By Jonathan Amos

The stench was unbearable. The hulking mass of dead dinosaur had lain on the sandbar now for over a week in stifling heat, half-buried among the decaying vegetation and sediment.

Some scavengers had tried to rip the putrid flesh from its bones, but the floodwaters kept washing over the site, dumping yet more mud and debris.

The open carcass of this 40-tonne giant was filling with all kinds of muck and beginning to disappear from view. The Earth itself was consuming the animal for geologic preservation.

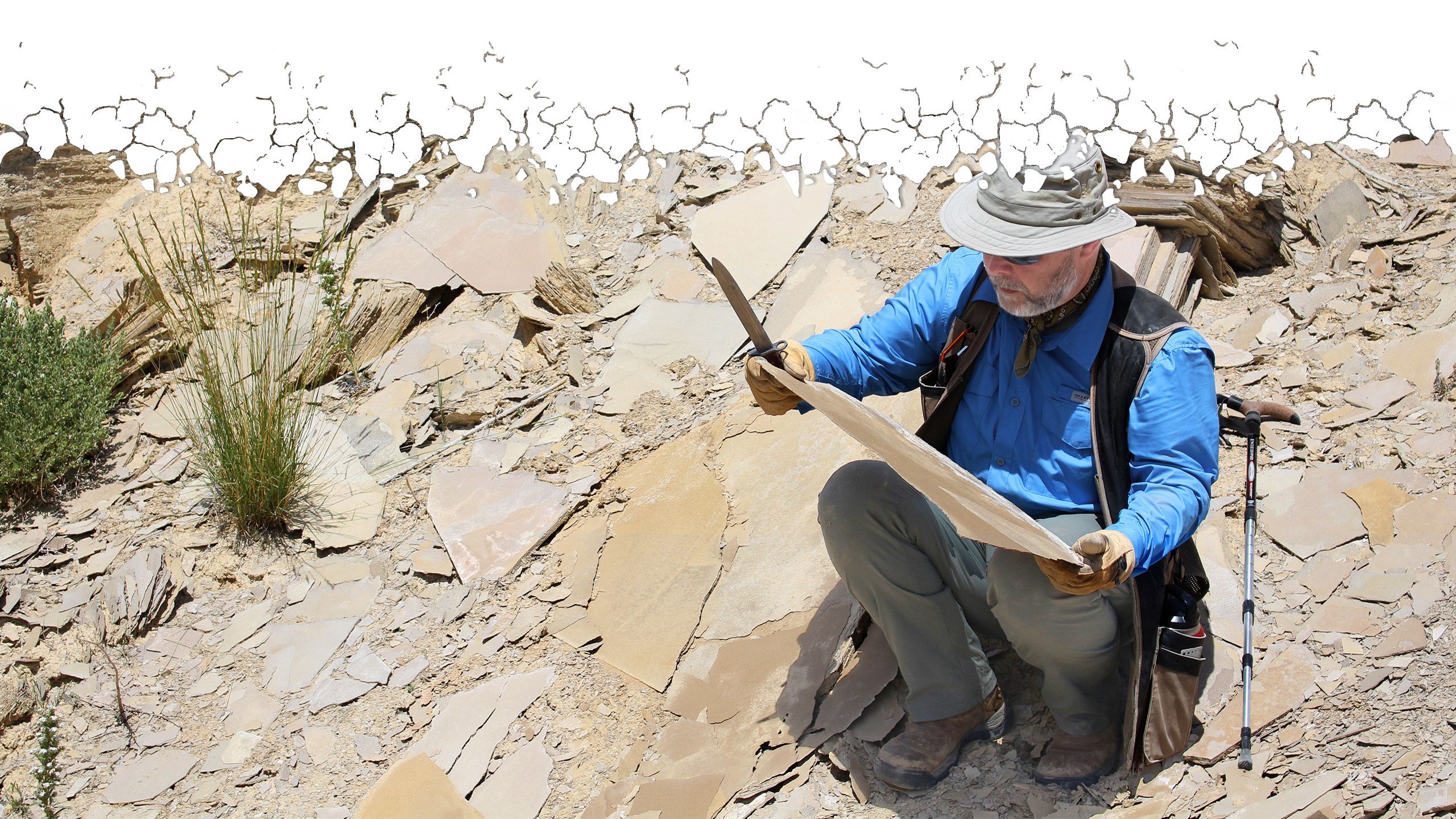

Fast-forward 150 million years and the University of Manchesterβs Phil Manning is on his knees in a tennis court-sized quarry in the "Badlands" of North Wyoming. He's narrating this Jurassic death story as he points to the tangle of fossil bones in front of us.

