We've updated our Privacy and Cookies Policy

We've made some important changes to our Privacy and Cookies Policy and we want you to know what this means for you and your data.

Dementia: The implications for the care system

- Author, Alison Holt

- Role, Social affairs correspondent, ΒιΆΉΤΌΕΔ News

One of the key challenges that the UK faces is how to care for the growing number of people with dementia.

According to the Alzheimer's Society, by next year there will be 850,000 people living with dementia in the country. By 2025 there will be more than 1m people who have the condition.

The charity estimates every three minutes someone new develops dementia. It is a condition that changes not just the life of that person, but also the lives of the family around them.

It takes skill and understanding to provide the care and support needed as the condition robs a person of the memories they have stored up over a life time and makes everyday tasks difficult. With the right support many people can live well with the condition, but the challenge for many families is getting the help they need.

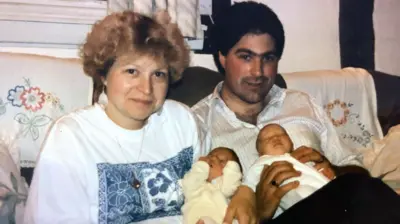

Andriani Adamou started developing the first signs of dementia when she was in her late fifties. To begin with her grown-up children cared for her at home, but then she started to believe they were imposters, intent on killing her. She spent six months on a psychiatric ward, but now has been moved to a care home.

"It seems to me that at the moment there is a bit of a lottery", her son Alex says. "If you have problems with your heart, or with your liver, or with your lungs, then it's a medical problem, and the care that you need for all the symptoms of those problems will be paid for by the NHS.

"But, if you have a problem with your brainβ¦It's deemed to be a social problem and therefore it's passed down to local authorities."

Financial decisions

Andriani's terraced house in London had to be sold to pay for her care, which costs in the region of Β£45,000 a year. The family thinks that it will be six or seven years before the money from the sale of her house runs out. These are the sort of catastrophic costs that some families can face.

The Alzheimer's Society estimates that if you include the unpaid care provided by families, the cost of caring for people with dementia in the UK runs to the equivalent of more than Β£26bn each year or Β£30,000 for each person with dementia. It says two thirds of the cost is met by families.

For Andriani's son, Alex, the money involved is just one more thing to worry about.

"Although the financial decisions are difficult and they're frightening because of the scale of sums involved, they always pale into insignificance compared to the human and emotional problems and decisions that you're having to make on a daily basis when you're looking after someone or when you're making decisions about their care and where they're going to be."

ΒιΆΉΤΌΕΔ Cost of Care project

Image source, Thinkstock

The ΒιΆΉΤΌΕΔ has launched an online guide to the care system for the over-65s. The "care calculator" covers both residential care and the support provided in people's own homes, for tasks such as washing and dressing.

Users can submit their postcode and find out how much each service costs wherever they live in the UK.

There is also a dedicated ΒιΆΉΤΌΕΔ Cost of Care website with news stories, explainers, analysis and video.

At the moment the family has no prospect of getting help from their local authority until her assets fall below Β£23,250. When the government's new care cap comes into effect in April 2016, they will get help sooner.

The ΒιΆΉΤΌΕΔ's care calculator estimates it will take two years and three months to reach the Β£72,000 cap. In reality she will have spent nearly Β£100,000 on her care during that time because living costs and any extra payments to the care home are not counted.

Once the cap is reached her local authority will pay the rate it sets for care, she will still be responsible for Β£230 a week living costs, as well as any additional charges. The sums are still high, but for her family it would take away some of the worry over how they cover the extra costs of care over the many years Andriani will need support.

Jeremy Hughes, the chief executive of the Alzheimer's Society, believes the Care Act reforms are a step in the right direction, but won't help most people who have to pay for care.

"In this country we have an army of unpaid carers - wives, husbands, daughters and sons - holding up a social care system on its knees."

"The failure of successive governments to invest in resources to help our most vulnerable is seen in the strain put on families, and these changes don't do enough to change that."

But the Department of Health insists the Care Act will make an important difference to people. A spokeswoman said: "We want to make sure those with dementia, their families and carers get the help they need. It's precisely because people face such unfair care costs that we are transforming the way people pay for care, capping the amount they have to pay and providing more financial help."

And they point to the emphasis the Prime Minister has placed on improving dementia care.

"To tackle this devastating condition, we are also doubling funding for research, pushing the NHS to improve diagnosis rates and post-diagnostic support, and focusing national attention on dementia like never before."

Top Stories

More to explore

Most read

Content is not available