through large shipments from abroad.

A replica of Gun No 6 (Picture: ΒιΆΉΤΌΕΔ Two)

Simon Brough from the National Crime Agency (NCA) explains that intercepting these shipments is a delicate collaboration between his agency and Border Force.

"Dover is the UK's largest port, and already this year we've had seven operations there that have involved the seizure of firearms and ammunition," he says.

"What we hope is that our work makes the prospect of smuggling guns across the border an incredibly risky one for criminal gangs."

Helen agrees, adding that the NCA and Border Force are "particularly good" at intercepting shipments of guns.

Among these hauls, she adds, will be deactivated guns that "have often originated in post-conflict regions, including some countries in the western Balkans". Many will have been modified so they can shoot again.

These weapons are usually military-grade, and their import into the UK is organised by large criminal gangs.

The final way people get their hands on guns is by buying the parts separately online - often, but not always, on the dark web - and building the weapons themselves at home.

And once a gun is in the country, it remains in circulation until it's found by the police.

Firearms are dangerous weapons and the State has a duty to protect the public from their misuse. Gun ownership is a privilege, not a right

But Helen explains that guns don't need to be sold on the black market in order to change hands and be used in different, seemingly separate crimes.

"I previously worked in DNA and fingerprinting, and at the time there was a big issue with vehicles that were essentially 'community cars' for use in crimes," she says.

"In the same way, there are possibly guns that aren't being sold between people, but are 'community guns' - so if you need to get hold of it, anyone in that community will know to go to the last person who used it."

Helen mentions a pistol - a Beretta 9000S - that was seized by investigators in Merseyside last year. It was discovered when police raided the home of Adam Bigley, then 24, and found the gun hidden in a bathroom behind some pipes. The gun was still loaded with four live rounds. The serial number on the side of the gun, which is one way a firearm can be traced, had been scratched out.

But despite the missing serial number, investigators could confidently link that gun to 19 non-fatal shootings. There was that Adam was directly involved in any of the actual shootings, but he was sentenced to six years and nine months in prison for possession of a prohibited firearm.

Officers could track that firearm because, when a gun is fired, it leaves unique marks on the casing of the ammunition. Andy says this is like βa fingerprintβ.

This is how investigators were able to track the journey of Gun No 6. In the space of less than two years, after the first incident on Proctor Street, they found its 'fingerprints' at seven more non-fatal shootings.

βYouβve got two things when you fire a gun,β Andy explains.

βYouβve got the rifling [spiral grooves that add a spinning motion to the bullet] within the barrel, and youβve got where the hammer of the gun hits the back of the bullet.

"There are then two sets of marks - one along the length of the cartridge, and one on the circular bit on the back of the cartridge.

βThese both leave distinct markings, because each gun is slightly different. We donβt always recover the gun itself, but by looking at these prints we can tell when bullets in different shootings were fired from the same weapon.β

Gangs in Birmingham

Gun No 6's story is set against a backdrop of escalating gang violence in the UK's second biggest city.

For at least a decade before the gun made its debut, the streets of Birmingham had been terrorised largely by two gangs: the Burger Bar Boys and the Johnson Crew.

The origins of these two gangs are unclear - but by most accounts, they originated in the mid-1990s.

the crews were formed when people banded together to form vigilante groups, protecting their communities from targeted attacks by racists.

Other have it that the groups simply used to all be mates, before an argument over a bet on who won a game of Streetfighter on the PlayStation.

Either way, things between them became vicious. The groups split down the middle according to their postcodes and violently defended their territories.

Two gangs formed from this schism - the Burger Bar Boys, also known as "The Burgers", and the Johnson Crew, aka "The Johnnies".

Both were named after their regular meeting spots in Handsworth, north-west Birmingham, in the mid-1990s: The Burger Bar on Soho Road, now closed, and Johnson's cafe on Heathfield Road in nearby Lozells, which has also since closed down.

The city was quickly divided up into territories, according to who had the right to sell drugs where.

The Burgers were said to be wealthier and better organised, with a much deadlier collection of weapons. But the Johnnies, on the other hand, were larger - they had more members, and had allegiances with other splinter gangs in the area.

In 1995, the two gangs were already notorious among police in Birmingham for being involved in drug dealing, robberies and kidnappings, when shootings started happening outside the city's nightclubs and community centres.

Prompted by the unsolved murder of Corey Wayne Allen, 27, in 1999, West Midlands Police launched to fight gang violence in Birmingham - in particular, the city's growing gun culture.

Ventara did little to quell the violence, however, and the shootings continued to escalate. Across England and Wales, gun crime had in the two years following the 1997 handgun ban.