Remnants of leg, shoulder and spine have been worked proud of the sandstone. There's no doubting even to our untrained eyes that this is a sauropod - one of those huge plant-eating dinos that had a long neck and a long tail.

βThere's probably enough dinosaur material here to keep a thousand palaeontologists happy for a thousand yearsβ

Phil scrambles to his right to put his hand on a long stretch of brown-coloured rock. It's the fallen tree trunk that probably corralled the rotting beast and finally pulled it from the torrent, along with who knows how many other creatures now frozen in stone in this quarry.

Phil sits back on his heels. He's like the detective who's just walked in on a murder scene, assessed the available evidence and constructed an initial take on the final moments of horror.

"Just imagine: a fetid mess of deadness. Wonderful!" he grins. "It's rare that you get to see so many bones strewn in front of you like this. There are so many on this site it's like 'pick-up sticks'," the British scientist continues.

"There's probably enough dinosaur material here to keep a thousand palaeontologists happy for a thousand years."

Phil doesn't have quite that long. The Children's Museum of Indianapolis (TCMI), where he's also a scientist in residence, has signed a 20-year exploration lease on a parcel of Wyoming ranch land measuring one sq mile (260 hectares) in area.

Phil therefore has just two decades, the remainder of his career, to see what treasures can be unearthed. And he needs every bit of help he can get.

That's why, in addition to TCMI staff, he's called in Dutch colleagues from the Naturalis Biodiversity Center in Leiden, and UK associates from the University of Manchester, and London's Natural History Museum (NHM).

From the UK's perspective, "Mission Jurassic", as it's been dubbed, represents arguably the country's biggest dinosaur hunt in decades.

Phil and his co-chief scientist, Victoria Egerton, have organised the partners into work teams to systematically scrape back the layers of two pilot quarries. The participants are down on all fours, edging forwards in CSI formation, gently probing the pliable sediments with bayonets.

When you hit dinosaur bone, it sounds different, says NHM PhD student Joe Bonsor as he invites us to get in the dirt and "have a go". To illustrate his point, he picks up a piece and taps it with his knife to produce a kind of metallic chinking noise. The porous material also sticks hard to your tongue if you lick it, and again Joe demonstrates.

"Yeah, you have to be careful with that one; prairie dog poo has the same effect," quips his NHM supervisor Susie Maidment.

The positions of fossils are first marked with flags to show everyone where not to tread. Although, with some bones nearly 2m in length, theyβre pretty obvious.

Discoveries are then mapped and prepped for removal. Extraction involves digging a pedestal around the specimen before giving it a plaster-of-Paris covering. Itβs a messy job, but the hard βjacketβ, when it eventually sets, will provide protection for the ride back to the lab.

So far, Mission Jurassic has definitively identified at least four of those mighty sauropods. One could be 30m nose-to-tail; another perhaps 24m. There are some meat-eating allosaurs, too, waiting to be transported off-site.

These finds barely begin to describe the potential of what's here, however. And it's not just bones: it's also the trackways left by dinosaurs as they sploshed through mud, now turned to stone, and a profusion of fossil plants that record what these giants ate.

