Wir sind Deutschbriten

How we made a life in Germany

By Kevin Connolly

When you are a migrant, timing is everything.

Sometimes that’s because you have to judge the moment when the time has come to leave your home, if you’re driven by war and disease or famine and poverty.

Sometimes it’s because there are opportunities in the country to which you want to move - a labour shortage, perhaps, or a relaxation of visa rules.

When we think about movements of population, we tend to mean from poorer countries to richer ones in search of a better life.

Things are more complex if it’s between countries with roughly similar levels of prosperity.

The British and the Germans, for example, have been settling in each other’s countries in small but significant numbers for many years. The precise numbers have always depended on the prevailing historical circumstances. Joint membership of the European Union since 1973 has made it easier to move for work, but the UK also left armies of occupation in Germany after both world wars.

For nearly 200 years, Britain has had a royal family drawn from German nobility. All that shared history created plenty of shared roots as courtiers flitted between the two capitals, soldiers settled down with German wives, and workers took advantage of the EU’s freedom of movement to build new lives.

History created the framework and every settler chose the time that was right for them.

Ruth

Timing is important in the life of Ruth Barry, a young businesswoman who migrated from Scotland to Germany by way of England and France.

Ruth is a baker and professional baking relies on meticulous control of time and temperature allied to precise measurement of ingredients and repetition of method.

Ruth’s business is the Black Isle Bakery in the smart Mitte district of Berlin.

The calligraphy on the shop front is elegant - the decor inside spare and minimalist. The walls are white, punctuated with quotes evoking the Black Isle itself, Ruth’s Scottish home to the north of Inverness.

But that elegance and minimalism is not the whole story.

“It’s a really hard life and people don’t get to see that,” she says. “People think it must be nice that I get to do my hobby, but they don’t see me lugging 25kg sacks of flour around when I’ve been here since 05:45, and I haven’t sat down and I haven’t eaten lunch and I’ve also been serving people.”

Her fierce work ethic and attention to detail clearly helps to provide the fuel of energy and determination you need to succeed in a new country.

But her decision to start a new life has come at a cost: “If I was in Berlin and I had a salary and I felt some kind of freedom, I think Berlin would be a wonderful place to be. I think you can have a quality of life here that was not available to me in London.”

Most migrants, of course, look for jobs when they exchange one country for another. Only a small minority do what Ruth has done and create a business for themselves out of nothing.

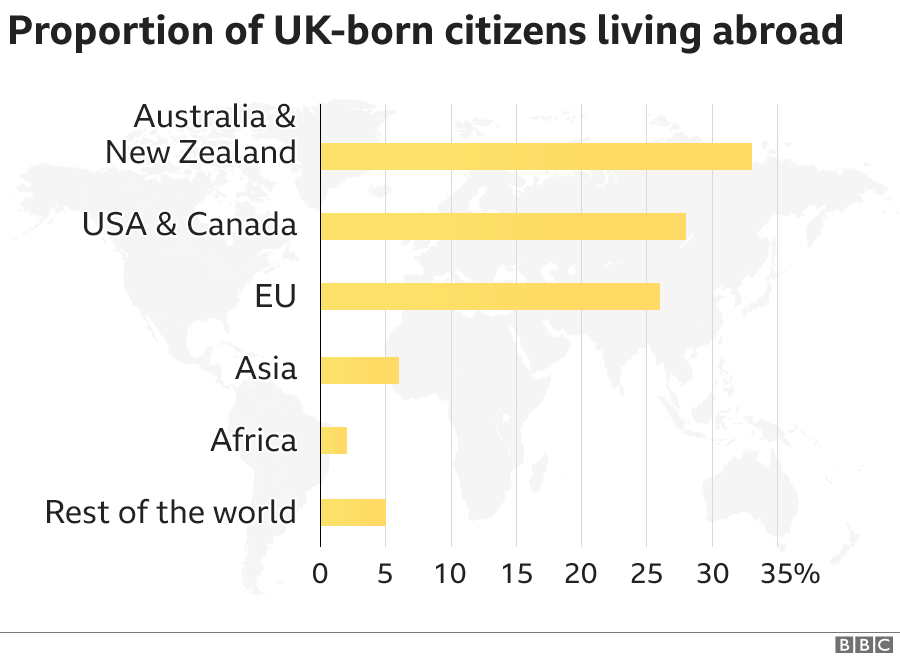

The British abroad

- UK citizens tend to emigrate to English-speaking countries

- In 2016, 34% of the UK population said they could speak a foreign language, the lowest percentage in Europe - the EU average was 64.6%

- Of the UK citizens who have migrated to the EU - 37% live in Spain, 19% in France, 6% in Ireland

Sources: ;

Baking can be hard work. Baking in a foreign country can be even harder. And baking in a country where commercial regulations and banking rules weren’t written to help the entrepreneur is probably the hardest work of all.