Things came to a head in December 2002, when Burger Bar member Yohanne Martin while waiting at traffic lights in West Bromwich, a suburb north-west of Birmingham. Yohanne's brother Nathan, also a Burger Bar member, was convinced that the Johnnies were behind the killing.

On New Year's Eve, 2002, Nathan and other Burgers bought a red Ford Mondeo. Less than 48 hours later, they drove it up to a New Year's Day party at a hair salon in Aston and with a Mac 10 machine gun - a gun first developed as a military weapon in the mid-'60s.

They were trying to hit a group of young men standing close by - one of whom was an alleged member of the Johnson Crew.

Charlene Ellis, second from left, and Letishia Shakespeare, far right, were killed in the shooting (Picture: ΒιΆΉΤΌΕΔ Two)

But instead, they shot and killed two young girls - Charlene Ellis, 18, and Letishia Shakespeare, 17.

This horrific shooting made headlines across the UK.

The deaths of Charlene and Letishia were fresh in everyone's minds when, less than three months later, Gun No 6 first appeared on the streets of Birmingham.

Two years later, Nathan Martin, Michael Gregory, Rodrigo Simms and Marcus Ellis - Charlene's half-brother - were convicted of the girls' murder and with a minimum recommended sentence of 35 years.

After the sentencing, the victims' mums shouted "justice" as they drove away from the court.

Shooting #9: The nightclub killing

Ishfaq Ahmed worked as a doorman at a nightclub called Premonitions in Birmingham city centre.

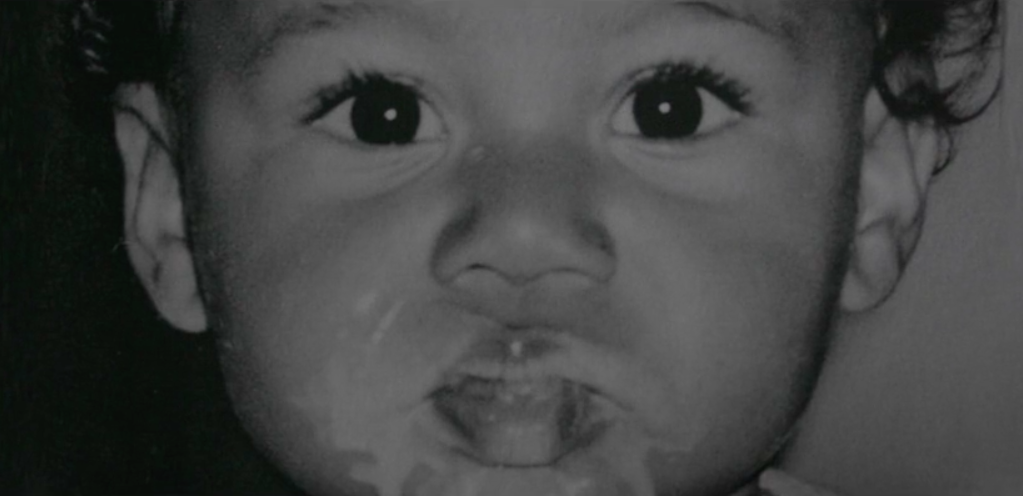

On the cold winter night of 20 November 2004, he kissed his partner Penny and baby daughter Aneesah goodbye - as he always did before heading into work.

It seemed like a normal Saturday night. People were out, drinking, dancing and having a good time.

That was until about 03:30. A group of men linked to the Johnson Crew were "rushing doors" in the local area - pushing and forcing their way into clubs. Ishfaq jostled with them, trying to do his job and stop them from getting in without paying.

After a struggle, the Johnnies appeared to be walking away - before they turned around again to shoot. Ishfaq was shot three times in the back by two 9mm handguns - one of which was Gun No 6.

Ishfaq was killed by a bullet that entered his shoulder, travelled through his chest, and shattered the main blood vessel in his abdomen.

He was 24 years old.

Ishfaq Ahmed will never get to see his daughter grow up (Picture: ΒιΆΉΤΌΕΔ Two)

Penny remembers the last time she ever saw her partner.

Their daughter, Aneesah, was only about 18 months old at the time.

"I can remember him dropping me and Aneesah off [at home], and I came up the stairs and looked out the window," Penny says. She saw him sitting outside in his car, looking back up at her.

"Whereas before he'd just speed off, this time he wasn't - he was just sat there.

"My home phone was ringing, it was my friend Melanie. I actually said to her: 'He's looked at us like he's never going to see us again'. I just had this horrible feeling."

In the middle of the night, Penny started to worry about Ishfaq.