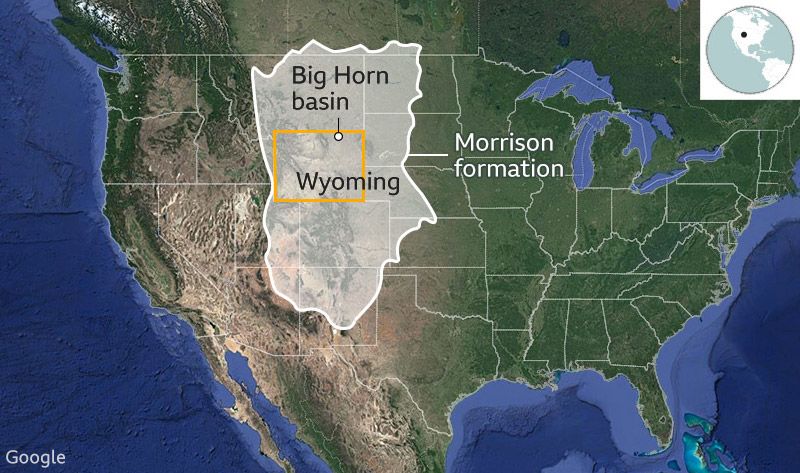

Dinosaur country

Wyoming boasts a breathtaking landscape: mountains and plains and everything in between. We're in hot, arid terrain in the Big Horn basin, close to the border with Montana.

Cowboys are mending fences and the prairie dogs are scuttling between the juniper bushes. Precisely where we are, we're not allowed to say. There are fossil thieves who would almost certainly try to raid the square mile if they knew its location.

We're even asked to switch off the geotagging on our phones and to avoid taking photographs that feature the horizon.

An overly revealing social media post might give the game away. Not that dinosaurs are hard to find in these parts.

βThe Morrison's got all the dinosaurs we knew when we were seven - Stegosaurus, Diplodocus, Brachiosaurus and Allosaurusβ

Wyoming is the US state where the "bone rush" really began back in the 1870s. As the railroad pushed west after the Civil War, reports began to emerge of a fossil bounty, of countless specimens literally falling out of the hillsides. Today, all self-respecting palaeontologists have to make at least one pilgrimage to the state during their lives.

From Pangea to the present day

From Pangea to the present day

Its geology captures a huge segment through the Mesozoic Era, the time when dinosaurs came to prominence. A particular draw is the Morrison Formation, a roughly 10-million-year sequence of rocks from the Late Jurassic Period.

This covers an immense swathe of the US western interior, but Wyoming hosts some of its most spectacular outcrops.

