βImpartialityβ is always changing; what is seen to set its limits alters as circumstances throw up new views of things, yet the sincere attempt to be fair and open-minded is urgent, ongoing and vital. Arguments that it is not βperfectβ or at times a defence for entrenched power have a point. However there is no alternative to the attempt except partisan propaganda. While impartiality has a history before the ΒιΆΉΤΌΕΔ makes it its own, in the hands of the ΒιΆΉΤΌΕΔ it became a revolutionary new practice.

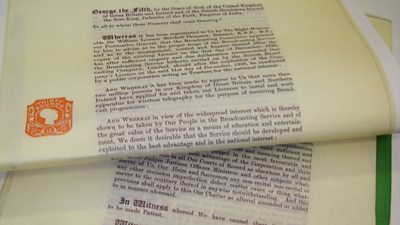

What was completely new about the ΒιΆΉΤΌΕΔ was that it took the form of a commercial company β as the ΒιΆΉΤΌΕΔ was originally, before it was reinvented as a corporation β yet put βthe public interestβ not βprofitβ, βexcellenceβ not βcheapestβ, and βfor everyoneβ not βfor someβ as the goal. This was radical. It was also unique internationally.

John Reith, the first, awkward, narrow-minded and visionary director general explained nearly 40 years later why that was vital:

Impartiality in founding DNA - itβs the structure stupid!

The at the dawn of a spectacular new way of communicating because of a panicked anxiety that the final tranche of enfranchised voters might vote, not according to their material interests or ideals, but because the new means of broadcasting would be so invasive and so persuasive. There were concerns that:

- public views could be bought behind their backs by βbig businessβ for commercial gain.

- public views would be distorted by foreign (or domestic) ideologues βinfluenced by propaganda.

- that because of the distrusted role of the press during World War One, the public would distrust government and the media.

- there was a need to avoid the potential divisiveness of the new technology of broadcasting β which was exactly how the Germans and the Russians used it to divide and exclude later in the 1930s.

The aim was to create a single national conversation. Not one that everyone agreed with, rather that everyone could have some foundation for discussing things that would shape their lives more carefully. Impartiality was at first seen narrowly as a defence against political pressure from political parties - although the ΒιΆΉΤΌΕΔ accommodated that at times and resisted that at others. The ΒιΆΉΤΌΕΔ did not βknowβ what impartiality might mean until it tried, inevitably imperfectly, to put it into practice. In this way, impartiality is always having to be reconstructed.

The General Strike

The ΒιΆΉΤΌΕΔβs commitment to independent impartiality was tested acutely when the General Strike broke out. The ΒιΆΉΤΌΕΔ was in a delicate political moment of transition from company to corporation and the nation was in chaos. The strike, which lasted for nine days between 4 and 12 May in 1926, was called by the Trades Union Congress in an unsuccessful attempt to stop wage reductions for coal miners. It was an intensely febrile moment and pitted middle-class volunteers and the government against working-class strikers. So soon after the end of World War One it also pitted people who had served together against each other. The ΒιΆΉΤΌΕΔ had to invent what βimpartialityβ might mean on the hoof: it meant giving the public accurate information they needed and attempting, in a very polarised situation, to give the competing sides - the government and the unions - some kind of a fair hearing.

World War Two 1939-45

George Orwell, wrote in the Labour Party newspaper Tribune in 1944 that βI heard it on the wireless,β is now almost equivalent to βI know it must be trueβ. By the time World War Two broke out in 1939 the ΒιΆΉΤΌΕΔ was central to nearly every home in the country. The 'home front', the struggle for civilian domestic morale came to be seen as vital. What role could βimpartialityβ have in a war for national survival? The ΒιΆΉΤΌΕΔ was part of the war effort and it was under new government controls but it was not taken over by the government despite pre-war criticisms, when the ΒιΆΉΤΌΕΔ was seen to have failed by giving airtime to anti-appeasers from both right and left, the pre-war version of impartiality. Presenting both sides of political arguments came under pressure at a time of existential threat from war. This was domestically complex but also gave the ΒιΆΉΤΌΕΔ a wider scope of independent action.