She had woken up to feed Aneesah and was surprised to see that Ishfaq wasn't home.

Despite telling herself that he must be OK - that he always comes home safely - she couldn't shake the niggling feeling that something terrible had happened.

Then she got a phone call.

"I woke up to get Aneesah a bottle and... he wasn't there," she says. "And within five minutes my phone was ringing. It was his dad phoning me to tell me what had happened."

Penny started to think of all the things he would miss out on - all the little moments they had looked forward to together.

"He wouldn't see Aneesah grow up," she says. "Her first day at school, he'd wanted to take her - knowing [he'd miss that] was hard."

"It's all gone. All because of one bullet."

Ishfaq, Aneesah and his partner Penny (Picture: ΒιΆΉΤΌΕΔ Two)

The following year, in December 2005, six men were convicted of killing Ishfaq in the Bristol Street shooting.

Dean Smith, William Carter, Carl Spencer, and Michael Christie - allegedly all part of the Johnson Crew - along with Leonard Wilkins and Jemal Parchment, of murder.

During the two-month trial, an armed convoy brought the defendants to and from court every day.

[A] gun was fired and killed a blameless man, for no other reason than that he was doing his duty as a doorman at a nightclub

They were all jailed for life, with a stipulation that they must serve a minimum of 30 years.

Sentencing the killers, Mr Justice Mitting told them: "[A] gun was fired and killed a blameless man, for no other reason than that he was doing his duty as a doorman at a nightclub - and caused you loss of face or annoyance, or both."

Penny found out Ishfaq had died in the middle of the night (Picture: ΒιΆΉΤΌΕΔ Two)

Now, speaking 13 years later, Andy Hough reflects on the shooting.

"The investigation into the murder of Ishfaq Ahmed was a tremendous piece of policing work," Andy says.

"It involved detectives from the then-Murder Investigation Unit working with the local police and the local community to bring six notorious criminals from the Johnson Crew to justice.

"However - we didn't recover Gun No 6."