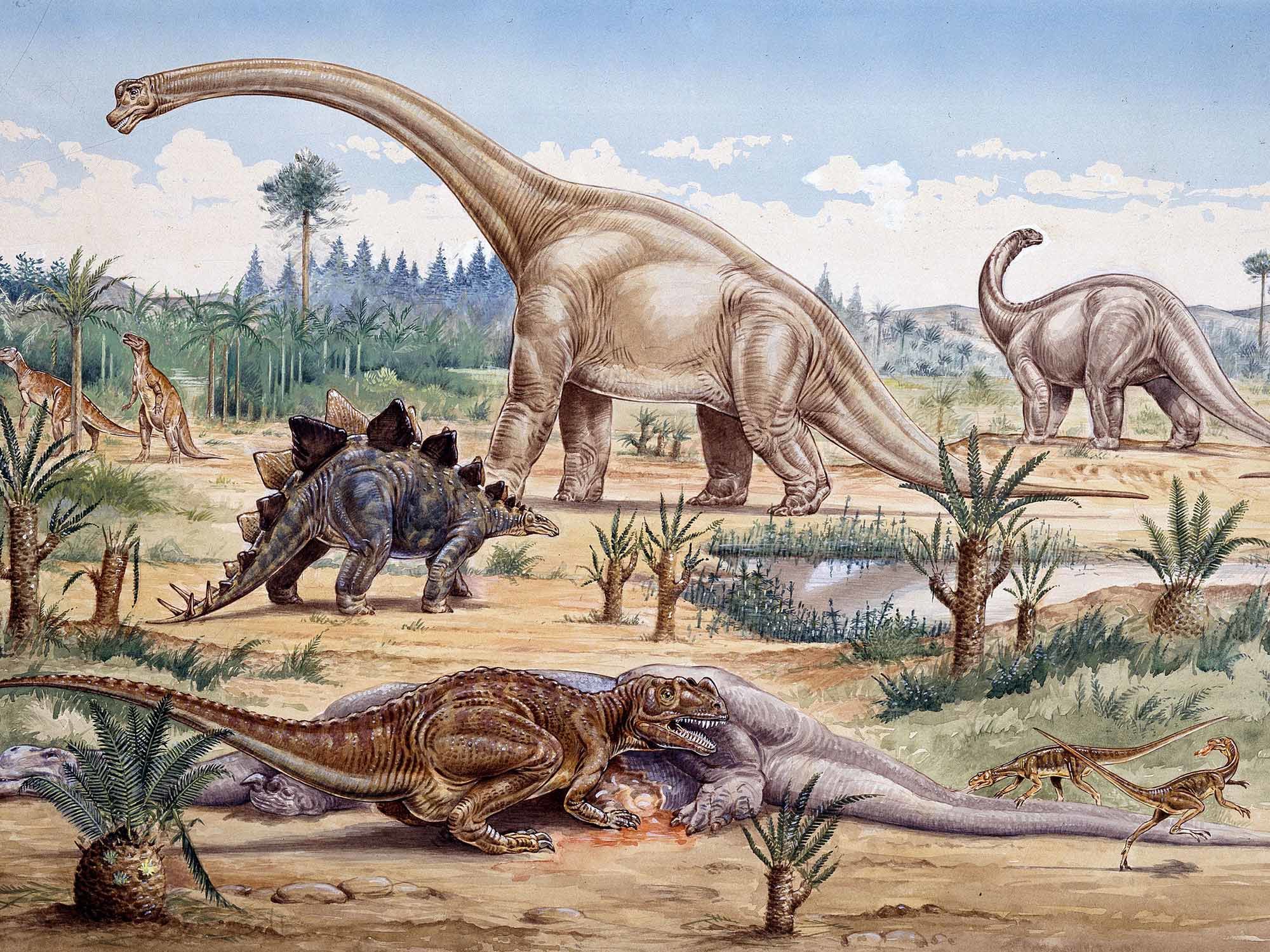

"The Morrison's got all the dinosaurs we knew when we were seven - Stegosaurus, Diplodocus, Brachiosaurus and Allosaurus. It's incredibly rich," says Susie Maidment who's come here in the hope of finding new species, or at least some slightly different versions of her childhood favourites.

What makes the Morrison so rich in fossils is the ancient environment it reflects. One hundred and fifty million years ago, Wyoming was anything but arid. It was semi-tropical and featured big rivers that meandered across vast plains.

"There was a lot of rain, a lot of storms - a lot of water being pushed around, and that means a lot of sediment being pushed around as well," explains local palaeontologist Jack Turnbull.

"Flash floods, mudslides, landslides - and all that moving sediment, every now and then, would bury animals and plants on a large scale. It's the only way we can explain the productivity of fossils that we find in the Morrison."

But as hazardous as this all sounds, it was also a time when the animals living on these wide river plains found great success. And this is evident in the size of the sauropods.

Only whales in Earth history have out-bulked these creatures, and the Late Jurassic is when their gigantism kicks in. That's something of a puzzle, says TCMI and Manchester scientist Victoria Egerton as she scratches at a crumbling cliff face and pulls out yet more of the Morrison's preserved vegetation.

"The plants are completely different from what we see around us today; flowering plants had yet to evolve," she explains, breaking open chunks of mudstone with her fingers to reveal fossil stems and twigs.

"In fact, these dinosaurs were eating things that we would consider to be very nutritionally poor - things like conifers (think 'monkey puzzle' trees), ferns, ginkgos, cycads and large horsetails. And we would love to be able to understand how they ate this food and still got to be the enormous sizes they evidently did."

In a circular way, part of the answer lies in the fact that they were so big. If you want to derive as much calorific value as possible from so impoverished a feedstock, you employ a giant fermentation tank. That's essentially what sauropods were: colossal fermentation tanks on legs. And with their long necks they would rake vegetation from their surroundings for perhaps 16-20 hours a day. They can't have had much time for sleep.

"They were extraordinary animals," says NHM palaeobiologist Paul Barrett. "Colleagues have called them 'ecosystem engineers' because their behaviour would have had a major effect on the physical appearance of an environment, not just in eating the vegetation but in clearing it out.

"Think also about the effects they would have had in terms of the geochemistry from their defecation as they moved through the landscape.

"The runoff would be influencing the amount of nutrients entering rivers. The seeds they dispersed were potentially controlling the distribution and germination of a number of different types of plants."

