Bangladesh ranks 163rd in the world in the Press Freedom Index and journalists face difficult working conditions, with poor pay and little job security. 麻豆约拍 Media Action has been working through Protecting Independent Media for Effective Development (PRIMED) to support local media associations in their efforts at change. In this third of three articles, our guest blogger Udisa Islam, special correspondent for the Bangla Tribune, examines the issue of gender equality in media in Bangladesh.

The time has come to question how Bangladesh’s media outlets are navigating gender equality. Our mass media has reached adulthood, after a history of ups and downs. One significant way to measure the maturity of media is its sensitivity to issues of gender. We need to find solutions to the questions of why the media should become gender-sensitive, and how.

It is time to talk about the presence of women in media, the representation of women in media, and the working environment for women working in media.

It is cliché to state that journalism is challenging. Since the beginning of my work in the media, I have often heard that women face greater risk in this profession. In a country like Bangladesh, where only 12 percent of households are led by women and men retain most decision-making roles, it can be a challenge just to comprehend a woman’s life and identity outside the domestic sphere.

According to ’s (MRDI) recent research, women journalists are facing discrimination, directly or indirectly, in media in Bangladesh. Only 10 per cent of media’s staff here are women, and very few are in decision-making positions. They recommend that to address this, media experts, society leaders, and development partners must work together.

Gender sensitivity in presentation and presence

But what about how women are represented in media? According to the MRDI study, most news stories including women do so either because they are in an important position, or part of an event. In most news stories, women are either the subject of the story or narrators of their experiences. Representation of women as experts is extremely rare, particularly in stories about politics and governance. However, in news about violence and torture, women are shown excessively.

Now let's examine gender sensitivity in presentation and presence. There have been positive changes identified, for instance, around how women are described, and ensuring that women who are abuse survivors can rely on anonymity in media. However, if we consider the rate at which our media has grown since 2000, this particular progress fails spectacularly to become noteworthy. As long as patriarchy is ingrained in our brains, simply 'following the rules' and behaving sensibly will in itself prove to be a Herculean task. If we do not adopt gender sensitivity in our own behaviour and personal life, then these negative habits are bound to be conveyed in media in one way or another.

How to achieve change

We like to think that we are learning to become 'gender sensitive', and taking training to learn it, and we have the opportunity to converse about these topics. But then, we are failing to remove the concept of patriarchy from our brains. As a result, overall and fundamental change is still a long way off.

However, if someone enters to journalism after preparing to become a more gender-sensitive person, follows ethical practices, and if there is an institutional practice of good journalism, then the number of women in media will increase and the representation of women in mass media will also change.

But as long as our media remain separated from this way of thinking, true freedom in representation might never become a reality.

Udisa Islam is a Special Correspondent for the Bangla Tribune. She can be reached at udisaislam@gmail.com.

Read the first blog in the series here - and the second here.

Read more about PRIMED here.

]]>Bangladesh ranks 163rd in the world in the Press Freedom Index and journalists face difficult working conditions, with poor pay and little job security. 麻豆约拍 Media Action has been working through Protecting Independent Media for Effective Development (PRIMED) to support local media associations in their efforts at change. In this second in a series of three articles, Bangladesh Global TV Editor in Chief Syed Ishtiaque Reza explores recent findings on working conditions for journalists in Bangladesh and discusses the pressures on local media.

"In our childhood, affluent people used to keep pet dogs. Later, people who gained wealth started to keep media.

These [media] are like Alsatian dogs."

This was a remark by a top politician at a public meeting in Bangladesh. This lawmaker is not alone. Many politicians and social stalwarts on many occasions make such disparaging remarks about journalists and the profession in general. And, in our sharply divided political environment, Bangladesh’s journalist community is also divided by politics. There are two trade union bodies, each with its own political allegiances..

Media are under political, economic and legal threats in Bangladesh. The economic impacts of the COVID—19 pandemic and of rising oil, food, fertiliser and other commodity prices due to the war in Ukraine is visible in every sector of the economy. This has sparked a cost-of-living crisis in Bangladesh, drained the central bank’s reserves at an alarming rate, and led the government into harsh austerity measures.

This has disrupted the media industry too. A new survey found that journalists from across the country are bearing great personal financial impact from this situation.

Economic calamity for media houses

Bangladesh media traditionally operates in a difficult environment. Even before this situation, media revenues were falling. The pandemic followed by the war’s impact on the national economy has just accelerated this deterioration, resulting in an economic calamity for media houses. The rise of social media and acceleration in mobile consumption have also forced changes in the way media companies usually make money, from advertising and selling their content.

According to data from the Information Ministry of Bangladesh, there are now 44 approved television channels, 22 FM radios, 32 community radios, 1,187 daily newspapers and more than 100 online news portals in Bangladesh.

A recent survey conducted by Broadcast Journalists’ Centre (BJC) among 23 television channels produced a very dismal picture of the broadcast industry. Only eight percent of television networks pay their employees regularly by the 10th of the month and only 50 percent of the channels pay festival bonuses. Only one television outlet has introduced gratuity benefits for employees, common in other industries as a reward for service. As many as 13 media houses have systems to terminate their employees without giving prior notice. Eighteen channels don’t cover medical expenses for on-duty injuries. There are no weekly and public holidays in 11 percent of the television channels. Almost all pay nothing for annual leave. The BJC survey also revealed that journalists do not talk about their legal rights, for fear of losing their jobs.

Ads drying up

With businesses closed, advertisements have dried up, adversely affecting the routine operation of the media industry. Media houses’ overall approach now is to tighten their belts. Newspapers have reduced pages; television channels have reduced their commissions. Their main focus is now low-cost talk shows on Internet platforms with live coverage for hours. Some newspapers and online portals have dismissed employees, while some have sent employees on forced leave.

Complicating media sustainability is that, over the past few decades, people with access to the corridors of power in business and politics have traditionally successfully influenced the dissemination of information through media houses, by owning a majority share in these outlets. They influenced content for their own interests. Media ownership significantly affects the perspectives presented in reporting, with bias and inefficiency then inevitable.

And now, the situation is allowing more opportunities for government voices and administrators to occupy spaces in media.

Failing to generate digital revenue

A few media houses have succeeded in drawing revenue from the digital space. But many have failed. Bangladesh’s media industry needs financial remodelling with more institutional approaches from the owners. Televisions and newspapers will not reach people without content that meet audiences’ demands.

We believe that political or business capture of the media cannot continue for long. People’s engagement with media is high; they seek quality information from reputable providers. Younger people have grown up with Internet culture; their desire to consume and pay is an indication of improving value. Connecting to this segment of the population will convince advertisers to invest more in reliable content. I have seen that the younger generation will pay for news - but they want more independent and public interest content.

Love what they produce

It is said that the media love a crisis. But now the media need to love what they produce: they must remain true to their mandate of public interest content. Without good journalism, the media here will simply die out; the current situation is a red signal to conventional media approaches. Digital professionals, digital audiences and digital platforms have come together to prioritise professionalism, and journalism for the people. And media houses must consider this in their business development strategies, in order to survive and think about their own value.

Today the media landscape is in real crisis – we have media against media, political challenges and even civil society challenges. All of these relationships are in urgent need of repair, redress and balance. We know that freedom without responsibility is as bad as governing without accountability. This extraordinary episode in time must serve as a reminder of this truth to us all.

Syed Ishtiaque Reza is the Editor in Chief of Global Television. He can be reached on ishtiaquereza@gmail.com

Read the first blog in the series here - and the third here.

