We've updated our Privacy and Cookies Policy

We've made some important changes to our Privacy and Cookies Policy and we want you to know what this means for you and your data.

Make or break for Ireland finances

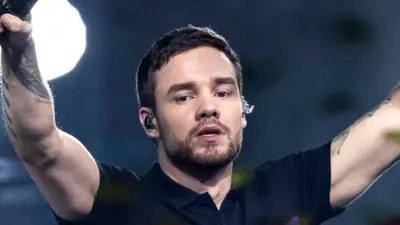

ΒιΆΉΤΌΕΔ business editor Robert Peston on a new bank bail-out in Ireland

It is make or break for Ireland's public finances.

The Irish Finance Minister, Brian Lenihan, has announced what he hopes will be a comprehensive and final rescue scheme for Ireland's banks, whose reckless lending has mortgaged the entire Irish economy.

The most reckless of the lenders, Anglo Irish, is to receive a further β¬6.4bn (Β£5.5bn) of state aid. An additional β¬2.7bn (Β£2.3bn) goes into Irish Nationwide.

And the National Pension Reserve Fund is to inject up to β¬7.2bn (Β£6.2bn) into Ireland's second biggest bank, Allied Irish Banks - which will in effect be nationalised, with the state fund likely to hold more than 80% of its shares.

The cost of the rescue to Irish taxpayers, including earlier measures, lifts the deficit in Ireland's pubic finances from a painful 12% of GDP to a staggering 32%.

Anglo Irish on its own is receiving just under β¬30bn (Β£25bn) of equity investment from the Irish taxpayer.

For what it's worth, the Irish taxpayer could get up to β¬2.4bn (Β£2.1bn) from subordinated debt holders in Anglo: Mr Lenihan has said that since these investors provided capital that was supposed to be at risk, they should shoulder some of the pain. That said, converting their debt into equity will not be a speedy process.

Mr Lenihan has also reaffirmed what he said to me on Friday that he believes it would be lethal for the Irish economy to force losses on any other creditors of Ireland's banks, even if they are sophisticated banks and professional investors who should have known better than to finance Irish banks' lethal lending spree.

If you add together all the capital provided to Ireland's banks by various arms of the state, taxpayer support to those banks in the form of capital injections is around 30% of GDP.

That would compare with around 6% of GDP in the UK for the equity injected into Royal Bank of Scotland, Lloyds and Northern Rock.

In Ireland, some would also include in the cost of the rescue the further 25% of GDP that is being provided to the banks in form of state-backed bonds, as payment for the toxic loans they've transferred to the banking rescue fund, the National Asset Management Agency.

In other words, more than half of Irish GDP has been devoted to keeping its banks afloat.

That said, NAMA is acquiring these loans at a substantial discount to face value - and NAMA's chairman, Frank Daly, told me that over 10 years he would expect NAMA to make a profit when it finally secures whatever repayments it can from the property developers and speculators who borrowed colossal sums from the likes of Anglo Irish and Allied Irish.

And what a discount! NAMA is paying just 33 cents in the euro to Anglo Irish for the remaining tranche of β¬19bn (Β£16bn) in dodgy loans it is taking from the bank. Which implies that the quality of these loans is hideously poor.

The big question for the banks and overseas investors which have lent more than a trillion euros to Ireland's banks, businesses, households and the government is whether the banks' losses will now stabilise.

Mr Lenihan is attempting to reassure them that cataclysm can be avoided by taking further steps in December's budget to cut public spending and thus the deficit. He has reaffirmed his commitment to reduce the deficit to 3% of GDP by 2014.

He feels this is necessary because of the speed with which Ireland's public-sector debt has risen from one of the lowest in the eurozone as a percentage of GDP to 98.6 of GDP (or 70.4% deducting cash and investments). Mr Lenihan says his objective is to stabilise the national debt in relation to GDP by 2012/13.

But some investors will be concerned that with the Irish economy showing a small contraction in the second quarter of the year - following the acutely painful recession of the previous two years when Irish output shrank by around 14% - Ireland is on the brink of a vicious cycle of a public spending squeeze, which undermines economic activity, generates further losses for banks, reduces tax revenues and pushes up the national debt even further.

So it's just as well, perhaps, that the Irish government has already borrowed enough from investors this year to finance itself until the middle of next year.

The finance minister hopes (and probably prays) that by the time the government has to borrow again, early in the new year, the state's creditors will be confident that Ireland banks and the nation's finances are on the mend.

You can keep up with the latest from business editor Robert Peston by visiting his blog on the ΒιΆΉΤΌΕΔ News website.

Top Stories

More to explore

Most read

Content is not available