Her experiences provide a checklist of the relative advantages of operating a start-up business in London and Berlin.

The main difficulty in London is the price of property - not just renting a shop or working kitchen but paying for somewhere to live.

Ruth’s sense is that property prices in Berlin are rising quickly - to the resentment of some locals watching an influx of migrants - but they’re still far below London levels, and so less of a drain on a start-up budget.

But some of the barriers to business are more subtle. Ruth has found the German banking system to be expensive and cumbersome compared with the UK’s.

On top of that, she says, there are challenging cultural attitudes to entrepreneurship.

Germany, of course, is an economic powerhouse, a strong presence in the global export trade in cars, machine tools and all sorts of precision engineering.

But that doesn’t necessarily trickle down, in Ruth’s experience, into a cultural sympathy for the businesswoman looking to get a new business off the ground.

In Berlin, she says, there’s no great history of small-scale, start-up capitalism.

“There’s a very strong focus here on craft,” she says. “For two years, you go and learn how to be a baker and at the end of that you have your certificate that says ‘Bäckermeister’, so that doesn’t leave much space for entrepreneurialism.”

And that feeds through into a kind of consumer conservatism too, Ruth reckons.

Many Germans, it turns out, have very specific and very conventional expectations of what you should find in a bakery, and the purpose of opening new bakeries in their view is not to widen the repertoire of goods on offer, but to expand the number of places where you can buy the same narrow range of delicacies.

As Ruth explains: “When they come in and they see that we don’t have the dark heavy rye bread, or the little bread rolls, or torten, I think they’re disappointed.”

Ruth’s approach though is prospering. One magazine described her millionaire’s shortbread as being like “the best Twix on the planet”, and her strictly seasonal approach to ingredients is a little signal to customers that the focus is on quality rather than familiarity.

We visited in autumn when the season of tomatoes was giving way to the season of pumpkins - a time for even the most conservative customer to try something new.

Germany

- 15% of the population are immigrants

- Germany is a major destination for recent asylum seekers in Europe

- Germany received more than twice as many asylum applications as the US in 2016

- A low birth rate has led the government to encourage immigration

Source:

Migrants of course have to learn lessons from their new home.

For Ruth, that means thinking about producing “empire biscuits” - something that middle-aged Germans in particular consider to be a British delicacy but which the British themselves tend never to have heard of.

The second lesson is simple - sometimes you have to go where the market takes you.

Ruth, for example, has discovered that German people love scones.

“Honestly,” she says, “I am just going to have to start making them because I get asked about 17 times a week.”

Some of the data in this article is drawn from Â鶹ԼÅÄ Briefing, a mini-series of downloadable in-depth guides to the big issues in the news, with input from academics, researchers and journalists. It is the Â鶹ԼÅÄ's response to audiences demanding better explanation of the facts behind the headlines.

Quick Â鶹ԼÅÄ Briefing links:

Sheila and Stephanie

Sheila Barnes settled not far from Hanover because she fell in love here as a young woman.

She’s now lived in the area for 40 years. For 36 of those she has been working in logistics for the quintessentially German firm, Mercedes-Benz.

Sheila is entirely integrated into German life and speaks the language fluently.

Ask Sheila if the UK now feels like a foreign country and she replies with the curious German hybrid word ‘jein’ - a combination of yes and no.

At a more practical level Sheila can see the benefits of having settled in Germany - particularly in times of sickness.

After a long and complex period of ill-health, Sheila sums it up: “Healthcare is good here. With my medical insurance I’ve had treatments I couldn’t get in Britain. There are good things about life in Germany.”

The dream of one day living in England hasn’t entirely faded, but there are financial issues to weigh alongside the emotional.

“For me that will always be home,” she says of her grandmother’s home near Deal in Kent, “If it wasn’t so flipping expensive, I’d definitely think about moving back, but I’d have to win a million.”

That same combination of personal circumstances and financial barriers probably shapes the lives of most immigrants, most of the time. But there's another factor that Sheila has to bear in mind - the views of her father, even though he’s long since died and been cremated.

“It would feel wrong to give up my British citizenship,” she says. “My father would have a sandstorm in his little urn.”

The same issues of belonging and identity are perhaps even more complicated for Stephanie Thomas, born to a British soldier and the German woman with whom he fell in love.

Stephanie and her older sister stayed in Germany with their German grandparents when their parents moved back to England.