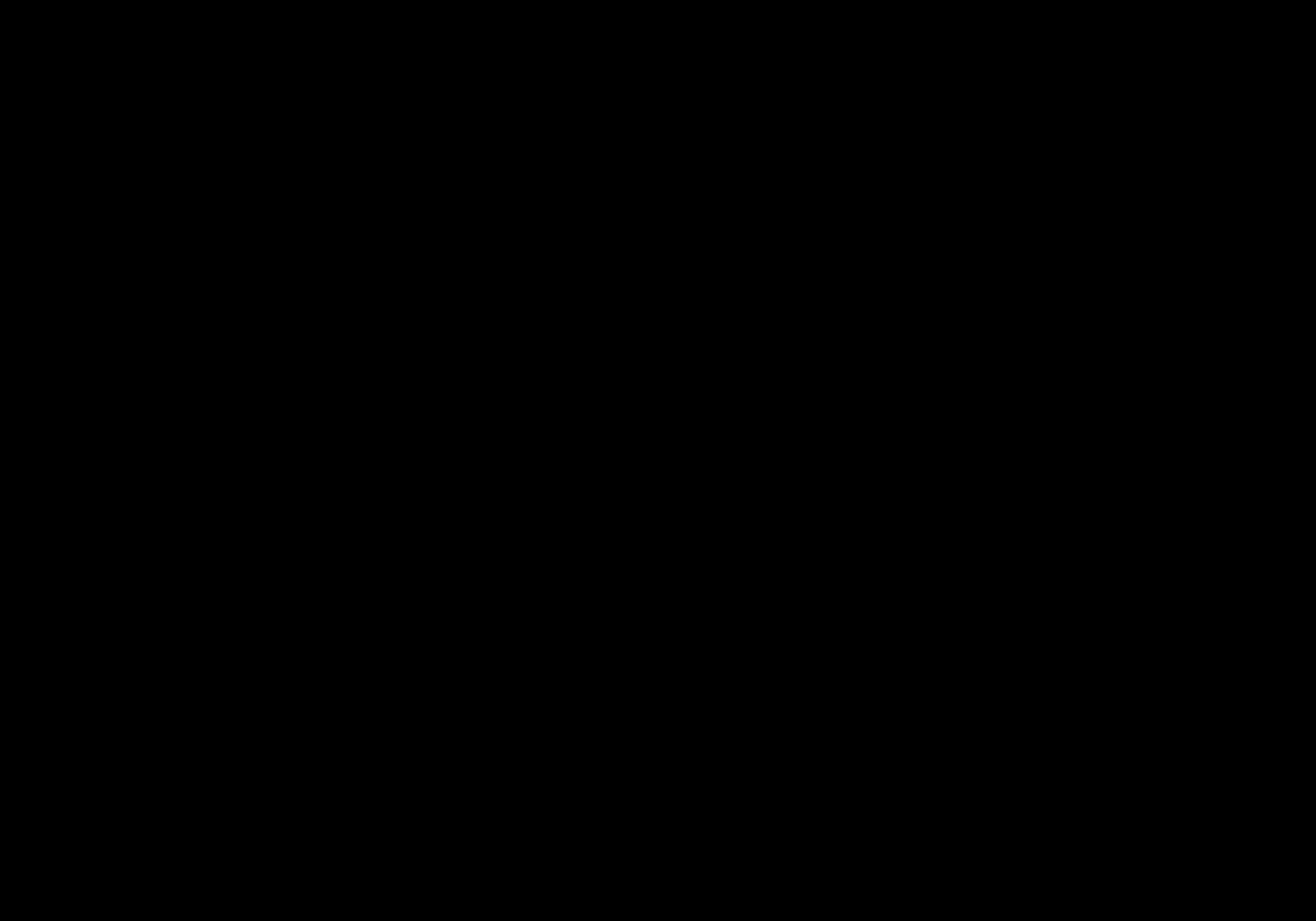

Shooting #10: the 'execution'

It had been eight months since Gun No 6 was used. But on 23 July 2005, it reappeared - this time in the hands of a man from London.

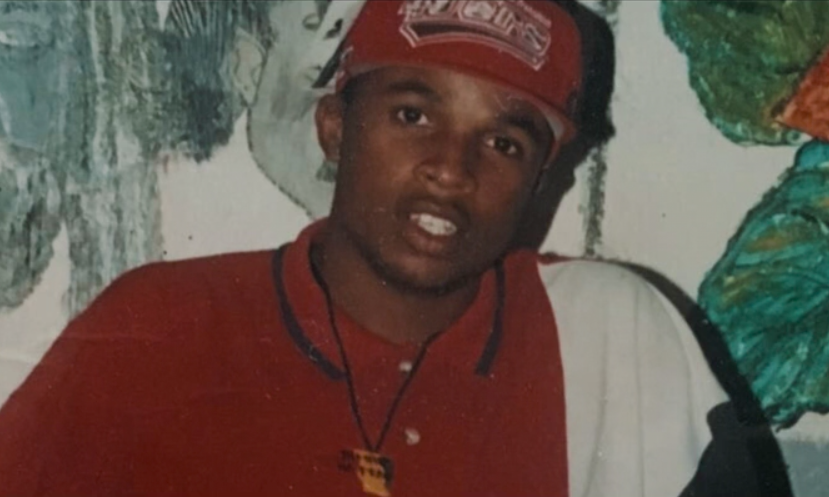

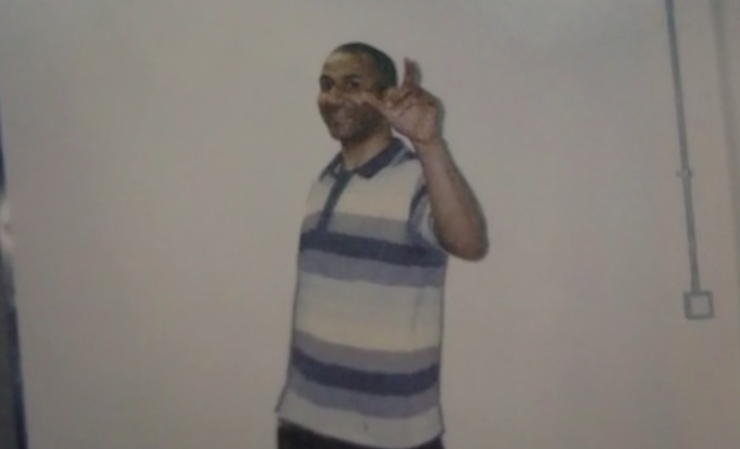

That man was , a 23-year-old drug dealer. He was looking for Andrew Huntley, a 31-year-old dad.

He found him waiting to get into a nightclub - and immediately started to chase him. Andrew tried to run away.

We are brothers. We do not have to live like this

Terrified, Andrew ended up kneeling on the ground beneath a railway arch on Heath Mill Lane in Digbeth, raising his arms in apparent surrender and begging Kemar for mercy.

Kemar then opened fire on Andrew and shot him twice in the head - killing him in cold blood.

According to a witness, Andrew's last words were, "We are brothers. We do not have to live like this."

The shooting would later be described by judges as an "execution".