However, the ΒιΆΉΤΌΕΔ discovered that in order to broadcast into a nation under attack, βimpartialityβ was a pragmatic policy not just a moral one. People would only listen if they thought it was worthwhile, that trust had to be grown and maintained by accuracy; audiences trusted reporting when it was successfully tested against their own experience, and that βimpartialityβ was also an issue of speed and tone. The ΒιΆΉΤΌΕΔ had to be first and fast and so there was a huge increase in reporting capacity. It also had to understand the audience better. The catastrophic defeats in the first two years of the war could not be hidden. So, by reporting them the ΒιΆΉΤΌΕΔ enhanced its impartial legitimacy, while still able to provide cheer with stories like the βlittle boatsβ bringing back troops from Dunkirk.

Leonard Miall joined the hastily assembled ΒιΆΉΤΌΕΔ European Services which broadcast in French, German and Italian into Europe. Other languages soon followed.

The ΒιΆΉΤΌΕΔβs broadcasts into Europe had a different tone. But even on this front line in the war of words between Britain and the Axis powers, the ΒιΆΉΤΌΕΔ was especially keen to promote editorial values of βtruthfulnessβ and accuracy. Trust of foreign listeners, risking their lives to listen in occupied Europe would only be earned β and the propaganda war won β if British failures were reported as well as successes. Impartiality in itself, when it faced bleak realism, had propaganda value because it spoke volumes about freedom.

Radio announcer and Assistant Controller of the European Services Harman Grisewood explains how the ΒιΆΉΤΌΕΔ navigated its relationship with the government in wartime.

Chief International Correspondent Lyse Doucet reacts as a contemporary journalist to the challenges of reporting during WW2:

Post War Argument - testing and personalising the edges of impartiality

βImpartialityβ, somewhat compromised in practice but astonishingly wider than anyone might have expected, was one of the victors in WW2. The ΒιΆΉΤΌΕΔ became a hero and a model of public interest. But in the post-war period things shifted. Deference could not be taken for granted, and people were more demanding of their politicians. While there was a Cold War it did not impinge on everyday lives in the same way as the total war of the 1940s. The consumer society had different values from the past and people demanded more engaged and popular broadcasting, just as television was taking off. As they wanted to identify with presenters, impartiality faced new challenges of being expressed through individual voices.

Grace Wyndham Goldie was the pioneer of televised politics: balance was her mantra, as a tool to deliver impartiality in the new environment. The idea was that βon behalfβ of the viewer and listener, impartiality would become more active and inquiring. She started with the drama of the 1950 election and for the first time put the count on television, making stars of analysts like David Butler, then a young political scientist. Butlerβs innovative and visual understanding of βswingsβ and how to understand elections influenced democratic reporting of elections from the USA to India. In creating Panorama as the in-depth weekly investigation of a subject which was to be the βvoice of authorityβ, she said what was needed was: βResearch, research, research β impartiality depends on depth and context and not casual competition.β

Robin Day added interrogation as a new dimension of impartiality: the impartiality lay in the questions, the preparation, and the βwithout fear or favourβ approach. Day had a legal background so his sense of interrogation as forensic but impartial changed the terms of the interview:

βI only asked the questions for the audience and that the audience neededβ¦ it was not me but the public interest that challenged ministers.β

This new robust style of interviewing was revolutionary. Ministers had previously not been probed but invited to bestow their views on a waiting audience. In this way impartiality developed into a tool for holding politicians to account on behalf of the public.

William Whitelaw, a wily and public-spirited politician was close to Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher and talked about the impact that new interview techniques had on impartiality:

Northern Ireland: cost-heavy impartiality

Throughout the history of impartiality there is the problem of impartial between who and what. This has never been settled, nor should it be, as there are always alternative views to be found. This needs to be understood as a virtue since perfection cannot be achieved every time. Neither a defeat nor a compromise loses the need for this powerful method of exploration. But how could power be interrogated when it was outside conventional party politics? Nowhere was this tested more than Northern Ireland.

