Image: Delia Derbyshire composes using multiple reel-to-reel tape machines in June 1965.

The Βι¶ΉΤΌΕΔ Radiophonic Workshop provided a base for a series of exceptional composers and sound designers but none of them generated quite the same level of interest and fascination as Delia Derbyshire.

Her life has been dramatised on stage, screen and radio but although she remains most famous for her arrangement of the Doctor Who theme tune there was far more to her creative activity, both at the Βι¶ΉΤΌΕΔ and beyond.

Delia Derbyshire was born in Coventry in 1937 and grew up in what she described as an upper working class family. At school, she demonstrated an affinity for the potential of everyday objects to create music and distinctive sounds from her childhood would haunt her later work.

There are echoes of the air raid sirens during the Blitz while the clogs of factory workers bustling along the cobbled streets of Preston (where she was evacuated during the Second World War) are suggested in the 'clip clop' rhythms of pieces like Pot au Feu (1968).

She thrived in Music and Mathematics, falling in love with the work of composers like Beethoven, Bach and Mozart, and won a scholarship to Cambridge.

Electronic music was not yet on the curriculum, however, and her interest in that field was furthered by a visit to the Brussels World's Fair in 1958 where she experienced Edgard Varèse's Poème Électronique installed in Le Corbusier's pavilion. This was a groundbreaking fusion of electronic music, architecture and visual art and would have a deep influence on Derbyshire's future practice.

Having been rejected by Decca, where she was told that women were not employed in their studios, she joined the Βι¶ΉΤΌΕΔ in 1960 as a trainee assistant studio manager. In 1962 she requested a transfer to the Βι¶ΉΤΌΕΔ Radiophonic Workshop and she would remain there until 1973.

Derbyshire's early assignments at the Workshop included music for the docu-fiction Time On Our Hands (1962) and short title themes for factual shows, like the witty opening cue for Know Your Car (1963), but it was across 1963 and 1964 that she created some of her most significant and influential works.

Her arrangement of the Doctor Who theme would contribute massively to the growing public awareness and appreciation of electronic music in Britain (elements of Derbyshire's version can still be heard in Segun Akinola's arrangement of the theme for the programme's 2018 series). That interest is exemplified by a 1964 edition of the radio show Information Please in which Derbyshire explained the mysteries of the Doctor Who theme and electronic music to a bemused Franklin Engelmann:

If the Doctor Who theme is still the best known 'Delian' piece, Derbyshire's collaboration with the dramatist Barry Bermange on the four Inventions for Radio, first broadcast in 1964 and 1965, would enable her to develop her ideas on a much larger canvas. As her close friend and Workshop colleague Brian Hodgson put it, these extended works showed Derbyshire at 'her elegant best'.

In the following extract from a short Βι¶ΉΤΌΕΔ training film about the Radiophonic Workshop, Derbyshire discusses briefly her work on the Inventions with an extract from The Dreams (1964), the first in the series:

These four works formed a distinctive genre of radio feature, blending electronic music and soundscapes with a poetic collage of interviews with members of the public. The Inventions were remarkable both for their technical achievement and the fact that they privileged the voices of everyday people and their thoughts on weighty philosophical subjects, such as the possibility of life after death and the experience of ageing, at a time when the portrayal of British working class communities and individuals was limited and often clichΓ©d.

The Βι¶ΉΤΌΕΔ received complaints from some listeners about the 'harsh' or 'uneducated' accents of some of the speakers and there was frustration that these 'inane… nonentities' were allowed to express their thoughts about such profound subjects on national radio. The second of the Inventions, Amor Dei (1964), was a case in point with the interviewees addressing the existence of God:

Derbyshire worked with Bermange on the editing of the voices and created the evocative music for each of the Inventions. The Dreams drew heavily on the manipulated resonances of recordings of a metal lampshade being struck, one of Derbyshire's favourite sound sources, and the entire score of Amor Dei, full of expansive ethereal chords, was derived from the recording of a boy chorister.