Read more about PRIMED here.

]]>

Bangladesh ranks 163rd in the world in the Press Freedom Index and journalists face difficult working conditions, with poor pay and little job security. 麻豆约拍 Media Action has been working through Protecting Independent Media for Effective Development (PRIMED) to support local media associations in their efforts at change. In this series of three articles, we examine recent findings on working conditions, and hear directly from local journalists about the pressures on local media, and how to address gender representation in media.

The COVID-19 pandemic ended Selim (not his real name)’s 12-year career in television.

But Selim received no compensation or medical insurance from his former employer. And he was not alone: countless TV reporters in Bangladesh faced the same fate, due to the lack of a separate labour law for broadcast journalists in Bangladesh. Others who retained their jobs received irregular payments; most outlets did not follow national wage board structures.

Data from a recent survey conducted by the Broadcast Journalist Centre (BJC) shows the ‘fourth pillar’ of our state is at risk: their labour rights are not being protected, at outlet and national level.

Free press and media are crucial components of democracy. While celebrating the fundamental principles of press freedom, including freedom of expression, as a driver for all other human rights, it is critical to also consider the neglect of basic employment standards for broadcast journalists in Bangladesh – and the subsequent impact on the media environment in the country.

According to data from the Information and Broadcasting Ministry, in Bangladesh, there are 44 approved televisions, 22 FM radios, 32 community radios, 1,187 daily newspapers, and more than 100 online news portals. The survey done by BJC covers only 23 TV channels – but sheds much light on working conditions and benefits provided.

Irregular pay, no benefits

The Broadcast Journalism Safety Report 2023 reveals some staggering figures. Among the stations they surveyed, only 8% pay regular salaries within the 10th day of every month, and 92% failed to pay salaries to journalists regularly. Only 2% of the channels had health and life insurance benefits for their employees; only 3% had created retirement funds. An estimated 12% of the channels had provisions for maternity leave and just 1% for paternity leave. And threats of lay-off loom large: 93% of the channels were reported to have fired employees without any prior notice, while 98% of the channels did not offer any compensation to dismissed employees. The report indicates that the Bangladesh Labour Act of 2006 is insufficient in protecting broadcast journalists’ rights.

The media industry in Bangladesh has evolved so much. But gender equality also remains a concern, both at media outlets, and in their content. A recent study done by MRDI shows female journalists face active and passive discrimination at work. Only 10% of total employees in organisations surveyed are women, and very few are in decision-making roles. Most outlets also do not have any written editorial guidelines to ensure fair and ethical treatment of women.

麻豆约拍 Media Action aims to support all media outlets and their media professionals to practice stronger public interest journalism, so they can produce trusted content that keeps the audience at its heart. Our Protecting Independent Media for Effective Development (PRIMED) project is working to support the development of a healthier information ‘ecosystem’, addressing challenges for media outlets and in the broader information environment. This includes a series of workshops on gender representation in content and safeguarding and respect in the workplace, as well as addressing regulatory challenges. Through PRIMED 麻豆约拍 Media Action also supported its media partners to develop written editorial guidelines.

A new law

Recently, an initiative has been taken by the Government of Bangladesh to introduce a new law covering television journalists, the Mass Media Employees Bill. The Broadcast Journalist Centre (BJC) and other media associations are now advocating for changes to create a more inclusive and effective bill that truly protects their rights.

麻豆约拍 Media Action and International Media Support (IMS) have been providing technical support to BJC to identify gaps and develop concrete recommendations, while empowering local and sector partners to drive forward positive change for media reform and protecting journalists’ working conditions.

The sector is encouraged by a response to this report from the Minister for Law, Justice and Parliamentary Affairs, who acknowledged the needs and expressed his interest in a multi-party consultation among the owners of broadcasting channels, journalists, and representatives from the standing committee, with an eye to revising the law.

Critical need for trust

Right now, there is a critical need to retain and restore public trust in mainstream media in Bangladesh. BJC is developing a Code of Ethics for the industry with the technical support of 麻豆约拍 Media Action and IMS, aimed at improved editorial practices for all TV networks.

The combination of increased safety and security at work for journalists, and an entrenched and shared understanding of ethics, can truly boost public interest journalism.

This is the first blog in a series of three from Bangladesh. Read the second here, and third one here.

Read more about PRIMED here.

]]>Just over a year on from the first Summit for Democracy, the backdrop for this year’s event – co-hosted by the United States, the Netherlands, South Korea and Zambia – is both very different, and depressingly similar.

It is entirely different in that the Russian invasion of Ukraine has prompted concerted and deep seated effort among democracies committed to showing common cause with extraordinary Ukrainian resistance against autocratic invasion. As recently as 18 months ago, these same countries were still fractured and quarrelsome over issues as diverse as procurement of submarines and COVID vaccines. Today, and with some exceptions, they are mobilising with a fresh shared purpose in defence of the democratic idea, and in resistance to a country where control of ideas has become a defining and depressing mission.

But the backdrop to this Summit is also all too familiar in that most indicators suggest democracy as an idea remains in retreat. Autocracy as a force for organising societies in the interests of unaccountable power remains on the march. The latest V-Dem report on the state of democracy in the world makes for gloomy reading, reporting a new record of 42 autocratising countries - up by nine from the 33 reported in last year’s Democracy Report, which was itself then a historical record. For the first time in more than two decades, the world has more closed autocracies than liberal democracies.

A constant theme

There are other similarities. Attacks on independent media - the strategy used by autocrats to seize and control power – have become a constant theme in any analysis of democratic decline in recent years.

“Aspects of freedom of expression and the media are the ones ‘wanna-be dictators’ attack the most and often first,” finds V-Dem. “At the very top of the list, we find government censorship of the media, which is worsening in 47 countries.”

Autocracy is at risk of becoming a global norm and the route to its advance follows a clear, predictable and demonstrably very successful strategy: first and foremost, intimidate and co-opt the media, and second, deploy disinformation to polarise and divide society. “Autocratising governments are those that are increasing their use of disinformation the most,” finds the report. “They use it to steer citizens’ preferences, cause further divisions, and strengthen their support.”

A press conference in Ukraine

Signs of collective response

There are some signs that democracies are just beginning to recognise this and to respond collectively and determinedly, beyond the many fragmented initiatives which have characterised democracy support in recent years. One of the principal outcomes of the first Summit for Democracy was US President Joe Biden’s leadership in being the first country to commit substantial resources – up to $30 million – to a newly established International Fund for Public Interest Media (IFPIM).

Other heads of state committing resources included then-Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern of New Zealand and President Emmanuel Macron of France; countries as diverse as Taiwan, South Korea and Switzerland have also pledged their support. UN Secretary General Antonio Guterres had earlier his support for the Fund’s establishment.

IFPIM, originally suggested by 麻豆约拍 Media Action, is now an independent entity that has raised almost $50 million and is being established in Paris, with a board co-chaired by Nobel Peace Prize winner Maria Ressa and former head of the 麻豆约拍 and the New York Times, Mark Thompson. In addition to a promising and significant source of new finance for independent media in low- and middle-income countries, IFPIM is positioning itself as a symbol of multilateral cooperation in defence of democracy. With support and representation from a broad range of countries, it aims to move beyond the idea that democratic defence is a preserve of the “West” – that, rather, democracy is a universal value and some of its greatest advocates can be found where upholding it is often most challenging.