Amazing

discovery

The history of science is littered with rivalries but the animosity that drove Othniel Charles Marsh and Edward Drinker Cope was something else.

These two individuals went to war in the 1870s to prove their paleontological prowess and intellectual superiority. The collectors turned Wyoming and adjoining states into a fossil battlefield as they raced to unearth and describe new dinosaurs.

To try to out-do each other, they employed the most underhand of tactics, including bribery and sabotage. Every scientific publication by one was immediately trashed by the other. Marsh's and Cope's obsession nearly bankrupted them both.

But in this manic pursuit of one-upmanship, they pushed the science forward, introducing to the world more than 130 new species of dinosaur. One of their big reveals was Stegosaurus, the rhino-sized animal that's instantly recognisable to all thanks to the row of sharp bony plates along its spine. Visitors to London's can see a particularly fine example.

This specimen, nicknamed "Sophie", is the most complete in the world. It was discovered in the Morrison Formation in 2003, just down the road from the Mission Jurassic dig site.

Sophie's story is a good illustration of what will happen next to the creatures currently being pulled from the Badlands rock.

Their bones will go to the TCMI lab where they'll be relieved of their plaster jackets, cleaned of any extraneous sediment and then subjected to a battery of tests. Whereas early palaeontologists might have done little more than describe the beasts and try to reassemble their bones in a best-fit posture, today's researchers use an ever-more sophisticated set of tools to bring the animals back to life - in the digital sense.

Bones loaded on to the back of a truck

Bones loaded on to the back of a truck

The fossils are examined to see where ligaments and tendons attached. Computer models will then add muscle and skin; feathers even, if there's evidence they were present.

This is where those preserved trackways are insightful because all this information can be used to reconstruct a dinosaur's movement, and that will help with the broader picture of how the animal negotiated its environment: what kind of distances could it cover? How much energy would that mobility expend?

βWe now have a T. rex you can download and build yourself β

One of the newer techniques involves fine X-ray investigation of the fossils to look at their chemical make-up. "This can tell you how fast the animal was growing and whether it experienced some hard periods in its life because that growth was stunted," says TCMI's Jennifer AnnΓ©.

"If you're really, really fortunate, you might find something we call medullary bone, which we think means the dinosaur was getting ready to lay eggs. You can also see if they had an injury and how well it healed; and sometimes you can see evidence of disease, maybe an infection or arthritis." Sophie displayed no obvious defects on her bones, nothing that points to disease or predation. The suspicion is she may simply have been unlucky and died from starvation during one bad season. Today, the technology that's having a major impact on palaeontology is 3D printing. This is revolutionising scientists' ability to study and share specimens.

"It's so easy to do scaling," says Anne Schulp, another vertebrate palaeontologist from the Naturalis Biodiversity Center. "If you have a younger, smaller Triceratops with some bones missing, you simply go to a larger animal, dial down the size of its bones and click print. And it's great for education. We now have a T. rex that you can download and build yourself."

The bones of the Mission Jurassic sauropods are somewhat jumbled up; quite a few are missing. It's going to require therefore a bit of interpretation and printing to reconstruct the animals.

has first claim to keep and display the giants, but both Naturalis and the Natural History Museum could easily mount their own 3D copies back in Europe.

Sundance

"Do you want to see the Sundance? It's pretty special," says Mark Graham, an NHM fossil preparator. "If you do, we've really got to go now before it gets too hot."

The Sundance is the "big bonus" in the Mission Jurassic square mile. It's an older sequence of rocks that sits below the Morrison and records a time when Wyoming was covered by a shallow inland sea. Thus its fossils are likely to be of marine creatures.

We head off in the SUV along a rutted track to a nearby ridge. To go back in time in the Jurassic we must descend, and that means clambering down the steepest of inclines.

Almost immediately the heat hits us. The south-facing slope has been soaking up the Sun and even though it's only 11 in the morning, we feel now as though we're being roasted from below and above.

After a few minutes, we break our downward slide and catch breath on a level platform of rock. Tim Ewin, an invertebrate specialist with the NHM, walks up and drops something shocking into our hands. A pile of bullets.