One director general, Hugh Carleton Greene, argued that the ΒιΆΉΤΌΕΔ should not equivocate over racism, prejudice and anti-democratic movements. His certainty was given urgency by his pre-war experience in Germany and the contemporary relevance of the exploitation of democratic institutions for authoritarian ends. Another DG, Charles Curran, argued for much of the 1970s about the nature of impartiality. Was there a wider way of looking at it than just between two public views? Curran argued forcefully that the differences should be reported but should not determine the agenda. The ΒιΆΉΤΌΕΔ, he suggested, was like representative democracy; it was interested in and careful of public opinion but obliged to seek explanations for views, and as it were βmake its own mind upβ despite the dangers.

The βTroublesβ that broke out in Northern Ireland in 1968 and lasted until 1997 with nearly 3,000 people killed, put unremitting pressure on how to deliver impartiality. In The Question of Ulster, an early and important test, the ΒιΆΉΤΌΕΔ had the temerity to broadcast a βtribunal of inquiryβ style discussion about community conflict and its remedies, despite the opposition of the ΒιΆΉΤΌΕΔ Secretary and unionist politicians. The diversity of those taking part, including some people with paramilitary associations, was an impartial recognition of reality. In doing so it was challenging the UK governmentβs capacity to define legitimate power.

Understanding the basis of power and the impact of political developments in Northern Ireland put βimpartialityβ under considerable strain but also brought an extreme governmental response. This impartiality came with a heavy cost. It brought the ΒιΆΉΤΌΕΔ into constant conflict with successive governments, from both sides, who said it was giving the βoxygen of publicityβ and legitimacy to βterrorists.β Governments wrestling with an intractable conflict brought great pressure on the ΒιΆΉΤΌΕΔ but so did competing community and armed groups. The ΒιΆΉΤΌΕΔ was subject to several bomb attacks. Governments threatened the ΒιΆΉΤΌΕΔ with licence fee cuts, and finally in 1988 imposed a broadcasting ban on speakers from proscribed organisations. This was condemned nationally and internationally, and broadcasters quickly found a way round it to continue to talk to banned organisations while sticking to the rules.

Locally some aspects of impartiality were reinvented. Dick Francis, ΒιΆΉΤΌΕΔ Northern Ireland Controller, commanded attention for impartial news in Northern Ireland by getting to what people needed to know first and putting it out fastest. Reporting was dangerous, bringing cost to journalists. Talkback, a robust phone-in programme in Northern Ireland, was an example of moderated listening, where all sides were heard. It was not βshock jockβ broadcasting because it brought sides together. People who worked for the ΒιΆΉΤΌΕΔ were said to leave their politics on the coat-stand as they came in and lived under constant physical threat and harsh political manoeuvring.

James Hawthorne who was Controller, ΒιΆΉΤΌΕΔ Northern Ireland from 1979-89 was central to some of the toughest disputes:

Impartiality: a work in progress

Some people argue that βimpartialityβ has always been little more than a sham, giving legitimacy to those in power. But the most intense pressure the ΒιΆΉΤΌΕΔ faces is normally from those in power, who wish for more compliance from the nationβs most prominent public service broadcaster. The response to such criticisms has always been for more adventurous impartiality.

Margaret Douglas who was Chief Political Adviser and Chief Assistant to the director general in the 1980s and 90s describes how the ΒιΆΉΤΌΕΔ faces attack:

Impartiality is neither fixed nor ever adequate. But it is the attempt to find out what really happened and what as wide a variety of points of view think that matters. Impartiality is not βbalanceβ - although balancing points of views is a useful tool - it is a discipline that attempts to reveal different perspectives on the way to understanding reality. As Orwell said βFreedom is the freedom to say that two plus two make four. If that is granted, all else follows.β

Identity, morality and impartiality

βIf journalists replace a flawed understanding of objectivity by taking refuge in subjectivity and think their opinions have more moral integrity than genuine inquiry, journalism will be lost,β says Tom Rosenstiel, Eleanor Merrill Visiting Professor on the Future of Journalism at the Philip Merrill College of Journalism, University of Maryland.