Her grandparents - essentially out of kindness - stopped the two girls from speaking English to each other, to speed up the rate at which they learned German. It worked, too.

Stephanie sums up her sense of identity like this: “I believe that my brain is English and I learned to be German. I like the English me more than the German me.”

Stephanie, who’s now mum to two German-speaking daughters, provides a reminder of how complex the choices migrants face often are.

As a teenager, she thought of following in the footsteps of her soldier father and joining the army - except in her case it was the German army. She was talked out of it by her grandfather who had been forced to join the Hitler Youth Movement.

There’s a note of wistfulness in part of Stephanie’s story just as there was in Sheila’s - the thought that, for all her German-ness, England is a kind of ultimate home, even though it’s never really been home.

“I hope I end up living in England,” she says. “I keep thinking about it. I can’t put the thought aside. Then kids come along and you have to re-organise your own life.”

No-one knows yet what the final consequences of Brexit might be, but Stephanie is thinking of applying for a British passport to make it easier to travel to England and back to visit family. While Germany and the UK have both been in the European Union that hasn’t been necessary.

EU membership and the freedom of movement it offers means it’s sometimes hard to be sure how many citizens of one member state live - or have lived - in another.

But that community of former British soldiers and their children who made the decision to stay in Germany illustrates the point that migratory flows are made up of thousands - and sometimes millions - of individual decisions, shaped by huge historical events.

The end of WW2 and the creation of the British Army of the Rhine were two such events. In the uncertain world of Brexit the question is, what pressures will shape the movement of people between Britain and Germany (and the wider world) in the future?

Global movement

Migration is one of the hardest subjects to analyse, because it’s both universal and intensely personal.

Many migrants move as refugees because war, famine and disaster drive them from their homes. Others are motivated by the search for a better life.

Movement between countries with roughly similar levels of wealth and development are even harder to analyse.