It can't be! And fortunately that instant fear quickly gives way to relief. The dark "ammunition" we're holding is actually belemnites - the fossil remains of squid-like creatures that swam in great abundance in the Sundance Sea 160-170 million years ago.

How abundant? We look around and realise the ground is littered with them. They're everywhere. And it's not just belemnites. We're directed also to the distinctive shape of "devil's toenails", or Gryphaea to use their scientific name. These were ancient oysters whose fossilised shells resemble satanic nail clippings.

We carry on down the slope to where Mark has removed a tarpaulin from a tangled mass of fossil bones. It's a "sea dragon", also referred to as an ichthyosaur, a hugely successful marine reptile that looked a bit like a large dolphin. It would have dined on the aforementioned belemnites.

The NHM man can't hide his irritation, though. This specimen has been badly damaged at some point by fossil thieves who clearly tried to remove the bones in a hurry and made a dreadful hash of it. "It's one of the worst examples of privateering you'll see," he says.

Nonetheless, this incomplete specimen may yet hold valuable science. It will be extracted (properly) and examined for clues as to how it lived and died.

Ichthyosaurs gave birth to live young. If this was a pregnant female, her progeny may have been fossilised with her.

But as fascinating as the sea dragon is, it's not the reason we've suffered the drop into this oppressive heat trap. That's another 20-30m further on, and when we arrive at the next ledge we find Richard Herrington, the NHM's head of Earth sciences, already gently prising apart delicate sheets of rock with a bayonet.

Mark puts a grey slab at our feet and opens his palms. As he does so, the slab splays, its individual layers separating like the paper pages in a book. These lithographic limestone and mudstone layers represent the sediments that settled at the bottom of an ancient, hyper-saline lagoon. Any animals that swam into, or fell into, this shallow pool probably suffocated in its quiet, super-salty, oxygen-poor waters.

It's a setting however that makes for truly remarkable preservation and the entire Mission Jurassic consortium is especially excited about the potential of these particular fossil beds.

Already insects and plants are turning up in these paper-thin layers. Fish too. "It's amazing. You can see every small bone in life position; their scales and fins as well," enthuses Tim Ewin.

The scientists say the deposits remind them of the famous Solnhofen limestones from southern Germany which have yielded some of the most spectacular of all Late Jurassic fossils, including one of palaeontology's true "rock stars" - Archaeopteryx, the winged creature that essentially proved the evolutionary link between dinosaurs and birds.

Could these Wyoming sediments hold something similar?

For the NHM and Naturalis, there is now great desire to join the Children's Museum in making a long-term commitment to this square mile of Badlands. The possibilities seem overwhelming.

The London institution is talking of opening its own dedicated quarry where students could be brought over for training, even museum donors to see where their money is going.

"It would be an important statement from us that we still do expeditions; we still do 'live' science," says Richard Herrington. "We want to say loudly that we're collecting new stuff, not just working on old material. We're modern and we're addressing the latest research questions."

Back up at one of the quarries, Phil Manning is turning a large crystal lump in his hands. When bone has been in the ground for a long time, its calcium is liberated into the surrounding sediments to form gypsum. Finding chunks of the mineral is a sign that more dinosaur remains are close.

But at this precise moment, the Manchester man is very excited because his team has just had a eureka moment. Looking at the melange of sauropod fossils in front of them, itβs clear now how the different pieces fit together to make a massive pelvis.

βDo you know, fear was what I felt when I first walked on to this site because I realised we were getting into something really huge. But it's something we just have to do because the material is so wonderful.

"Every single palaeontologist from every museum and every university who comes to work here will dream about this place at night.β

Author: Jonathan Amos

Online Producer: James Percy

Field Producer: Alison Francis

Graphics: Gerry Fletcher

3D animations: George Spencer, Mark Edwards, Terry Saunders

Videos: Julie Ritson, Dave Rust, Phil Manning, Ultimaker

Editor: Kathryn Westcott

Images: Jonathan Amos, Natural History Museum, The Children's Museum of Indianapolis, Alamy, Bob Nicholls / Paleocreations 2014

More Long Reads

Mission to separate conjoined twins

To the moon and beyond

Seeds of life

Publication date: 15 August 2019