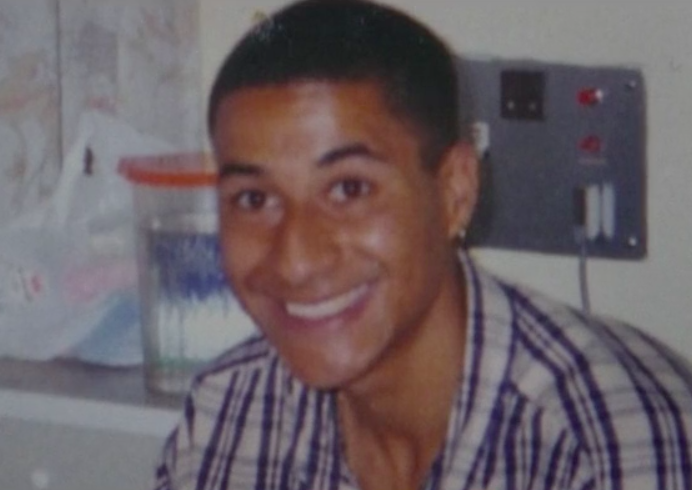

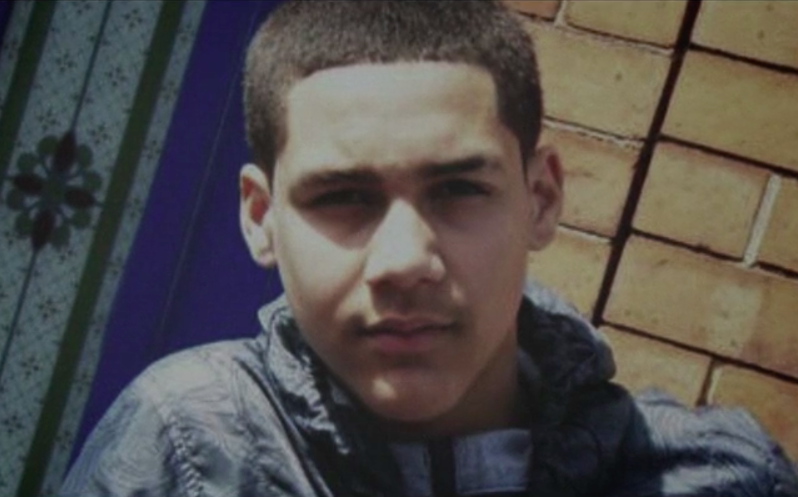

Andrew Huntley, pictured as a young man, was shot in cold blood (Picture: ΒιΆΉΤΌΕΔ Two)

Eight months later, Kemar Whittaker went on trial for killing Andrew and was convicted after just two weeks. He was sentenced to life imprisonment, with a minimum of 30 years.

"There was minimal argument before you executed him in cold blood when he was kneeling on the ground," Mr Justice Hughes told the killer.

"You had access to a weapon that was in circulation on the streets being used for crimes just such as this."

That weapon was Gun No 6.

Andrew had a young son, Akeem.

"My dad was a happy person," Akeem remembers. "He liked fashion, he liked to dress well. As soon as he smiled it's like he gleamed up the whole of the room - it was like a light."

Now aged 20, Akeem has become cynical - the death of his dad altered his worldview. But when he was a kid, he had big dreams.

"When I was five years old, my dad started taking me to football," Akeem says. "I got into a team, and started taking it more seriously when he died.

"But then I just stopped playing. As you get older you realise the dreams you have aren't always going to come true."

He still carries around the memory of his dad, keeping photos of him on his phone.

"You won't see me show it but the emotions are still there. I think about my dad every day... because if not [for what happened], my life would be different."

After Andrew's murder, Gun No 6 disappeared for four years - and Andy Hough believes he knows why.

βWhen a gun is used in a murder, it becomes βhot',β he says. βThat is, no-one wants it. If youβre caught with a gun thatβs linked to a murder, youβll have to answer a lot of difficult questions.

βSo the owner will try to get rid of it as quickly as possible. Sometimes they get buried in gardens or graveyards, other times they get passed on to people who arenβt within their circles at all.β

And so Gun No 6 was off the streets, for a while at least.