Impartiality never implied that the ΒιΆΉΤΌΕΔ should be balanced between untruths and reality. All views are equal views but not all views about everything are equally right. βHard impartialityβ captured a new version of the idea.

In 2007 ΒιΆΉΤΌΕΔ impartiality was updated in a report written by Richard Tait and John Bridcut: βIt remains an elusive, almost magical substance, which is often more evident in its absence than in its presence. Imagine twelve bottles on the alchemistβs shelf, with the following labels: Accuracy, Balance, Context, Distance, Even-handedness, Fairness, Objectivity, Open-mindedness, Rigour, Self-awareness, Transparency and Truth. None of these on its own could legitimately be relabelled Impartiality. But all the bottles are essential elements in the Impartiality compound, and it is the task of the alchemist, the programme-maker, to mix them in a complex cocktail.

Different proportions may be needed for different genres. But, as the Guidelines make clear, a mixture there must be, in every part of the ΒιΆΉΤΌΕΔβs output. The chemical reaction should produce not a solid (too rigid), nor a liquid (too fluid), but an odourless gas (harmless, of course) which will infuse the programme-making environment and be healthily breathed by those who work there. Impartiality is, after all, not a state of grace, but a state of mind.β

It proposed an extension of views, widened the scope of reporting and de-hierarchised the established views that should be considered.

Identity

Impartiality had to evolve again as a new generation of young reporters saw it as alien and tepid and less appealing than βcommitmentβ. They felt strongly and idealistic about issues, as ΒιΆΉΤΌΕΔ journalists always have, yet the moral voice of a Richard Dimbleby at Belsen, or a Charles Wheeler covering the American race riots, Allan Little in the former Yugoslavia or Mishal Husain at the Pakistan school shootings has been a powerful aspect of ΒιΆΉΤΌΕΔ journalism. Yet, the ΒιΆΉΤΌΕΔ can only serve the public by exploring, to the best of its ability, what has really taken place. The answer to the moral challenge which side of a genocide is the ΒιΆΉΤΌΕΔ on, is that the ΒιΆΉΤΌΕΔ is there to find out why and what has happened: both the larger, deeper causes and the immediate circumstances.

Impartiality is related to and yet not quite the same as objectivity, yet ΒιΆΉΤΌΕΔ news presenter Ros Atkinsβ βassertive impartialityβ, laying down facts in a row, is one example of the perpetual struggle to find out what has happened and to tell it to the public in new ways.

-

Ros Atkins On... A straight-talking style of analysis and explanation to distill one of the big issues in the news into just ten minutes.

Mark Thompson, a former director general told The Guardian in 2009: "I would rather the ΒιΆΉΤΌΕΔ was abolished than we started encrypting news to stop people seeing it," he says. "The absolute first building block keystone of the ΒιΆΉΤΌΕΔ is delivering impartial, unbiased news."

In 2022 director general Tim Davie spoke about the importance of impartiality to the corporation:

Written by Jean Seaton, Professor of Media History at The University of Westminster.

Links

Further reading

Patrick Barwise and Peter York, The War against the ΒιΆΉΤΌΕΔ. How an unprecedented combination of hostile forces is destroying Britainβs greatest cultural institutionβ¦And why you should care (2020).

Robin Aitken, Can we Trust the ΒιΆΉΤΌΕΔ? (2007).

Tom Mills, The ΒιΆΉΤΌΕΔ: Myth of a Public Service (2020).

David Edwards and David Cromwell, Media Lens Newspeak in the 21st Century (2009).

Leon Barkho (Editor), From Theory to Practice: How to Assess and Apply Impartiality in News and Current Affairs (2013).