A slow financial response

All that being said, autocrats still have it depressingly easy and the financial response required to protect independent media around the world is still being mounted by just a very small number – principally the US, Sweden, Switzerland and now France. Several are actually reducing their support. Total support as reported to the OECD stands at just 0.3% of development assistance; miniscule amounts of that support actually finds its way into the coffers of independent media who are under increasingly existential economic, as well as political, pressure.

The COVID pandemic made the autocratic task of undermining media easier still, as already crumbling business models further undermined the resilience of independent media. “In low- and middle-income countries, where many outlets operate in an unstable business environment and have limited access to investment capital, philanthropy and government support, the pandemic threatens the fundamental existence of free, fair, independent news media ecosystem,” found a major 2022 published by UNESCO and the Economist Intelligence Unit.

麻豆约拍 Media Action is proud of the role it has played in helping to seed IFPIM, which is now entirely independent, and of other work to support independent media around the world. This has included, for example, facilitating the creation of a National Action Plan on independent media in Sierra Leone, and advising the Indonesian government on a new Presidential Regulation for Publishers’ Rights, ensuring media outlets are paid by the digital platforms and aggregators that carry their content.

An existential financial threat

But efforts like these, and those of other media support responses, cannot succeed unless there is a clear recognition of the existential financial threat that most independent media face. For that to happen, many more countries need to step up their currently negligible contributions to media support. Given the small sums involved, and the immense contributions of independent media to defending democracy and resisting autocracy, these are some of the best value-for-money investments possible.

A similar tide needs to turn on disinformation and toxic polarisation. 麻豆约拍 Media Action is playing a key role here, too.

V-Dem has recommended that, to counter autocratisation, “pro-democratic actors could pursue strategies such as dialogues and civic education seeking to reduce political polarisation and to increase citizens’ resistance to the spread of disinformation.” We work at scale, providing support to more than 250 media partners worldwide to effectively disseminate trustworthy information while scrutinizing and exposing propaganda and disinformation. Last year, we reached over 120 million people with programming designed to encourage debate, dialogue and access to trusted information across divides. We are currently conducting research to gain insight into the factors that influence people's beliefs and their tendency to share information with others. In partnership with the University of Cambridge, we are working to support the creation of content that can scale up the application of ‘inoculation theory’ as a pre-bunking approach to build people’s resilience to mis- and disinformation theory to help prevent the spread of false or hate-filled narratives and news.

Glimmers of light

The tide may look like it is going out on democracy. But there are glimmers of light emerging, and not just with resistance to Russia. Many of the trends V-Dem highlights can work in reverse. It argues that while “disinformation is like a stick used by anti-pluralist parties to stir up polarisation,” the opposite also holds true: as democratisation takes hold, governments find it ever more difficult to spread disinformation.

If democracies all over the world can continue to find common cause, to work together rather than at odds with one another, to establish new multilateral institutions like IFPIM and take maximum advantage of innovation in combatting disinformation, the autocratic wave can be reversed. But there is a long way to go before that becomes reality.

---

James Deane is Head of Policy at 麻豆约拍 Media Action. He has spent much of the last three years working with others to develop the International Fund for Public Interest Media.

Our challenge: How do we ensure families in India have timely information about childbirth, childcare and family planning, during pregnancy and in the first year of the child's life?

The innovation: High-quality health information and advice to Indian families - particularly in rural areas – through the growing use of basic mobile phones. Our human-centred design mobile health solution has been scaled to 17 states by the Government of India to empower families and frontline health workers to improve child mortality and maternal health.

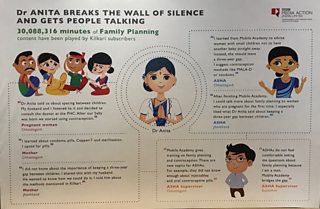

Kilkari (a baby’s gurgle) is our mobile messaging service designed to reinforce frontline health workers’ counselling by delivering information to families to help healthier choices and lives. Combined with tools and training for frontline health workers – our Mobile Academy training course, and Mobile Kunji tool to support frontline workers in communicating with families - the service is strengthening this ‘last mile’ of the health system, to increase their knowledge, skills and confidence in communicating, and reinforcing their information. Aiding with all of this is the trusted voice of ‘Dr Anita', the fictional narrator across our suite of mHealth services – Mobile Academy, Mobile Kunji and Kilkari – providing health information, guidance and friendship to families across India.

Kilkari’s free, weekly, stage-based audio messages about pregnancy, childbirth, childcare and family planning are delivered directly to families’ phones as one pre-recorded call per week for 72 weeks, linked to the stage of pregnancy or child’s age and timed for the highest-risk periods, between the second trimester of pregnancy until the child is a year old. Available in five languages – Hindi, Bihari, Oriya, Assamese and Bengali – family mobile phones are automatically subscribed as soon as a pregnancy is registered in the government database.

Following two independent evaluations and analyses from Johns Hopkins University and Stanford University, now published in a special supplement of , here are the lessons we learned over a decade of digital development:

Dr. Anita is the fictional narrator of Kilkari, Mobile Academy and Mobile Kunji, providing health information, guidance and friendship to families across India.

1. Mobiles can provide access to health information at scale using appropriate technology

Kilkari is one of the world’s largest mobile maternal messaging services and has reached 24.6 million subscribers across 17 states. Mobile Academy is the largest mobile-based training programme for health workers in the world and has reached over 235,000 frontline health workers across 16 states in India. Amid low levels of smartphone access and ownership among women in low-income and low-literate settings, both services use IVR (Interactive Voice Response) technology to help overcome these challenges.

2. Timed and targeted information can improve modern contraceptive use and immunisation

When Dr Anita gave advice on condom use, people listened: Those who listened to Kilkari were associated with a 3.7% higher use of modern reversible contraceptives; the number rose to 7.3% among those who heard 50% or more of Kilkari content, compared to non-listeners – largely driven by increased condom use. Effects were even larger for families with a male child (9.9% increase), in the poorest socioeconomic strata (15.8% increase), and in disadvantaged castes (12.0% increase). The evaluation also found higher rates of immunisation among infants at 10 weeks (2.8%).

3. A relatively small amount of the relevant content, delivered at the right time, is a cost-effective way of saving lives

Seven Kilkari calls on reversible contraceptive methods, totalling just over 10 minutes and delivered direct to families’ mobile phones, had an effect on those families’ practices. Peer-reviewed analysis of our randomised controlled trial showed that Kilkari has saved nearly 14,000 lives (96% child lives and 4% maternal) and has been declared a highly cost-effective intervention, with the cost per life saved ranging from USD $392 to $953 depending on the intervention year.

4. Design mHealth solutions with an equity lens to reach the poorest communities with mobile phone access

It’s important to think about how communities are using mobile phones, and when. The poorest subscribers, educated to at least secondary level, appear to have had the biggest equity gains from exposure to Kilkari, thanks to design decisions like the ‘retry’ algorithm – which tried mobile phone numbers at different times of the day, to reach families when they had time to listen.

5. Subscription-based business models are challenging in low-resource settings

In the initial years, Kilkari subscribers were charged a nominal fee – but this user-fee model failed to cover marketing costs. Kilkari became a toll-free service in 2016 with call costs covered by the Government of India, enabling greater reach and impact.

6. Digital interventions must be informed by gender intentional design

The gender digital divide in India, and the offline and online norms that create this divide, necessitate a gender-intentional, research-driven approach to designing mHealth interventions. We needed to understand who is left behind by digital interventions - and how to reach and impact those groups through alternate communication channels and platforms.

7. Digital direct-to-beneficiary communications need to be complemented by a mix of other interventions to shift social norms and change deeply entrenched behaviours.