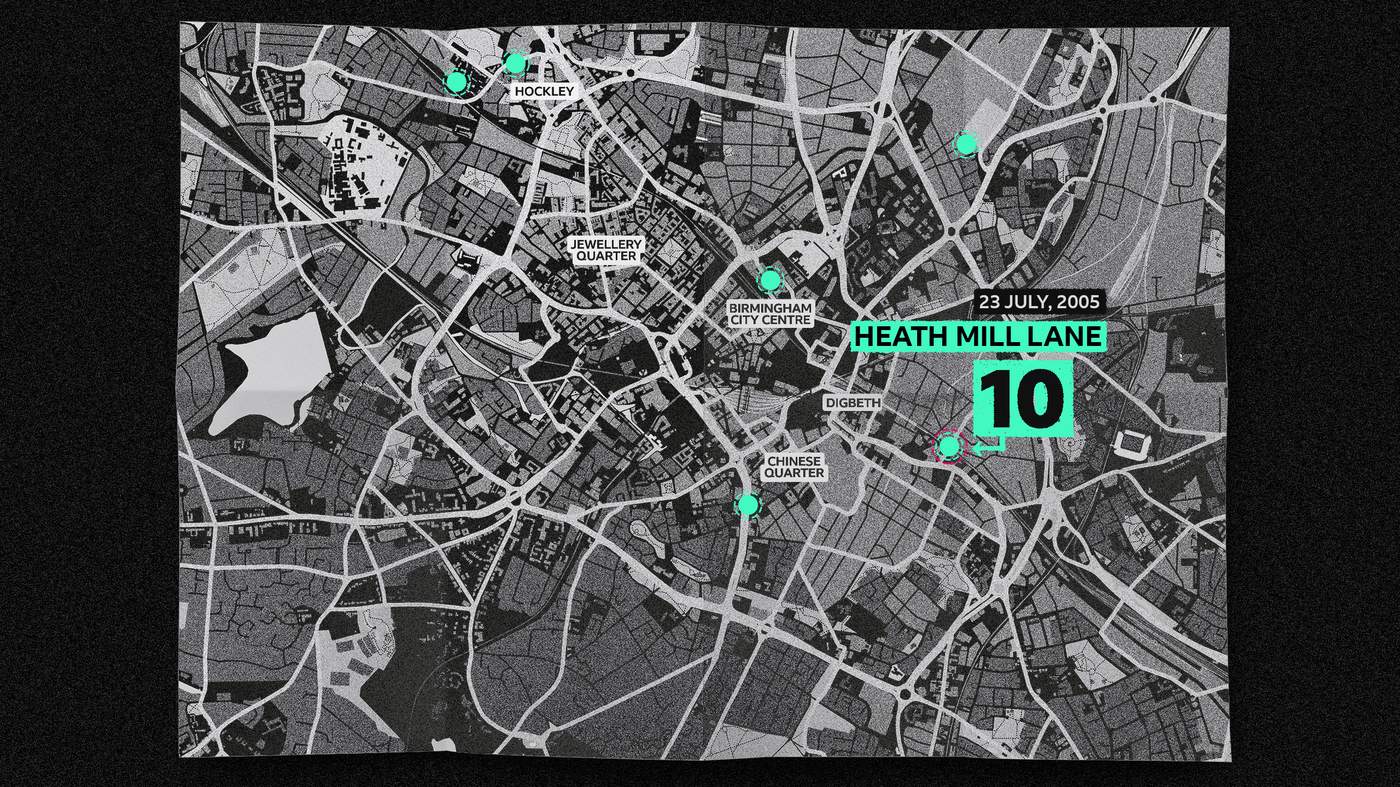

Shooting #11: The Post Office murder

Four years after the murder of Andrew Huntley, Gun No 6 reappeared.

This time, it was in the hands of a known criminal, Anselm Ribera, who held up a Post Office in the quiet village of Fairfield - about 45 minutes' drive from central Birmingham.

"We used to open at 7am so it would give me about a quarter of an hour to do all the papers and that," says Ken Hodson-Walker, who lived above the shop with his wife and two sons.

As Ken was opening the shop, his wife, Judy, told him that she was just popping upstairs to sort some bits and pieces out.

Remembering that morning, on 9 January 2009, Judy says: "To this day I bitterly regret that I didn't look out the window - because I would have seen them getting out of the car."

She's referring to a group of armed robbers who, just over an hour later, would force their way into the small corner shop, hold them up at gunpoint, and plunge their family into tragedy.

"They came in," Ken recalls. "One of them had a big sledgehammer. The other one had a gun, which I didn't really believe was real.

"There was a young girl in there - she saw them come in and she absolutely screamed the place down."

The shopper's screams were heard throughout the house, including in the family bedrooms. Judy and her eldest son Craig, 29, immediately ran out into the hallway.

They knew something terrible was happening downstairs.

At about 08:20 Judy ran into the shop, followed closely by Craig - who, in his panic, had run out wearing only his boxer shorts.

Realising that they were in the middle of a robbery, Craig held his mum's shoulder and pulled her back, away from the danger. He then reached over and picked up a cricket bat.