Although he does not acknowledge Derbyshire by name and downplays her role somewhat, Bermange's admiration for her work is audible in the following interview with H.A.L Craig from December 1964:

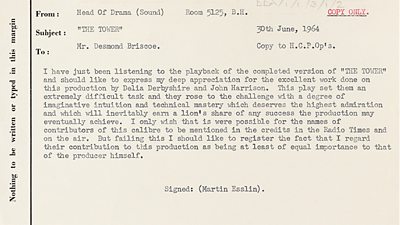

Derbyshire's reputation was burgeoning. Despite the Βι¶ΉΤΌΕΔ policy, in the 1960s, of not giving individual credits to Workshop staff, it is clear that she was held in high regard by a number of senior figures at the Βι¶ΉΤΌΕΔ. There's a good example of that respect in a 1964 memo from the Head of Radio Drama, Martin Esslin, in which he expresses regret that Derbyshire and her colleague John Harrison could not be credited for their work on The Tower (1964):

One of Derbyshire's finest works was Blue Veils and Golden Sands, created originally for a 1968 edition of The World About Us, on the Tuareg people journeying across the Sahara. For this piece, Derbyshire made use of her beloved metal lampshade and her own voice, recorded and re-pitched to create the counter-melody for the camels making their way through the heat haze of the desert.

Her personal archive at the University of Manchester includes a tape that reveals Derbyshire's creative process, as variously pitched snippets of her voice are augmented, spliced together and filtered into the final piece:

By now, Derbyshire was being credited for her Βι¶ΉΤΌΕΔ work and had established an impressive freelance profile. She collaborated with major figures in Britain's arts scene, ranging from Peter Hall and the Royal Shakespeare Company to Yoko Ono and Ted Hughes as well as a rewarding extended collaboration in the 1970s with the pioneering artists Elsa Stansfield and Madelon Hooykaas.

She worked in different styles and moods: layering squelching dance beats for Schools Radio or shimmering ambient soundscapes across documentaries as well as playful reinventions of nursery rhymes and aggressive, mashed-up industrial rhythms. If she was the first composer at the Βι¶ΉΤΌΕΔ to show that 'radiophonics' could be beautiful, she was unafraid to be unsettling and menacing.

Yet, by 1973, Derbyshire herself was feeling unsettled at the Βι¶ΉΤΌΕΔ and what she perceived as an increasingly commercial environment that was no longer sympathetic to her creative principles. She left the Radiophonic Workshop and relocated to northeast Cumbria for several years before returning to London in 1978 and then settling in Northampton with her partner, Clive Blackburn.

Her post-Βι¶ΉΤΌΕΔ years have often been characterised as a tragic long decline into poor health and complete withdrawal from music but the truth is more complicated than that. She was still taking on the occasional freelance project into the 1980s and, according to Clive Blackburn, worked on music in private but her public output reduced to the point where it seemed to many that she had ceased to create.

When Derbyshire died in 2001, she had started to collaborate on new music with Sonic Boom as the available technology had begun to catch up with her thinking. She influenced and is admired by bands and artists as diverse as Pink Floyd, Orbital, Portishead, the Kronos Quartet and Cosey Fanni Tutti. Concerts and new works are increasingly commissioned in her honour, not least through the educational charity Delia Derbyshire Day.

Her creative spirit and refusal to be held back by barriers around gender and class is an inspiring example of artistic adventure and integrity.

Delia introduced new and previously unheard voices - quite literally - to the Βι¶ΉΤΌΕΔ and her work continues to encourage new generations to find their own creative voice.

Written by Dr David Butler, University of Manchester with thanks to Mark Ayres, Clive Blackburn and Caro Churchill.

Radiophonic links

-

Women of the Workshop

The women who shaped the pioneering sound of the Βι¶ΉΤΌΕΔ Radiophonic Workshop. -

Charity organising events about Delia Derbyshire, centred around her Archive held at John Rylands Library, Manchester.

Charity organising events about Delia Derbyshire, centred around her Archive held at John Rylands Library, Manchester.