Despite advice that covered a full range of infant and childcare, Kilkari was not found to have had measurable impact on infant and young child feeding practices. Our evaluators found that practices under ‘normative influence’ – where families do not need to engage with the health system, like complementary feeding - saw more positive associations when communication tools like Mobile Kunji were used, providing opportunity for further discussion.

--

This article was first written in November 2022 and updated in March 2023.

Kilkari is one of only five mHealth services globally to reach over one million subscribers and won ‘Best mobile innovation for women in emerging markets' at GSMA Global Mobile Awards 2019. Learn more about Kilkari on our website, in the (third-party site) and at the International SBCC Summit from December 2022.

Calculations on lives saved and cost effectiveness appear by LeFevre, A.E. et al, ‘Are stage-based, direct-to-beneficiary mobile communication programmes cost-effective in improving reproductive and child health outcomes in India? Results from an individually randomised controlled trial of a national programme.’

We are grateful to Stanford University for analysis of our evaluation, and to Johns Hopkins University for conducting the randomised controlled trial.

Sara Chamberlain is currently on sabbatical as India Digital Director; Radharani Mitra is India Creative Director and Global Creative Advisor; and Anna Godfrey is Head of Evidence at 麻豆约拍 Media Action.

Learn more about Kilkari and its impact.

A Rohingya refugee camp in Cox's Bazar, Bangladesh. Mrittika Deb Purba/麻豆约拍 Media Action Bangladesh

Cox’s Bazar is the home of more than 900,000 Rohingya people living in refugee camps, of whom an . We recently conducted with people with disabilities living in the camps, to understand what barriers they face in accessing information, participating in decision-making activities, making complaints and giving feedback to the humanitarian agencies working there.

“Invisible” people in Rohingya camps

During our fieldwork, we realised how hard it was to find people with disabilities to talk to in the Rohingya camps. It was difficult to find people with disabilities in public spaces – as if they were invisible - and when asking other camp residents where we might find people with disabilities, we had to use disparaging terms for them to understand who we meant, as they are often referred to only by their impairments. We also sought support from humanitarian practitioners working with this group, to help us identify potential research participants.

Once we found participants to speak to, we observed that most of their shelters were located either up steep hills, or beside drains. And the roads to reach their shelters were typically unstable and uneven. We wondered: if we are struggling to get to them on foot, then how are people with a physical disability managing to get around? Are they able to move from their shelters? As it was the rainy season, another question came into our minds: if there was a landslide, how fast would people with disabilities be alerted to the danger, and would they be able to move when the roads are slippery and muddy? When we reached their shelters, we noticed that often families would keep women with disabilities (especially those with hearing, vision and learning impairments) ‘out of sight’ in dark parts of the shelter, with little air, which was not the case for men with disabilities. We asked ourselves – why is it that women with disabilities are kept hidden from view by their families?

Barriers aggravate their “invisible” condition

Our research identified that people with disabilities face a series of barriers in accessing information, beginning at home. They often do not know where to get information, which makes them dependent on their family members or caregivers. And even if they know where to go, they are often not permitted to go out alone, as family members fear they will injure themselves on the slippery mud or steep slopes - even if they do not have a physical disability and are able to walk themselves. Instead, family members may try to carry them themselves, or seek assistance from neighbours to carry them; however, neighbours may charge for this help, which families may struggle to afford.

Stigma is another barrier to going out: people with disabilities and their families fear being humiliated by other community members, and have experienced abuse, from being calling discriminatory names to having stones thrown at them. Because of this stigma and abuse, family members are often reluctant to accompany people with disabilities outside, and sometimes people with disabilities may hide themselves from the community.

To minimise these barriers, organisations working to support people with disabilities have mobile teams and door-to-door services to reach people with disabilities with information. However, our research identified further barriers. The mobile teams are often staffed by a limited number of community volunteers, who may be unable to cover the whole camp, and so do not reach people with disabilities who live in more remote areas. When they do reach people’s shelters, they may ask family members or caregivers about the problems or concerns of the person with disabilities, rather than checking with the person themselves. When we asked practitioners working for organisations supporting people with disabilities about this, they explained that family members often have mechanisms to communicate with their disabled family member - for example, if that person is hearing impaired and does not use international sign language. However, this excuse is not relevant for someone with a disability which is not communication related.

Negative experiences at sessions

These barriers, throughout the year, constrain people with disabilities from participating in any meetings in the camps, excluding them from decision-making processes. We did find that some research participants had attended awareness-raising sessions – even though they were organised far from their homes. But some said their experiences were so negative that they were unwilling to attend further meetings.

A 32-year-old woman with a vision impairment told us:

“When we arrived at the meeting, the volunteer said that the meeting was not for me and I requested her to let me enter as I cannot go back alone. She let me enter and asked me to sit in a corner of the room. When they start meeting, I was having problems hearing clearly so I asked my neighbour what she just said. And that time, the community volunteer shouted at me for interrupting her discussion. Her behaviour made me sad and after that day, I never went to any meetings."

Afraid to ask questions

We heard these kinds of examples from both male and female participants with physical, visual, and hearing impairments. These experiences affected their desire to participate and be heard. They told us they often don’t ask questions, because everything is new to them, and they lack confidence asking questions of those they perceive as more educated. Some said they feel shy talking in front of people without disabilities.

We have learned from our research that we all need to increase our efforts to be more inclusive in the way that we communicate with these ‘invisible people’ to ensure that they have the accessible information they need and are able to participate in decision-making forums. Humanitarian agencies are scaling their support for people with disabilities in the camps. But now, in the fifth year of the Rohingya refugee crisis, more effort is required to understand their experiences, fears and needs, and address their barriers, so that they feel confident and empowered to communicate with, and participate in, the wider community.

A fully inclusive response

Humanitarian actors should take steps to make their response fully inclusive: ensuring a smooth and accessible information flow within the camps so that people with disabilities can obtain information without difficulty; supporting experts so they are better able to communicate with people with disabilities; focusing on sensitising and educating communities to reduce stigma against people with disabilities; supporting people with disabilities to participate meaningfully in meetings; and mentoring caregivers to be a strong support rather than a barrier to participation. 麻豆约拍 Media Action could play a vital role in this work: through developing and sharing relevant content which is accessible for all, and features people with disabilities, and training humanitarian staff on interpersonal communication skills and inclusion, to ensure they are reaching everyone.

Indonesia is one of the youngest offices of 麻豆约拍 Media Action. One of our projects is focused on green growth and climate change and is aimed at young people. On social media platforms, our brand, (Our Action) is sharing compelling information and insights, reaching millions and sparking conversations amongst our audiences across the Indonesian archipelago through Instagram, Youtube, Tiktok, and Twitter.

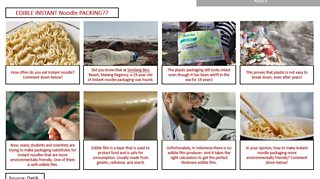

We’ve found that the best way to communicate about such issues and how they're affecting each one of us is by using aspects of everyday life that young people can easily relate to.鈥嬧€嬧€嬧€嬧€嬧€嬧€�

Tasty and... forever?

Who doesn’t love instant noodles? Quick, easy, delicious.

In Indonesia, they are very popular, people eat them every day, and the most well-known brand - which is exported widely - is almost part of our national identity.

One of the most successful stories we produced used instant noodles as a hook. The first part of the story showed the problem: people finding a 19-year-old instant noodles plastic packaging on the beach – unchanged, intact. Indestructible.

