We've updated our Privacy and Cookies Policy

We've made some important changes to our Privacy and Cookies Policy and we want you to know what this means for you and your data.

Cycling the length of the Dakota Access pipeline

Image source, Martin Eberlen

In July last year, Martin Eberlen travelled from his home in London to the city of Stanley, North Dakota. Then he began to cycle. His route followed the length of the Dakota Access pipeline, the controversial pipe that transports some 470,000 barrels of crude oil a day across four states. Here, in his words, are the stories he found along the way.

It was an unconventional journey that took me to parts of the US tourists rarely visit, through North and South Dakota, Iowa, and ending in Illinois.

Natural gas burns continuously in North Dakota, on many of the oil pads. The smell of rotten fish was overwhelming at some locations. However, you could not escape the heat.

The only real glimpse of the actual pipeline was the imposing valve stations. They dominated the landscape, usually sitting in a farmer's field.

They have been targets for vandalism by many protesters along the route. So, now some are guarded by private security companies. It is also not unusual for the occasional helicopter to pass by, keeping an eye on those below.

Image source, Martin Eberlen

Image source, Martin Eberlen

Rand Olson, of Stanley, worked for an oil company in North Dakota for almost 11 years. He now spends his time collecting relics from the automobile industry and creating sculptures from leftover scrap metal.

His back garden was full of flower displays constructed from old cogs and mechanical working parts, and large carbon-fibre animals. His pride and joy, however, was his penny-farthing, which he had placed on his front lawn, where he proudly posed for a portrait.

I had a long chat with Breeze in the car park of the Roosevelt Inn, Watford City. He works in the oil fields as part of a fracking team.

"I'm on $130,000 [Β£93,000] and I've only got a high-school education," he said. I was shocked at how much he earned, even though I knew there was big money in oil.

His life revolves around the job, starting with a 04:00 breakfast, followed by the 90-minute bus ride out to the oil wells, 12-hour working days and then the journey back.

It had been nearly five weeks since he saw his family in Mississippi. "I go home in two days. I can't wait," he said.

Image source, Martin Eberlen

Image source, Martin Eberlen

Image source, Martin Eberlen

Image source, Martin Eberlen

After attending several appearances demonstrations, waitress Jessica Fears of Ames, Iowa, was arrested stopping a lorry from entering a pipeline construction site near Pilot Mound.

"I was put in a holding cell for 10 to 12 hours," she said.

"They took my photograph, which was later bought for me as a present by a friend of mine."

Farmers Gary and Linda, of Jolley, battled against the pipeline company for several months, before their land was taken by compulsory purchase.

They lost approximately five acres (20,000 sq m) during the construction process.

The land has never fully recovered, and no compensation for the crop damage has been paid.

Gary and Linda welcomed me into their home. After several hours listening to their story, we drove out to the field to see the damage.

Image source, Martin Eberlen

Image source, Martin Eberlen

Image source, Martin Eberlen

Image source, Martin Eberlen

I was in my sleeping bag at dusk, in my tent at Little Missouri State Park, North Dakota, when the campsite host, Ruth, came over and persuaded me to head out for a tour of the oil pads, to see the flames lighting up the night sky.

She said the oil companies were able to do what they were doing because many landowners had sold their mineral, or oil, rights back in the 1970s.

"If they detect oil under your land, there's little you can do to stop them putting in another drill and extracting what they call 'black gold'," she said.

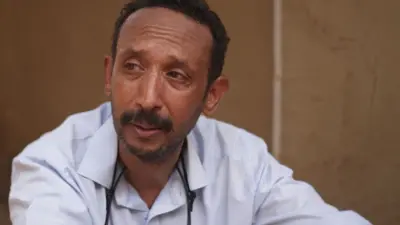

Saheed was carrying a Chinese takeaway back to his hotel after a 16-hour shift on a fracking team in the Bakken Oil fields. He lives in Stanley for up to two weeks at a time, working every day. He then takes six days off, using the time to travel back to Houston to be with his family.

Image source, Martin Eberlen

Image source, Martin Eberlen

Image source, Martin Eberlen

Elder Memmot and Elder McDougal are missionaries from the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints.

In Illinois, I was fortunate enough to stay with a Mormon family for the night, learning about their religion, as well as getting a guided tour of their church, which sits high up on a hill overlooking the Mississippi.

Any Mormons I met from then onwards were thrilled I had visited one of their founding churches.

I also stayed at motels, but developed mixed feelings about them. They became a place of comfort for a good night's rest, but that feeling could quickly descend into isolation and loneliness.

I reached the end of the Dakota Access Pipeline at the Patoka terminal, Illinois, on the 23 August 2017.

After propping up my bike against the fence, I made the decision to head north to the town of Vandalia, for a well earned rest.

Image source, Martin Eberlen

All photographs subject to copyright.

Top Stories

More to explore

Most read

Content is not available