A fight ensued. Craig tried to hit the robbers with a cricket bat while his mum retreated behind a shelf, and his dad tried to fight the attackers off from behind.

Then - a gunshot rang out.

Ken recalls all the vivid details of what happened next. "Craig was shot. He said, 'They got me'. I heard the cricket bat drop on the floor, so I went round and picked it up.

"The middle [robber] grabbed hold of the gunman and pulled him round the corner - then they shot me in the leg. It bloody hurt. It hit my bone right on my knee.

"They obviously wanted to do me more harm, so they grabbed all these metal shelves, threw those onto me, and they proceeded to jump up and down on the shelves - which I was stuck underneath. They did that quite a few times."

Then the robbers left.

Ken recalls the day in vivid detail (Picture: ΒιΆΉΤΌΕΔ Two)

The shop was completely turned over. Different products, normally meticulously laid out by Ken and Judy, were strewn across the floor.

Fearing that his son was badly injured, Ken pushed the shelves off his body, pulled himself up into a seated position, and used his arms to drag himself along the floor towards Craig, his leg bleeding profusely.

Pushing through the throbbing pain coursing through his body, Ken pulled himself around the corner to where he knew Craig had been hit. He saw him lying still in a large pool of blood.

Ken dragged his increasingly weak body the final distance towards Craig and touched him gently, full of desperate hope that his son was still alive.

A cold chill passed through Ken's body.

"I knew he was dead."

"I was 19 when I first met Anselm," his former partner, Alison Cope, says. "He was 18."

Far from the killer he would later become, at that time she says he was "quiet, shy and unsure".

To her at the time, she says, he seemed like a caring and kind-hearted young man.

"I was just happy to have this person in my life."

The two of them moved in together "very quickly", and just a few months later, 21-year-old Alison found out she was pregnant.

It was the mid-β90s.

"During that pregnancy, Anselm was arrested and charged with a burglary, and sent to prison for just a few weeks," Alison remembers.

But although his sentence was relatively short, she says, it changed him.

"I remember him coming out of prison with more knowledge of crime than he'd had going in."

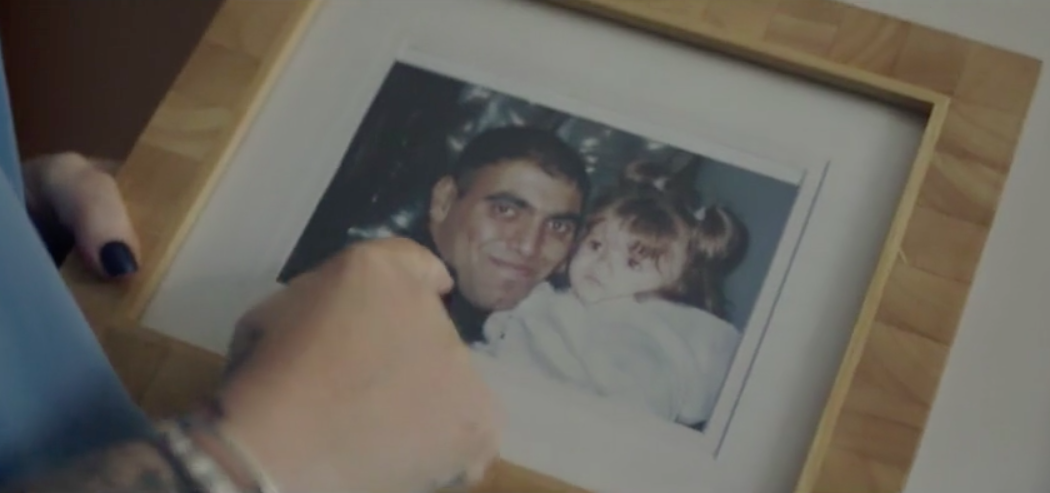

Alison and Anselm's son, Joshua, as a baby (Picture: ΒιΆΉΤΌΕΔ Two)

On 10 August 1995, Joshua Ribera was born.

When she looked at his face for the first time, Alison was struck by how much he looked like Anselm.

This tiny newborn was his dad's exact double. And she was filled with boundless, overwhelming love for him.

Josh's first few months were happy. The young family loved to chat, play together and spend time with each other. The young baby was just learning to smile and laugh.

But it wasn't long before things started to change.

When Josh was still young, Anselm was arrested for another burglary. This arrest ended up becoming the turning point in their relationship.

"I said to him, 'Listen, this isn't really what I want from a relationship. I need you.' But Anselm's need to live that life was far greater at that point than it was to be with me.