The second part of the video focused on the solution. It presented environmentally friendly packaging material produced by scientists as an alternative to plastic packaging.

You can see the video .

How we raised the issue of the indestructible instant noodle package

The impact?

So far, the packaging of instant noodles has not changed. But at least we have started the conversation.

The video went viral and reached more than four million people on YouTube alone. Young people are talking about it on social media and the viewership is increasing by the day. Indonesians today are more aware of how their consumption can be detrimental to their environment - including these noodles. 鈥嬧€嬧€嬧€嬧€嬧€嬧€嬧€嬧€嬧€嬧€嬧€嬧€嬧€�

On Twitter, people joked about the good quality of the packaging that is indestructible, but they also discussed the price that we pay for eating plastic-packaged instant noodles. Our research showed that people not only found it relatable but were surprised that something they do every day could have such an impact on the planet.

We never expected the video to go viral. We’re used to videos of celebrities going viral, but not instant noodles. What we learned is something we talk about all the time at the 麻豆约拍, "using something people can relate to". It works.

So we did it again with Grandma’s biscuit tin – another very popular video.

Simplifying communications around upcycling.

Who doesn’t remember their disappointment during their childhood when they would open the biscuit tin only to find that their granny had put cheap crackers in it, or even worse, a sewing kit?

This shared moment of early sorrow helped to create feelings of nostalgia within the viewer, and then, the upside: look… even Grandma was an environmentalist.

In our re-telling of this common story, we had a young person repurposing the tin and upcycling it.

You can watch the video .

How Granny is an environmentalist - by upcycling the biscuit tin

Now that we built a fanbase of more than 181k on social media, I would say we need to take the next step and engage with people outside the social media sphere. We need roadshows and live discussions so we can get young people to take action as a community rather than individuals.

Research is vital to knowing what your audiences will like and making this an entry point to your programme is key to success. In Indonesia, youth are tech-savvy, but they also want to engage online, build their identity, and talk about food, fashion, and music – not just climate change.

--

Find out more about our project Kembali Ke Hutan (Return to the forest) here .

Read our research evaluation briefing about the project .

Kembali Ke Hutan is funded by .

For more than a decade, 麻豆约拍 Media Action has worked to support young people in Cambodia – on issues including sexual and reproductive health, and job-hunting skills in a difficult labour market. We’ve done this through our brands Loy9, Love9 and more recently Klahan9 (Brave 9) – engaging young people where they are, through reality TV, social media and in road shows.

In 2020 we wanted to focus on how to engage more young people in civic life. We knew that people were hesitant to participate in public life, didn’t discuss politics and civic issues with others, and were fearful of doing so. When we had conducted research on this topic before, people were very reluctant to talk to our researchers, too.

We wanted to develop a deeper understanding of different groups of young people, exploring what they know about how they can participate, whether they discuss civic issues, what attitudes and norms affect their participation, and who influences their actions. We also wanted to understand the online behaviour of young people, as social media is an important platform for our project.

We realised we had much to learn! We used this opportunity to try out some new research methods alongside more traditional methodologies that could help us develop insights on these issues, to understand how to support 15-30-year-old Cambodians to engage in civic life, all through media and our programming.

How we responded to our research challenge

We conducted a face-to-face, nationally representative survey, to understand the youth media information ecosystem and civic engagement and to generate a national picture of the issues.

We followed up the survey with some qualitative work, conducted face to face and online. For this study we talked to young people and other stakeholders – including parents and community gatekeepers - to contextualise and validate the quantitative data.

Our research tools were carefully attuned to the context and sensitivities about discussing these issues. We moved any questions that might be sensitive to the back of the survey, and we used role-storming and projective techniques in the focus group discussions to encourage people to speak up.

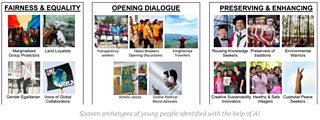

We commissioned a study to help us understand young people’s digital information ecosystems, using an artificial intelligence (AI) machine learning semiotics study (the Discover AI platform and Accelerate Drivers model) with more than 100 online sources to identify different youth archetypes. There were two dominant groups that emerged – ‘transparency seekers’ and ‘political micro-activists'. We felt that these groups were more likely to talk and discuss these sensitive issues, so we conducted more qualitative research with these groups to understand what they care about, and how they engage and behave with information online.

We also wanted to understand marginalised people, including those identifying as LGBTQI+, young people with disabilities, and people with limited access to the internet such as indigenous groups. To reach these people during COVID-19, when face-to-face research was difficult, we set up a number of online community discussion groups through Facebook chat, and telephone interviews and remote focus group discussions using Zoom - meeting people virtually in the way that they felt most comfortable.

How did we analyse and share the data?

We used data immersion and analysis workshops to reflect, analyse, triangulate and validate the data, before developing our reporting on emerging insights and trends.

Our research showed that young Cambodians have significant differences in their interests, capacity, and attitudes to civic engagement, and face different barriers. For this reason, a segmentation analysis – a process of dividing people into groups based on their similarities – was used to identify different groups of young Cambodians, based on their attitudes, actions, and discussion linked to civic participation and engagement. We used the survey data to split people into five segments with distinct media and communication needs, ranging from those who are disengaged and do not feel it is their place to be involved, to those who are actively participating in civic life.

Understanding the demographic composition of each segment – gender, sexual orientation, disability, location and so on – helped us to define each group’s communication needs, and so to support civic engagement.

How have the research insights been used?

The research insights contributed significantly to the framing and development of a project proposal for work on youth civic engagement, supported the development of the project Theory of Change, and are now being used by 麻豆约拍 Media Action’s project and production teams to support the design of media and communication outputs which are tailored to different target audiences.

For example, our new TV drama series “” has been designed to reach and engage young people from the ‘disadvantaged’, ‘unbothered’ and ‘motivated’ groups identified by the segmentation analysis. Our qualitative research has helped to provide rich detail on the lives and experiences of young people in Cambodia, so that storylines and characters in the drama reflect the reality of young people’s lives and frame content on civic engagement in a sensitive but engaging way.

We organized two virtual dissemination workshops to share and discuss the key research findings, and shared short summaries of key insights and data presented in infographics – useful to others in the sector, including NGOs and media partners, particularly during COVID-19 lockdowns.

What have we learned and what next?

As a researcher, it has been good to see how instrumental the research has been in informing the project approach, and how insights from the research have been used by the project and production teams. We have learned from trying new methods, and have been able to share this learning with other research teams in 麻豆约拍 Media Action.

Now our focus is turning to the evaluation of the project. Again, we are looking at what new and innovative approaches we can try, such as a/b testing of our digital media content to understand what works best in engaging youth audiences on social media, and online experimental research to test the impact of our digital content. We don’t want to stand still!

I’m also very proud that our efforts have been recognised by the ESOMAR Foundation. It is encouraging to see our work recognised internationally.

---

麻豆约拍 Media Action's work in Cambodia has been awarded a Making A Difference Award by the , presented during the in Toronto, 18-21 September 2022.

Learn more about our work in Cambodia - Sok San Family and Klahan9

Read the research summaries:

- Understanding how young Cambodians (15-30 year olds) use media and information

-

For more information, please contact Sao Vichheka, Research Manager, 麻豆约拍 Media Action Cambodia on sao.vichheka@kh.bbcmediaaction.org

Cities tend to forget the very people who are their lifeline.

The 12.5 million denizens of Bengaluru, known as India’s Silicon Valley, generate 5,757 metric tonnes of solid waste per day.

