During World War Two, the ΒιΆΉΤΌΕΔ German Service became a trusted and valuable source of information for millions of listeners in Nazi Germany. After the end of hostilities it was almost closed down, but the Foreign Office argued strongly for preserving it as a means of βprojecting Britainβ.

In response to the deteriorating international political climate, on 4th April 1949 the ΒιΆΉΤΌΕΔ German Service started a nightly βGerman East Zone Programmeβ (EZP) dealing with Cold War themes and specially targeted at listeners behind the Iron Curtain. The German Democratic Republic (GDR) was founded in the Soviet Zone in October of the same year, but the EZPβs name remained unchanged because Britain did not recognise the GDRβs existence.

German Service employee Fritz Beer explained in a memorandum that the three main goals of the EZP were to convince East Germans that they had not been forgotten, to assure them of the spiritual and material superiority of life in the west, and to fortify them against Eastern propaganda.

Broadcasting to the Eastern Zone presents in many respects, particularly in its political and psychological aspects, a more onerous task than did our war-time broadcasts to Nazi Germany.

Indeed, the EZPβs mission was a balancing act between accepting the geopolitical status quo and reflecting the fact that its Foreign Office funders did not accept the legitimacy of East Germanyβs communist government.

Another influential factor in the ΒιΆΉΤΌΕΔ German Serviceβs postwar output was the fact that Γ©migrΓ© staff such as Carl Brinitzer, Bruno Adler and Robert Lucas (born Robert Ehrenzweig) were veterans of its wartime broadcasts, and a number of their early features were essentially re-workings of popular anti-Nazi satirical sketches, albeit with different titles and premises.

As in World War Two, programmes such as βThe Two Comradesβ (1949-1963) and βThe Baffled Newspaper Readerβ (1950-1972) tried to drive a wedge between the Party and ordinary citizens, using satire and irony to demonstrate the chasm between political dogma and the realities of everyday life. The talks of the communist poet Erich Fried, meanwhile, negatively contrasted βreal existing socialismβ in the GDR with the original ideals of Marx and Engels.

Unlike the American stations broadcasting to Eastern Europe such as and , the ΒιΆΉΤΌΕΔ pursued a policy of non-intervention and did not advocate an active uprising.

Nonetheless, in 1959, Ralph Murray of the Foreign Office and future Governor of the ΒιΆΉΤΌΕΔ wrote that the EZP βseems to me sharper in tone than any other Service I have ever been aware of, and goes to lengths of exhortation or implied exhortation to the population of the East Zone which would I think get us into trouble with practically any other government.β

Inevitably, over its 25-year lifespan the EZP did in fact consistently attract the ire of the GDR authorities, as when Politburo member Albert Norden complained about its output in a letter to Labour MP Richard Crossman in 1963.

What the ΒιΆΉΤΌΕΔ is doing, is direct meddling with the internal affairs of our State. The ΒιΆΉΤΌΕΔ calls systematically for the overthrow of the existing social and political system and for the removal of members of the GDRβs government.

In the 1960s, the EZP was more neutrally renamed the East German Programme and attempts were made to appeal to a younger generation of listeners.

Youth in the GDR were no more immune to the rock nβ roll craze than their British counterparts, and the lively musical request show βeine kleine Beatmusikβ featured dedications to friends or sweethearts, often using popular pseudonyms, such as greetings βfrom Mick Jagger in KleinkΓΌhnau to sweet, tender Marion in Dessauβ.

East Germanyβs secret police, the Stasi, saw this identification with western popular culture as part of a broader strategy to isolate young people from GDR society. A confidential 1961 report claimed that both RIAS and the ΒιΆΉΤΌΕΔ German Service were encouraging juvenile listeners to become dependent on western news sources, βthus inevitably bringing them into conflict with social conditions and social organisations in the GDRβ.

The crux of the Stasiβs campaign against the ΒιΆΉΤΌΕΔ, codenamed Operation βWerferβ (βThrowerβ), was the Soviet newspaper Izvestiaβs publication in 1968 of documents that detailed specific liaison arrangements between the ΒιΆΉΤΌΕΔ and the British Secret Intelligence Service, MI6.

In a newly released oral history interview with the head of the at the time, Alexander Lieven describes Soviet attitudes towards ΒιΆΉΤΌΕΔ broadcasts and the impact of these on ΒιΆΉΤΌΕΔ staff.

The arrangement included procedures, reminiscent of the wartime system for transmitting code messages to undercover operatives and the resistance, whereby MI6 could request the insertion of music and messages into broadcast output. It also allowed for mail received by the ΒιΆΉΤΌΕΔ from Eastern bloc countries to be passed on for assessment before being returned unmarked by the Foreign Office.

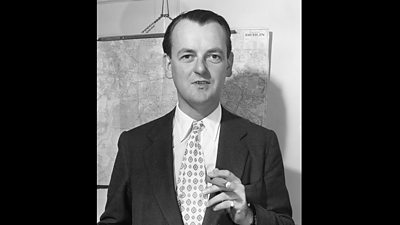

And listenersβ letters provided the material for the EZPβs most popular feature, βLetters without Signatureβ (1949-1974), which became the Stasiβs main target. These broadcasts consisted of letters about everyday life in the GDR, which were read out by actors and then commented on by the programmeβs longtime writer and presenter Austin Harrison.

βLetters without Signatureβ created a sense of community among otherwise isolated critical East Germans, although pro-GDR and anti-ΒιΆΉΤΌΕΔ letters were also read on the air.

However, the Stasi considered Harrison to be an MI6 operative, a βrefined and experienced opponentβ whose task was to collect political, economic and cultural information and make contact with potential agents in the GDR during his annual visits.

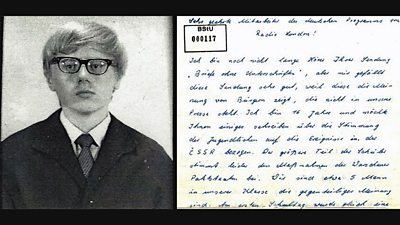

Letters were sent to an ever-changing series of cover addresses in West Berlin (actually World War Two bomb sites), and Harrison gave listeners tips for keeping what the Stasi called βconspiratorial rulesβ, including the use of a codename and providing no information that might allow the letter to be traced back to its author.

Many letters were intercepted and forensically analysed by the Stasi. The consequences for letter-writers who could be tracked down included prison sentences, as in the case of the schoolboy Karl-Heinz Borchardt.

In the political thaw brought about by dΓ©tente, however, what one disapproving British listener had described as the βobsolescent Cold War attitudesβ of the East German Programme were being overtaken by political events.

By 1973, Britain had recognised the GDR and established an Embassy in East Berlin. One year later βLetters Without Signatureβ was discontinued, followed in 1975 by the East German Programme itself. Only an all-German Service remained, broadcasting to East and West Germans as one. It would be another fifteen years until this, too, was reflected by the political reality of unification.

Written by Dr Will Studdert, Visiting Scholar at the Centre for British Studies, Humboldt University of Berlin.