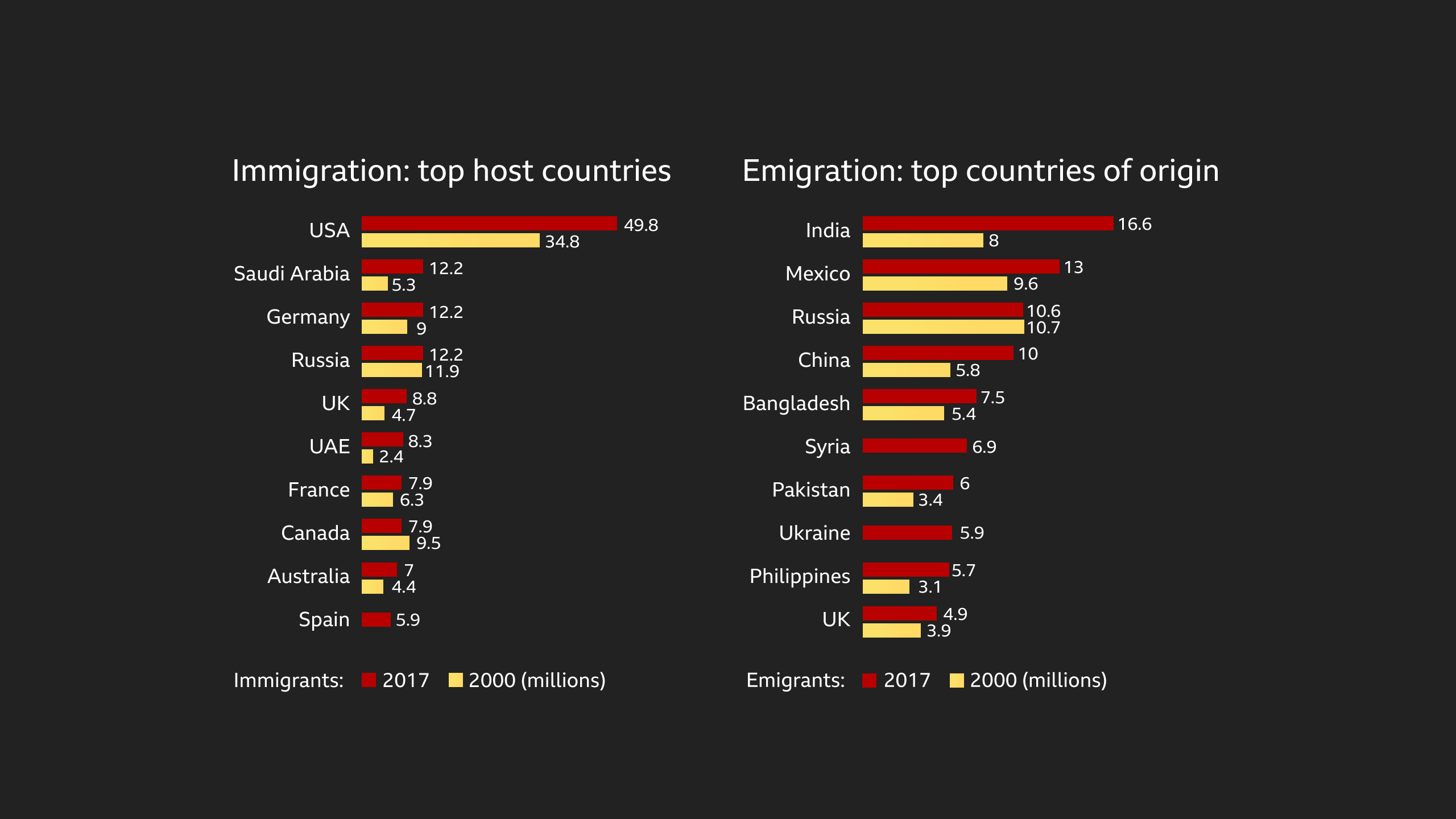

Top 10 countries

- The UK is among the world’s leading countries, both as a destination for immigration and as a source of emigration

- In 2017 the top 10 host countries accounted for half the 258 million global migrants

- The top 10 source countries account for a third of all migrants

Source:

Sometimes migration is a matter of fashion - lots of Americans flooded to the Paris of the 1920s for example.

In the early 2000s, something similar happened on a smaller scale with British citizens who had an affinity with Germany, often because they’d studied the language at university.

Once again you have a sense of how migration is shaped by a combination of large global factors and small personal decisions.

In many parts of the EU, the precise scale of those trends has become hard to measure because movement between member states - in the theology of European integration - wasn’t seen as migration in the traditional sense. That is the essence of the policy of Freedom of Movement.

But if key chapters in history, like the shared Hanoverian monarchy and the British military presence, shaped migratory flows in the past, then it’s reasonable to assume that Brexit will provide another, similar moment of change.

The official estimate of the number of UK citizens living in Germany is a pleasingly precise 116,470. There is even a symmetry in the way that the number of Germans living in the UK roughly matches the number of British migrants who’ve travelled in the opposite direction - just over 100,000 in each case.

The actual number may be slightly higher or lower because it’s not clear exactly how individuals with dual nationality are counted. Germany allows people to hold joint citizenship with another country as long as it’s an EU member state. That’s included the UK until now but may not after Brexit.

For that reason the number of British applications for dual nationality or naturalisation has jumped as Brexit looms - from 622 in 2015 to 7,493 in 2017, and what’s anticipated to be a higher number for the next 12-month period to be measured.

Source: Destatis (Federal Statistical Office of Germany)

The effect of Brexit so far has been to create a mood of anxiety among British expatriates in other EU member states.

There is uncertainty over how access to state healthcare will be managed in the future and over long-term issues such as arrangements for paying pensions in one country, when they are based on National Insurance contributions in another.

Some will have to consider applying for a passport from another member state to protect their status as EU citizens, even if that means giving up British nationality, as it probably will in Germany.

Similar factors weigh on the three million or more EU citizens who’ve made their home in the UK.

In a field notoriously hard to measure and predict, it seems safe to say that migration between countries like Germany and the UK will continue, even if the legal and political framework around migration changes.

That’s because a small minority of people have always been ready to leave their homes and move between countries, and the reasons are often subtle and not likely to be swayed by the prevailing political climate. Often people are driven by a sense of adventure, by job opportunities created through language skills or simply because they fall in love.

The question for our age is what pressures will help to shape the movement of people between Britain and Germany and the wider world in the years to come.

Some of the data in this article is drawn from Â鶹ԼÅÄ Briefing, a mini-series of downloadable in-depth guides to the big issues in the news, with input from academics, researchers and journalists. It is the Â鶹ԼÅÄ's response to audiences demanding better explanation of the facts behind the headlines.

- (PDF)

Credits

Author: Kevin Connolly

Producer: Michael Innes

Photography (Ruth, Sheila and Stephanie): Jessica Jungbauer

Archive images: Getty Images, Alamy

Additional archive photos courtesy of exhibitions “The British in Westphalia” and “The British in North Rhine-Westphalia” - curated by Dr Bettina Blum and copyright Gisela Meyer, Jocelyn Matthews-Hoyle, Stadt- und Kreisarchiv Paderborn / Philip Andrews

Graphics: Gerry Fletcher

Online production: Paul Kerley

Editor: Kathryn Westcott