But the city’s estimated 30,000 informal waste pickers, who form the backbone of Bengaluru’s waste management system, are invisible and ignored. They live in deplorable conditions with low and unstable incomes, face significant workplace hazards, and are treated with suspicion and contempt.

Funded by the H&M Foundation, Saamuhika Shakti (SaaS, the Collective Impact Initiative), aims to address this situation. 麻豆约拍 Media Action, an initiative programme partner, turned to social media to create our Pathway to Respect, Identity, Dignity and Empowerment (PRIDE) project for informal waste pickers.

An informal waste picker who featured in our #Invaluables campaign

Lack of recognition

The PRIDE project’s formative research revealed that there is a lack of recognition of the humans behind the process of waste management. While people in the city see waste on the streets, and they are concerned about it, they failed to list waste pickers as important to their lives. On further probing, we found that while people appreciated the work of formal waste collectors, who are hired by the municipality for door-to-door garbage collection, informal waste pickers were still stigmatised. More than half of our study respondents said that informal waste pickers are dirty and shouldn’t be allowed inside residential building complexes.

Street rag-pickers look scary, so we don't go near them!

- Female, 39, housewife, Bengaluru

The pandemic strengthened these negative perceptions. Waste pickers, in turn, confirmed having to regularly deal with discrimination.

’They (the public) scold us. They feel they will catch the disease (COVID-19) from us. They think we have the virus. So, I do not like to go to work.’’

- Female waste picker, under 18

Research was used to identify segments within social media users among the general population of Bengaluru, based on their attitudes towards informal waste pickers. Our research and analysis showed three broad segments of people:

- Appreciators, who valued the role and contributions of informal waste pickers and understood their circumstances

- Sympathisers, who displayed an overall sentimentality towards informal waste pickers accompanied by stereotyping of their work

- Stigmatisers, who wanted to distance themselves from the waste picking community and displayed extremely negative attitudes

The project decided to focus on appreciators and sympathisers, who were more likely to become early adopters of any changes in attitude or behaviour.

Strategic reframing

In a country with a history of caste-based occupations and discrimination, bringing a change in mindsets is uphill work. The project turned to Professor Judith Butler to understand why some lives are valued and others not, and how marginalisation is contingent on rendering social groups virtually invisible.

Based on the reading of Butler and formative research, the project’s Theory of Change focused on the need to end the invisibility of informal waste pickers if their lives and work were to be properly valued. This involved a reframing of the work of waste pickers as involving special skills and productive labour essential for the city’s survival, as well as recognition of the fragility of social media users’ own lives in the face of environmental hazards. The recognition of this shared fragility is a pathway to creating a social bond that obliges us to care for each other. Establishing the interconnectedness between the lives of social media users and the work of waste pickers was integral to the former valuing the life and work of the latter.

Designing for PRIDE

The project used social media to connect the people of Bengaluru with informal waste pickers, by positioning the waste pickers as ’invaluable friends’, friends they did not know they had. The creative strategy was designed to lift the shroud of invisibility and open the eyes of Bengalureans to the value that informal waste pickers bring to their lives - as professionals, as humans, and as residents living side-by-side in the same city.

A explored the concept of friendship and revealed how informal waste pickers share the values normally associated with true friendships. The social experiment was conducted by Radhika Narayan, a popular actor and social media influencer. The film ended with a call to action to join a moderated private community on Facebook called the #Invaluables Facebook group.

Participants in our #Invaluables social media experiment were asked who their dearest friends were - then shown how informal waste pickers fit the description. /麻豆约拍 Media Action India

The content posted on this group brought Bengalureans closer to the waste picking community, by creating awareness and demonstrating the value of their work to save the city from being buried under a mountain of garbage, and therefore demonstrating their interconnectedness.

Crafting this journey of perception change required a steady stream of relevant content through the week, seizing every opportunity and fact in a strategic manner and converting it into engaging content that would bring this interconnectedness to life. We built the social media strategy carefully, weaving in the use of influencers wherever necessary and taking the conversations beyond social media to discussions on FM radio during regular shows, hosted by prominent city RJs.

The branding, Invaluables, was designed to strengthen the idea of ‘interconnectedness’. The brand identity uses image, colour and text to combine three graphic ideas – the joining of two hands, the use of two eco-friendly colours - blue and green - and the skyline symbolising the city of Bengaluru.

Analysis and impact

Social media statistics show that the first phase of the #Invaluables content reached at least 2.6 million unique people, 21% of the city’s population, with a total of 4.4 million video views and 509,429 engagements (e.g. likes, comments).

The first round of impact evaluation also shows that we have started to shift people’s understanding of waste pickers. There was an improvement in spontaneous awareness of different segments of informal waste pickers, from 10% at baseline to 16% among those exposed to the #Invaluables content. There was no such change within the control group. Analysis also shows greater discussion about informal waste pickers, their work and place in society among those exposed (60%) to the content, compared to those not exposed (49%).

We have demonstrated that an evidence-based, insight-driven, carefully crafted social media campaign can help shift negative perceptions attached to certain occupations and help reduce inequalities. With significant positive shifts in awareness and discussions about informal waste pickers after the first phase of the campaign, we are now confident in taking forward the idea of Invaluables to the next phase of building understanding and appreciation for the critical importance of their work.

Our next phase will demonstrate the connection between the people of Bengaluru and the city’s waste pickers - and why everyone should be aware of and celebrate a Happy Number.

Check out the Happy Number to learn more.

--

Varinder Kaur Gambhir is director of research, Soma Katiyar is executive creative director and Ragini Pasricha is director of content strategy at 麻豆约拍 Media Action India.

Learn more about our Invaluables project here: /mediaaction/where-we-work/asia/india/invaluables/

Read our press release about the Happy Number here: /mediaaction/where-we-work/asia/india/happy-number-invaluables/

The Invaluables project is part of the Saamuhika Shakti (collective impact) initiative, funded by the H&M Foundation.

Displaced young Syrians wait to receive humanitarian aid. Credit: Getty Images

The fourth commitment which humanitarian agencies sign up to under the states that ‘Communities and people affected by crisis know their rights and entitlements, have access to information and participate in decisions which affect them’. But for humanitarian practitioners, particularly those working in settings where humanitarian access is limited, sharing relevant, accurate information and ensuring communities’ needs and priorities are heard and acted upon can be easier said than done.

Research currently being conducted by 麻豆约拍 Media Action to inform a new capacity strengthening project funded by USAID Bureau of Humanitarian Affairs, is finding that humanitarian practitioners in the project’s three focus countries (Nigeria, Somalia and Ukraine) face various challenges communicating with communities affected by crises.

In Somalia, humanitarian practitioners we spoke to are facing challenges getting hold of accurate and relevant information themselves to be able to answer people’s questions, as communication and coordination between local and humanitarian organisations is a challenge. In Northern Nigeria, having capacity to communicate in the right languages to reach internally displaced people who often don’t speak the same language as the host community (see ). And in Ukraine, a recent in May 2022 identified getting information to people with limited access to digital platforms, as a critical challenge. Across the board, humanitarian practitioners feel their organisations have mechanisms in place to collect feedback from communities, but often these mechanisms are not known about, or not trusted by community members, and are therefore underused, especially by those who are illiterate, have limited access to mobile phones, or live in more remote areas.