"So I left him - and the relationship was over."

Alison and Anselm with their son Josh (Picture: ΒιΆΉΤΌΕΔ Two)

When Josh was still young - about seven years old - Anselm was arrested and charged with an armed robbery. After a trial, he was convicted.

"It was quite a lengthy sentence," Alison says.

But it was another two years before she was told what he had actually been convicted of.

She hadn't imagined that her former partner, who she had once been so in love with, was capable of something as serious and violent as armed robbery.

"I was told it was a warehouse theft. So even at that point I didn't realise the road he was going down was so serious."

Anselm went to prison for armed robbery in 2002 (Picture: ΒιΆΉΤΌΕΔ Two)

Anselm was released from prison in 2007. This was when he started spending time with two known petty criminals, the Morrissey brothers. The three of them plotted to hold up a small, family-owned post office in Fairfield.

That was when he killed Craig Hodson-Walker in cold blood.

But it wasn't just Craig's family that was torn apart by the killing. Anselm destroyed his own family too.

Josh Ribera, who was only 13 at the time, struggled to come to terms with the fact that his dad could be a murderer.

Alison remembers the moment when her mum called to tell her Anselm had been arrested and charged with the murder of a young man in Fairfield.

Her immediate thought was for Josh. She was filled with worry about how he would take the news - and started panicking in case he saw it in the newspapers first.

She rushed out of the house to find him, so she could break the news gently.

Alison eventually found him - he was ice skating. She brought him home, but when she told Josh his dad had been arrested again, she was met with a defensive tone.

"For what?" he asked, shrugging it off as though it didn't bother him either way.

But it did bother him.

"When I said the word 'murder', Josh just demolished the front room. He smashed everything up. He was crying, he was angry."

That was when, as Alison describes it, "the nightmare began".

Josh as a baby, left, and dressed as a policeman, right (Picture: ΒιΆΉΤΌΕΔ Two)

"He was devastated," she says. "His dad was 'the scum of the earth', as quoted in one newspaper. His dad had destroyed a young man's life."

After that, Alison says that Josh "went through a really difficult time, and just kept getting into trouble".

But after a few years, things started getting better.

When he was around 16, Josh discovered a passion for music. He threw himself into producing music - rap and grime - putting his heart and soul into every song he wrote.

Going by the name Depzman, Josh became a big success - and was tipped to be the next big thing in grime.

By the time he was 18, he was doing shows across the UK and flying out to Europe to perform. His album got to number one in the hip hop charts, and appeared on ΒιΆΉΤΌΕΔ Radio 1Xtra.

Josh stood out because he rapped about positive things. Some of his songs were about how much he loved his mum, for example. Others, about how he missed his dad.

With the money he got from the sales of his album, he bought his grandma flowers - tweeting photos with her to inspire his followers to show they loved their grans too.

It worked - his replies were flooded with fans tweeting him similar photos with their own grandparents.

A photo Josh tweeted, with the caption: 'Grandma means the world to me' (Picture: ΒιΆΉΤΌΕΔ Two)

On 20 September 2013, Josh went to a concert in the Selly Oak suburb of Birmingham. It was a memorial concert dedicated to a friend of his, who had been stabbed and killed exactly one year beforehand.

"He left me here that evening," Alison says. "His last words to me were, 'I love you mum.' Then he gave me a hug and a kiss, and said, 'I'll see you later.'"

At that concert, Josh was stabbed once in the chest.

The knife attack proved fatal. He was rushed to Solihull Hospital, and passed away in the early hours of the morning.

Now, Alison dedicates her time to preserving Josh's memory, giving talks at schools to prevent other kids from going down the same path as her son's killer.

Maximum damage

"The 9mm parabellum [firearms cartridge on Gun No 6] was designed primarily for military use," Gareth Cooper, Ballistics Material Examiner for West Midlands Police, says.

"It's a penetrating round, above all else, which is designed to increase the rate at which the energy is dumped into the target - causing an increased rate of tissue damage.

"But effectively, pistol bullets all work by haemorrhagic effect. It's a question of rupturing as much body tissue - preferably critical body tissue - as possible."

In other words - Gun No 6 is a dangerous killing machine.

"A weapon like this on the streets is a worrying thing to us."

This gun has ruined lives and ripped families apart - both of the victims, and of those who pulled its trigger.

All of these brutal shootings were in some way connected by this one handheld weapon.

Gun No 6 has never been recovered.

Watch 'Gun No 6' on ΒιΆΉΤΌΕΔ iPlayer now.

If you've been affected by any of the issues raised in this article, help is available .

This article was updated on 06 December 2018