Media practitioners we spoke to as part of the research said they face challenges getting access to information which is useful and relevant to their audiences, especially finding contacts within humanitarian organisations who are ready to answer audiences’ questions on air. Some also expressed frustration that they feel they are treated with suspicion by humanitarian organisations, or are contacted to distribute organisations’ press releases rather than create engaging and useful content for audiences. The research so far has found limited interaction between media and humanitarian practitioners in the project’s focus areas.

And these communication challenges are reflected at community level. A carried out by Ground Truth Solutions with recipients of cash and voucher programmes in Somalia found that 45% of respondents feel informed about available aid; and only 25% of respondents feel aid providers take their opinions into account when designing programmes. Community leaders within IDP camps we spoke to in Somalia felt that although they frequently communicate their communities’ needs to organisations during assessments, this information is rarely listened to and acted upon. A similar (2021), found that 48% of respondents do not know what aid is available to them, and 49% feel their opinions are taken into account by humanitarian staff. The found that 66% of participants say they need information about how to register for humanitarian assistance.

People gather to receive humanitarian aid in Sudan. Credit: Getty Images

麻豆约拍 Media Action has extensive experience supporting humanitarian and media practitioners to communicate more effectively with communities affected by crisis. Most recently, in Bangladesh, where 麻豆约拍 Media Action and have been training practitioners responding to the Rohingya Refugee Crisis under the ‘Common Service for community engagement and accountability’ project since 2017, we have found that trainees place a particular value on training and tools to help them communicate in Rohingya language. In a recent evaluation of the project, practitioners emphasised how training has helped them prioritize and develop communication and listening skills, which managers say has led to better community satisfaction.

“We were not sufficiently sensitive to the Rohingya community culture and there were also language barriers. Their perception of different issues were not clear to us. After getting training, staff have changed their methods, how they behave and talk to the communities.’’ Humanitarian practitioner, Cox’s Bazar Bangladesh

Where possible, 麻豆约拍 Media Action’s approach is to train humanitarian and media practitioners together, building the understanding that both have a critical role to play in ensuring communities have access to information they need. As have also shown, a recent study with participants of 麻豆约拍 Media Action’s ‘Lifeline training’ in Afghanistan found that the training helped bridge the gap and build understanding and connections between journalists and field practitioners, which they have been able to use in their work.

“The training has changed our relationship with media and journalists. By communicating with social workers and journalists, most of our communication problems are solved. Additionally, the training has increased our capacity in communicating with people in the communities.” Community health worker, Helmand province, Afghanistan

Over the next year, 麻豆约拍 Media Action will be working with humanitarian and media practitioners in Nigeria, Somalia and Ukraine to support them to overcome challenges they are facing to communicate effectively with communities affected by crisis in these countries. Learning from the project will be shared and disseminated at country and global level.

Nicola Bailey is senior research manager for Asia/Europe at 麻豆约拍 Media Action, based in London. Co-authors are: 麻豆约拍 Media Action's Hodan Ibrahim, senior research officer, Somalia; Mohamed Yonis, project director, Somalia; Anu Njamah, head of research, Nigeria and Cian Ginley Ibbotson, project manager, Ukraine.

Read more about our humanitarian response on our website.

Tea Cup Diaries recording of customers at tea shop in Myanmar

Within a stone’s throw of Sule Pagoda – one of Myanmar’s oldest and most sacred Buddhist sites – stands a Catholic church, a Hindu temple and a mosque. Worshippers rub shoulders in the nearby streets lined with crumbling colonial homes, Chinese new-builds and the hawkers who sell their wares off the potholed, sun-soaked pavements.

Yet the multi-religious diversity in downtown Yangon masks Myanmar’s darker relationship with religion.

Even when I first moved to Myanmar as a journalist for a local newspaper in 2008, the military regime recognised the media’s power to not only reflect society as it is, but to promote the society they desired. Late on a Saturday evening, we’d sit in the paper’s office, printing presses at the ready, drinking warm Mandalay beer, playing cards and waiting for the cuts from the Press Scrutiny Board (PSB), under the Ministry of Information. Everything from hip hop songs to books had to undergo censorship, and articles that challenged the idea of Myanmar as a homogenous Buddhist society were often the first to go, despite the fact that a significant minority of Myanmar’s 134 ethnic groups are Christian, Muslim or Hindu.

Opening - and intolerance

Later, as the military began its ‘roadmap to democracy’, telephone SIM cards went from US$2000 a pop to US$1; websites were unblocked and private internet companies were finally allowed access to the market, introducing many of Myanmar’s 54 million citizens to the internet for the first time. But alongside this opening came hate speech, fuelling further religious intolerance, particularly towards Muslims.

Even as laws were rewritten and civil society began to flourish, politicians and military actors used distrust of Muslims as a political tool to mobilise fear and sow division. Taxis, shops and offices sported the '969' supposedly ‘Buddhist’ movement, whose tenets include: Do not buy things from a Muslim shop. Do not be friends with a Muslim. Do not marry a Muslim. New laws were introduced to forbid a Buddhist woman from marrying a man from another religion.

In the midst of this, 麻豆约拍 Media Action – which set up its office in the country in 2013 - launched the Tea Cup Diaries, a drama designed to encourage religious and ethnic inclusion. While Facebook was being mobilised to spread hate speech and vitriol against the Rohinyga, a Muslim minority, the Tea Cup Diaries used the most-listened-to radio in the country to reach the Bamar Buddhist majority with stories about people from different religions facing the daily trials of life – trying to earn a living, struggling to care for their children and falling in love.

Tea Cup Diaries recording wedding of the character Aye Aye.

Lessons learned

We continued to navigate this difficult space through the official military ‘operation’ in August 2017 against the Muslim Rohingya people, which forced almost 725,000 people to flee to neighbouring Bangladesh. We built on the trust we had already established with our audiences to continue our storylines.

In February 2021, the military claimed back the power it had tentatively started to share, leaving many of the people of Myanmar at war with their own military and Tea Cup Diaries came off air, though it is still active on Facebook.

Over the years, Tea Cup Diaries promoted religious and social inclusion within a space where the very concept of national identity and unity is fiercely contested.

Here are five lessons we learned for communication practitioners working on religious and social inclusion.

1. Focus on what unifies people

Our research told us people’s biggest challenges were economic worries, fear of unemployment and financial insecurity – regardless of ethnicity or religion. This helped shape the drama’s premise, which charts a family struggling with the issues audiences face every day —money, livelihoods, and their family’s future. By drawing on common fears, hopes and dreams as the bedrock for the narrative, audiences saw people of different backgrounds facing similar dilemmas, reminding them of how they share common experiences. The lead characters were a Bamar Buddhist couple, in line with the intended audience, but other main characters were from a diverse range of backgrounds.

2. Understand the religious context

When we dug into what people thought about other ethnic and religious groups and how they interacted, we discovered people often lived ‘side by side, but not together’.

Not many people had casual friendships with people from different religious or ethnic backgrounds and where people did interact, it usually happened outside the home, in local tea shops, at work and, for young people, at school. This meant many people did not have the opportunity to understand what different religions practice and believe, which made them vulnerable to widespread misinformation and hate speech. This helped shape the story of the drama, which charts a couple starting their own tea shop on the outskirts of Yangon—a place where a diverse range of characters would realistically mingle, interact, and chat.

Our research also told us there was a perceived hierarchy of religions—especially among the Bamar Buddhist majority. They felt Hinduism was most similar to Buddhism. They related less to Christians, and felt they had least in common with Muslims. They did not feel Rohingya Muslims were even part of the country.

Our drama therefore approached different religions differently. To challenge misunderstandings about Christian beliefs, James, the young tea shop waiter, was a central character over several years. The audience watched him grow up, get baptised, go to Bible camp and sing hymns at Christmas. Our introduction to Muslim characters was more gradual. They initially featured as secondary characters, becoming more central as the audience warmed to them.

3. Use formats that invite audiences to step into another’s shoes

When James, the young tea shop waiter, knelt in his church, the audience were able to hear him praying. For some in our audience it was the first time they’d been given the opportunity to understand Christianity from what it might sound like inside a believer’s head. As one woman from Labutta described in : ‘I got to know that they (Christians) pray to their God, Jesus, in difficult times. It’s mostly the same as what I do when I get sad; I pray and count beads.’

Dramas and soap operas are particularly powerful at inviting audiences to step into another person’s perspective. Research suggests that when audiences are immersed in a fictional narrative, they often experience attitude and belief change in line with those expressed in the story (Green, 2021; Nabi & Green, 2015). Given the sensitive nature of religious and social inclusion, drama offered our audiences an opportunity to understand people from different backgrounds - not just through theoretical knowledge, but by getting to know their struggles, desires and fears up close and personal.

4. Use feedback from audiences to shape production decisions – particularly around highly contested themes

Given the sensitive nature of some of the issues, and the changing socio-political landscape – including the Rohingya crisis in August 2017, continued armed clashes between ethnic groups, increasing levels of fake news and misinformation fuelling ethnic and religious tension - it was important to keep abreast of how audiences were engaging with Tea Cup Diaries.

Every two to three weeks, audience panels helped our production team understand how audiences were reacting to and engaging with the drama, so they could adapt quickly to emerging trends. In particular, they helped us understand how far we could press different inter-ethnic and inter-religious relationships. For example, our audience grew fond of a storyline involving a romantic relationship between Sam (a Karen Christian man) and Htet Htet (a Bamar Buddhist woman). But a friendship between Inn Gine (a Buddhist woman) and Naing Gyi (a Muslim man) did not develop into a romantic relationship, as it was clear from the audience panel that this would not yet be acceptable.

5. Deeply engage your audience

Attitudes towards different religions are often deep-rooted and take a long time to shift. But, while research participants had mixed views on storylines with inter-ethnic and inter-religious friendships and relationships, our survey analysis found the more engaged people were with the programme, the more likely they were to accept such relationships, compared to those who do not listen. Listeners who were more engaged with the drama were 1.6 times more likely to discuss issues relating to ethnic and religious tension, compared to less engaged listeners. Listeners who were highly engaged were 1.9 times more likely than non-listeners to demonstrate higher levels of acceptance towards inter-ethnic and inter-religious relationships. And people who were 1.6 times more likely to have higher levels of knowledge about religions other than their own compared to non-listeners.

In a context as fractured as Myanmar, where the media is all too often a tool for sowing distrust and division, the Tea Cup Diaries drew on that most traditional of Buddhist qualities – compassion – and in so doing, opened up space for greater tolerance and understanding.

Becky Palmstrom lived and worked in Myanmar from 2008-2009 and again from 2011-2015. She was part of the Rohingya refugee response in Bangladesh, 2016/2017 and is currently a senior advisor on governance and rights for 麻豆约拍 Media Action.

This blog draws heavily on by Sally Gowland, Anna Colquhoun, Muk Yin Haung Nyoi & Van Sui Thawng (leads to third-party site)

麻豆约拍 Media Action is committed to highlighting and celebrating religious diversity and inclusion in our programming and our ways of working.

How many of us ever think about what happens after we flush?

Yet it’s an issue that concerns governments, sanitation experts, urban planners and public health specialists around the world - particularly in India, where 60% of urban India is not connected to modern sewage systems and relies on on-site sanitation such as septic tanks and leaching pits. This makes faecal sludge management (FSM) a pressing but hidden public health issue.

That’s why five years ago, Madhu Krishna, then deputy director of WASH and communities at the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation India, gave 麻豆约拍 Media Action this challenge:

“Could you make faecal sludge management an issue that is as important to people in urban India as air pollution has become? Could you get people to care about what happens after they pull the flush?”

Few homes in India's urban areas are connected to municipal sewerage, making waste management a major health issue. Credit: 麻豆约拍 Media Action

Since the launch of the ambitious Swachh Bharat Mission (Clean India Mission) in October 2014, India has made huge leaps forward in building toilets and eradicating open defecation. But faecal sludge management - or what happens to poo after you flush, how it is contained, when to empty the tank and where it ends up - was not getting as much thought as it deserves.

An invisible problem

Our research showed that the predominant attitude among our audiences was to flush and forget about faecal sludge, or avoid the problem for as long and by any means possible – including by building enormous septic tanks that do not need cleaning in their lifetimes. As one man from Trichy in the southern state of Tamil Nadu told us: ‘’I have built a big tank so that we don’t have to clean in frequent intervals. Why should I empty the tank if there is still so much space?”

According to a 2019 WaterAid report, adequate facilities and services for the collection, transportation, treatment and disposal of faecal sludge do not exist in most Indian cities. Private operators – often using illegal, manual methods – may even dump faecal sludge in drains, waterways, and on land. This untreated sewage contributes to high levels of diarrhoeal disease, which is responsible for more than one in 10 infant deaths in India. Faecal sludge is the largest polluter of ground water in urban India.

Our mandate was clear: how do we first make faecal sludge a problem you cannot ignore? How do we make the invisible, visible?

Our campaign #FlushKeBaad illustrated the sanitation value chain so that people could understand what happens after flushing. Credit: 麻豆约拍 Media Action

Combining the art of drama with behavioural science

We examined our audience’s attitudes towards desludging, and the type of containment system they own, to help us identify three audience segments: proactive desludgers (22%), reactive desludgers (the majority – 66%), and connected to drains (11%).

We knew people weren’t making ‘optimal’ decisions when it came to sanitation and septic tanks. In fact, they departed from what traditional economic theory would classify as ‘perfect’ rationality in specific and predictable ways. For example, many focused on the short-term gains (e.g. not paying for regular desludging), and ignored both the long-term benefits (e.g. protecting water resources and ensuring the well-being of families and communities) and uncertain future costs (e.g. repairs or system failure).

Behavioural economists call this ‘present bias’. We needed to reach these ‘procrastinators’ as well as those who hadn’t thought about what happens after they flush. We also set out to frame the link between faecal sludge disposal and health as a positive gain, because we know people's choices are heavily influenced by inertia and avoiding losses.

We wanted to increase awareness about correct FSM practices – regular desludging, building the right kind of septic tank and asking where your poo is being dumped - and to heighten the sense of risk.

The drama focused on two triggers or framing effects – risk perception and social disapproval - which would make urban populations take either individual or collective action to bring about change.

Why drama?

Everyone likes a good story – particularly in India with its rich oral history and huge film and television industry. Working with national broadcasters gives drama unparalleled reach and scale. And we know drama works - it can be an incredibly powerful force for positive social impact.

But we don’t mean ANY drama. We mean locally produced, culturally relevant dramas that are developed using behavioural insights and informed by communication theory. These dramas are tested with audiences before they go to air, to ensure they deliver on engagement, entertainment and communication objectives.

Evidence demonstrates these carefully crafted narratives - sometimes called edutainment or drama for development - not only inform, educate and entertain. They can also prompt , influence and challenge , intent to act and .

Drama can be particularly effective because it engages people on an emotional level, unpacking complex issues and making them easier to understand, so they stick in people’s minds. Role-modelling positive behaviours over time can change mindsets – even around deep-seated behaviours and norms.